Parasitic nematodes are a large group of wormlike organisms that can infect an astonishing array of plants, insects, and animals, including humans. They undergo dramatic changes when they come into contact with their host’s tissues, releasing proteins toxic to the host, leading to tissue damage or even death. Because parasitic nematodes are a major source of human disease and mortality, infecting nearly 25% of the global population, scientists have extensively studied the kinds of toxins they produce.

A new study led by the University of California, Riverside suggests that some of what scientists have learned about nematode toxin production and release may be missing the mark because it came from research done on nematodes outside of a host. To better understand nematode proteins the authors call for more research on nematodes inside living hosts or in conditions that better mimic infection.

Because it is hard to identify nematode proteins inside the host’s tissues, most researchers induce nematode protein secretion in a petri dish or test tube, with the assumption that they are the same as what the nematode produces when in contact with the host.

Rather than try to extract the toxic proteins from the host tissue, a team led by UC Riverside’s Adler Dillman, an assistant professor of nematology, and Dennis Chang, a doctoral student in Dillman’s lab, examined the RNA transcriptome of two types of nematodes that infect and kill insects.

The transcriptome is the set of all RNA molecules in the nematode. RNA “transcribes” blueprints encoded in DNA and builds proteins according to their instructions. By looking at the RNA in action, the group identified protein-making instructions while the nematode was inside the insect.

They discovered that the nematodes can produce different proteins when inside the host than when induced in the petri dish.

“Our findings highlight the importance of testing assumptions experimentally and may lead to the discovery of new tissue-damaging or immunomodulatory proteins that were overlooked or missed in previous research,” Dillman said. “The fact that many proteins secreted by insect-parasitic nematodes are also found in nematode parasites of mammals suggests that some key features of parasitism are shared among distantly related parasites.”

A better understanding of the mechanisms and types of proteins nematodes secrete could lead to improved treatments or preventatives for nematode infections in people and animals.

Dillman, however, plans to use toxins from the insect-infecting nematodes in a pesticide, or to genetically modify crops to produce the protein, making them naturally insect-resistant. Most corn and cotton in the U.S., for example, has been genetically modified to produce a protein called BT toxin, originally found in a type of bacteria. But insects are starting to resist BT toxin, and the nematode-derived toxin could serve as a supplement or alternative. Dillman recently received a grant from the UC Riverside’s Office of Research and Economic Development to develop this technology.

The paper, “A core set of venom proteins is released by entomopathogenic nematodes in the genus Steinernema,” is published in PLoS Pathogens. In addition to Dillman and Chang authors include UC Irvine doctoral student Lorrayne Serra, UC Riverside postdoctoral scholar Dihong Lu, and Ali Mortazavi, an associate professor of developmental and cell biology at UC Irvine.

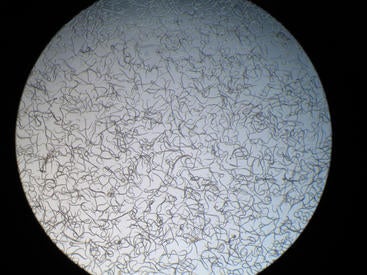

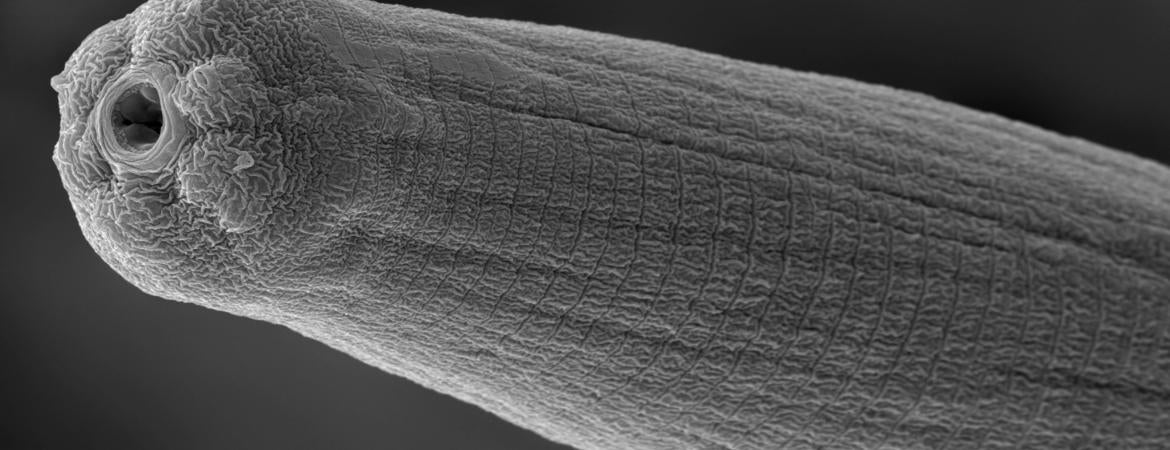

Header photo: An activated Steinernema carpocapsae nematode. (Adler Dillman/UCR)