By the turn of the 20th century, tuberculosis rates across much of the U.S. were in steady decline. But in some communities, the struggle to fight the deadly disease had only just begun.

These communities included the 29 tribes of Southern California’s Mission Indian Agency — Cahuilla, Chemehuevi, Cupeño, Kumeyaay, Luiseño, and Serrano bands among them.

In the wake of mass development, members of the tribes had been weakened by the destruction of many of their indigenous food sources, said Clifford Trafzer, a distinguished professor of history and Rupert Costo Chair in American Indian Affairs at the University of California, Riverside. This made them particularly susceptible to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, measles, whooping cough, and influenza.

For three decades, Trafzer has studied the health of Mission Indian Agency tribes, as well as how collaborative efforts between tribes and a new breed of public health advocate — the traveling field nurse — tempered rates of infectious diseases and improved health outcomes for American Indians.

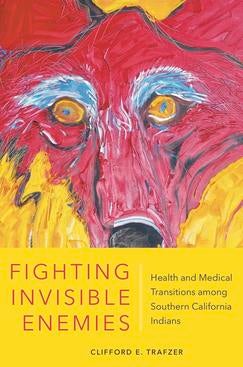

In his latest book, “Fighting Invisible Enemies: Health and Medical Transitions Among Southern California Indians,” released this month by the University of Oklahoma Press, Trafzer chronicles the work of field nurses who served in the region between 1928 and 1948.

At the national level, the public health nursing corps was established in 1922, with the first field nurses appointed to work on reservations in South Dakota and New Mexico. Nurses worked closely with American Indian families, whose mothers and grandmothers served as important conduits of knowledge related to health, personal hygiene, and child care.

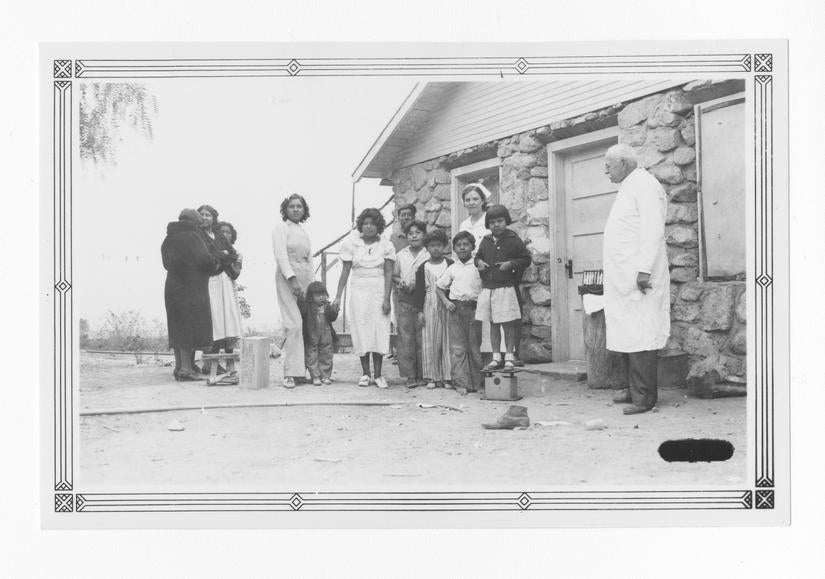

The first field nurse assigned to the Mission Indian Agency, Florence McClintock, arrived in the region in 1928, serving American Indians living in San Bernardino, Riverside, and northern San Diego counties.

Families within the Mission Indian Agency had been hit especially hard by infectious diseases, with tuberculosis emerging as the primary killer of American Indian men, women, and children in Southern California in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Several factors threatened tribal communities’ health, including diminished food supplies and tribal members’ proximity to natural hot springs. Living near the springs, Trafzer said, put American Indians at risk for interacting with already-infected “health seekers” who had sought out the spas in the hopes the mineral water would cure their tuberculosis.

Because of this, much of the nurses’ work involved spreading awareness about how to counter the disease, namely by isolating those infected. American Indians supported the effort, allowing field nurses into their homes, letting nurses examine their children and recommend treatments, and reading pamphlets on how to control disease.

“Some acted on a nurse’s requests to screen windows, doors, and outhouses,” Trafzer wrote. “Indian families became more conscious of how and where bacteria thrived and how to destroy invisible enemies by using soap, water, and disinfectants.”

Meanwhile, nurses also administered to students at Riverside’s Sherman Institute, one of 25 off-reservation boarding schools established nationwide to assimilate American Indian youth. Caring for and educating students at schools like Sherman Institute was an important aspect of field nurses’ work, as students carried health-related information back to their families when they returned to reservations.

“This is a good example of people working together for a common goal: better health,” Trafzer said. “The field nurses are heroes to me because of the relationships they created through their work; over time, they became very close to the people they worked with, including other ‘indigenous nurses’ who shared knowledge about the medicine ways of their people, such as plant medicine.”

For much of his research, Trafzer turned to the National Archives and Records Administration, whose Pacific Region Federal Records Center is in the Riverside County city of Perris. The center is a major source of American Indian records, he said, including birth, death, and other medical records.

“Back when I first started researching these topics, I happened upon a pretty extensive report and realized it was a monthly report by a field nurse,” he said. I didn’t know what a field nurse was at the time, but I started investigating and found the material to be very compelling. These nurses were in everybody’s homes and would describe everything from what each reservation and home looked like to how many people were sleeping in a room together.”

Trafzer also traveled to local reservations to gather the oral histories of tribal elders — mainly women, he said, who shared both indigenous knowledge and fond memories of the tough-as-nails nurses who had served their families with compassion decades ago.

At its core, Trafzer said the book is a testament to the strength of women who put aside their differences and triumphed over disease — even without the assistance of streptomycin, the only effective antibiotic known to kill tuberculosis.

“A lot of the early field nurses had previously been World War I nurses, so they had seen battle and the gore of war,” he said. “They were up for the challenge and the adventure of living out in the middle of nowhere with only a used automobile to get them from place to place.”

Looking at death data from the period, Trafzer said it’s easy to see the significant impact field nurses had on lowering tuberculosis rates among American Indians in the region. However, the “positive era” of public health nursing wouldn’t last; by the late 1940s and ’50s, conservative lawmakers had cut funding for the nursing corps as part of its termination policy.

Also eliminated as part of the federal government’s termination efforts were the Mission Indian Agency’s Soboba Indian Hospital, located in San Jacinto, and the use of contract physicians who treated American Indian families.

“People were left to fend for themselves,” Trafzer said. “It took years, but by the 1970s, Indians in the region were using federal funding to create and manage their own health centers. That kind of self-determination is very representative of Southern California Indians — people deciding for themselves and acting.”

“Fighting Invisible Enemies: Health and Medical Transitions Among Southern California Indians” was made possible by a $50,400 grant awarded to Trafzer in 2016 by the National Endowment for the Humanities.