When Victoria Reyes has a rare moment of free time, she likes to read about unsolved mysteries. Things like cruise ship disappearances, which can be especially hard to investigate when they happen in international waters.

Cruise ships are just one example of what Reyes, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of California, Riverside, calls “global borderlands.” These places are foreign-controlled places and often geared toward international exchange; they’re also legally ambiguous, existing in a sort of gray area when it comes to the laws that govern them.

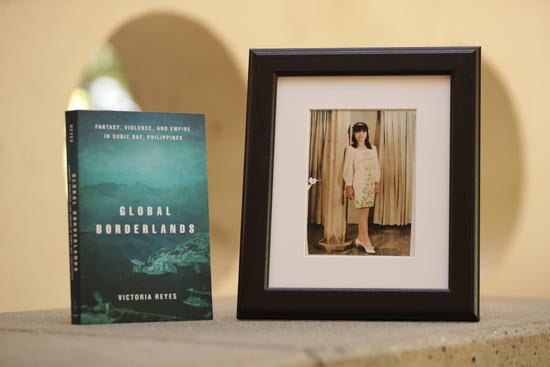

Overseas military bases, special economic zones, tourist resorts, international branches of university campuses, and embassies are all types of global borderlands, according to Reyes. She explores a combination of two of these — an overseas military base turned special economic zone — in her debut book, “Global Borderlands: Fantasy, Violence, and Empire in Subic Bay, Philippines,” released this week by Stanford University Press.

Across six chapters, readers are introduced to a broad range of real-life characters who have called the Philippine bay home. What results is a sprawling account of the push-and-pull nature of power, viewed through the lens of Subic Bay and its transformation from a U.S. naval base in the early 1900s through 1992, to the tax- and duty-free Subic Bay Freeport Zone.

Among those characters are the government officials who architected the agreements establishing the military base and freeport zone; the Filipino workers employed there; and victims and perpetrators of violent crime in the region. Reyes also pays close attention to Filipina sex workers and “marriage migrants,” U.S. servicemen, and the Amerasian children many of them fathered on the heels of the Vietnam War.

The stories of marriage migrants are especially personal for Reyes. Her maternal grandmother grew up in the same neighborhood as the U.S. Subic Bay Naval Base, had a daughter with one U.S. serviceman — he later died by suicide — and married another.

Her grandmother’s marriage “offered a whirlwind of global travel … and an immediate departure from the land she longed to disappear from, allowing her to fulfill her dream of changing her life,” Reyes wrote. Still, it was “a relatively short time before her fairy-tale story started to show cracks,” and the couple divorced when Reyes’ grandmother was around 30.

Ultimately, she landed in Ohio, where she worked as a domestic worker, at a fast-food restaurant, and at a steakhouse while raising five children and her first granddaughter — Reyes — whom her eldest daughter gave birth to at 15.

A mystery emerges

As she grew up, Reyes found her grandmother’s nostalgia for the naval base — seemingly a symbol of military power and hegemony — puzzling. Yet her grandmother spoke fondly of the base, which at its height was one of the largest U.S. overseas military bases in the world.

During the same era, the U.S. military was the Philippines’ second-largest employer, “pumping an estimated $500 million each year into the Philippine economy,” according to Reyes. Like many global borderlands, the base — and now the freeport zone that replaced it — came to represent opportunity and “the good life” to Filipinos just as much as it did imperialism.

“I’ve always been deeply inspired by my grandmother’s migration story,” Reyes said. “It really sparked my sociological imagination and interest in the multiplicity of experiences and getting away from binary thinking. The purpose of sociology isn’t to go into a situation with a particular point of view and collect information that confirms it; the point is to really try to understand what’s going on.”

Through her research, Reyes said she’s come to realize that while it’s impossible to deny the influence of colonialism in Subic Bay, it’s also unfair to deny the strides made by Filipinos to get and hold onto power in their interactions with Americans.

“I think it’s really dangerous to gloss over the agency of Filipinos themselves — in some circumstances, it can be a little patronizing,” she added. “Social life is complex, and dichotomous thinking doesn’t really reflect what’s going on in a place like Subic Bay.”

The bay remains a popular port for foreign ships, and, along with the freeport zone, houses a tiger zoo, a water park, tourist resorts, universities, an international high school, shipping and manufacturing facilities, an upscale mall, and three gated residential communities.

The U.S. military, meanwhile, regained a physical footing in the Philippines in 2014 with the passage of the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, which allows U.S. troops to occupy select locations throughout the Southeast Asian country for extended periods.

Unequal footing

To get a grasp on life in Subic Bay, Reyes lived there for nine months in 2012-13, during which she interviewed locals. She also performed archival research, such as examining international treaties, tax documents, and more than 429 legal cases — some involving murder.

A notable example is the case of Jennifer Laude, a 26-year-old transgender Filipina who was killed in 2014 by a U.S. Marine. Laude’s murder ignited debates about who, exactly, should take custody of American military personnel arrested for violent crimes in Subic Bay — U.S. or Philippine law enforcement agencies? Reading the cases, Reyes said, emphasized the legal uncertainty of global borderlands like Subic Bay.

“We tend to think most things are guided by a rule of law, and that different countries are containers of sorts with their own sets of laws, but in fact, law in itself is really complex,” she added. “There are these ambiguous spaces that aren’t necessarily governed by a single country’s rule of law, and they become the critical sites where global tensions arise.”

Laude, a sex worker, was part of a long Subic Bay legacy.

The sex industry flourished in Olongapo, the city surrounding the naval base, during the Vietnam War, Reyes wrote. Using a framework she calls “the heroic love myth,” Reyes found that Filipina women viewed and pursued American men as “saviors” who would lift them out of poverty and provide access to a new life in the U.S. through marriage.

While the myth came true for some women, it didn’t for many others. Thousands of Filipina women were left with children of Filipina and American descent, many of whom still aren’t recognized by their biological fathers or the U.S. government.

In the Philippines alone, there are an estimated 30,000-52,000 such children, Reyes noted, who often face discrimination among Filipinos because “having an American father, in the mind of many, means that their mother was a sex worker.”

Families — however fragmented — can tell us a lot about the dynamics of the world at large, and their stories shouldn’t be discounted, Reyes said.

“Inequality is built into the foundation of a place like Subic Bay,” she added. “We need to understand the dynamics of global borderlands in order to understand how global inequality is perpetuated and reproduced.”