Climate change is accomplishing what centuries of exploration could not: opening the fabled Northwest Passage, a maritime shortcut from Europe to Asia via the Arctic Ocean.

Research led by the University of California, Riverside, could help ships navigating these freshly thawed routes avoid the Titanic’s fate with a new way to forecast the motion of floating ice.

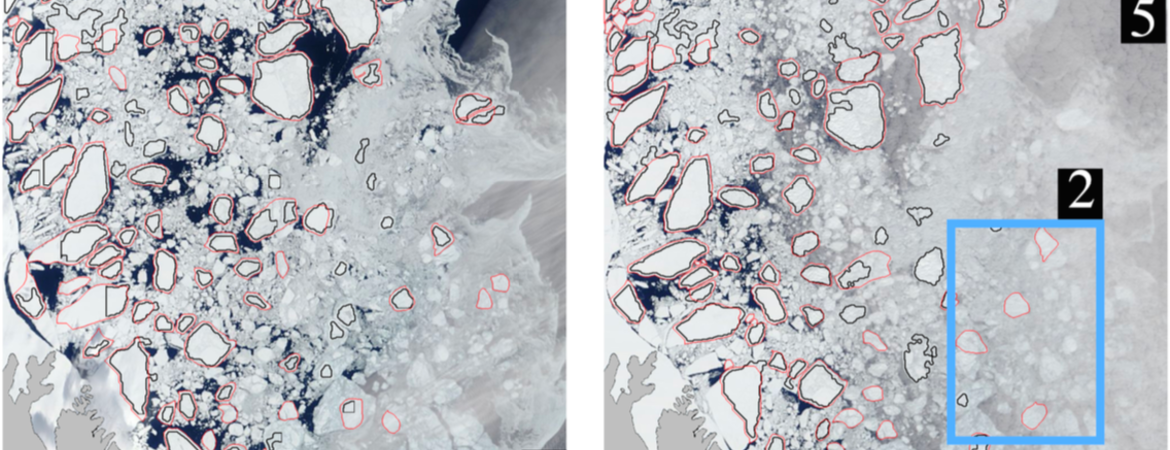

A group led by Monica Martinez Wilhelmus, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering in the Marlan and Rosemary Bourns College of Engineering, is the first to use moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer, or MODIS, satellite imagery to understand long-term ocean movements from sea ice dynamics.

MODIS sensors aboard NASA satellites have been collecting daily images of arctic ice floes — large, flat sheets of floating ice — for over 20 years, but using them to study how they move with ocean currents has been a laborious task. Clouds often obstruct the view and floes must be identified and marked by hand.

The engineers used image-processing algorithms to remove clouds, sharpen details, and separate individual floes. They then used image analysis algorithms to map the movement of floes over a period of days. The resulting ocean current maps were about as accurate as maps made using more labor-intensive traditional methods. Tracking sea ice will help scientists better understand the sources driving sea ice transport.

“No one had bothered before to use MODIS because the satellite is sensitive to clouds and it’s hard to identify ice,” Martinez said. “Our algorithm automatically filters clouds and uses other image processing algorithms that give the velocity and trajectory of the ice floes.”

The analysis will help researchers quantify how the interactions between ocean currents, climate, and sea ice have changed in the last two decades. This will ultimately improve ocean models, which for the most part, do not resolve at the scales necessary to study these interactions.

“MODIS data is one of the longest records of earth ever compiled,” said first author Rosalinda Lopez, a graduate student in Martinez’s lab. “This means that we are able to expand our analysis to almost two decades to observe the variability of sea ice as dramatic changes transform the region.”

The rate at which ice spreads apart affects how fast it melts. Ice that rapidly spreads away from other ice melts more quickly than ice that stays close together, similar to how a handful of ice cubes in a glass of water will melt more slowly than a handful of ice cubes in a bathtub.

This affects how fast and how much fresh water from the ice blends into the salty sea water, which in turn affects how the ocean current moves.

“Adding fresh water to the sea water affects its energetics, which affects the current,” Martinez said. “We need to understand how ice interacts with the ocean.”

With the Arctic melting faster than ever, it’s important to learn how ocean currents are changing. Ocean currents are intimately associated with the climate, and a better understanding of long-term currents will help improve models of climate change.

“This is a new field,” Martinez said. “No one knows how the ice is going to behave.”

The altered currents will also affect Arctic communities that depend on hunting and fishing. As their economies falter, ships will need to find safe ways to deliver supplies to help them survive. Proposed oil drilling in the Arctic could also mean oil spills, and the UC Riverside technique could help predict how oil slicks would behave.

The paper, “Ice Floe Tracker: An algorithm to automatically retrieve Lagrangian trajectories via feature matching from moderate-resolution visual imagery,” is published in the journal Remote Sensing of Environment. In addition to Martinez and Lopez, the paper was co-authored by Michael Schodlok, a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.