New research from UC Riverside shows scientists may soon be able to prevent disease-spreading mosquitoes from maturing. Using the same gene-altering techniques, they may also be able help boost reproduction in beneficial bumblebees.

The research shows that, contrary to previous scientific belief, a hormone required for sexual maturity in insects cannot travel across a mass of cells separating the blood from the brain — unless it is aided by a transporter protein molecule.

“Before this finding, there had been a longstanding assumption that steroid hormones pass freely through the blood-brain barrier,” said Naoki Yamanaka, an assistant professor of entomology at UCR, who led the research. “We have shown that’s not so.”

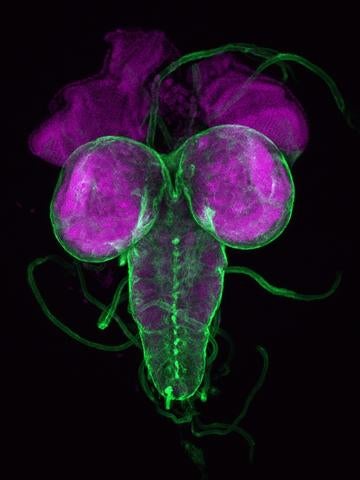

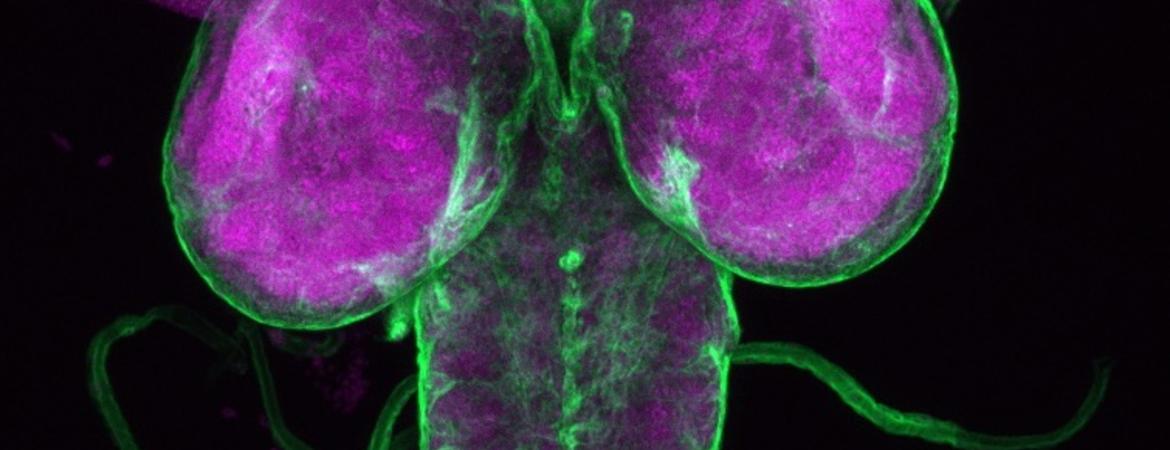

The study, published this month in the journal Current Biology, details the effects on sexual maturity in fruit flies when the transporter protein is blocked.

Blocking the transporter not only prevented the steroid from entering the brain, it also permanently altered the flies’ behavior. When flies are in their infancy or “maggot” stage, they usually stay on or in a source of food.

Later, as they prepare to enter a more adult phase of life, they exhibit “wandering behavior,” in which they come out of their food to find a place to shed their outer body layer and transform into an adult fly.

When the transporter gene was blocked, Yamanaka said the flies entered a median stage between infancy and adulthood, but never wandered out of their food, and died slowly afterward without ever reaching adulthood or reproducing.

“Our biggest motivation for this study was to challenge the prevailing assumption about free movement of steroids past the blood-brain barrier, by using fruit flies as a model species,” Yamanaka said. “In the long run, we’re interested in controlling the function of steroid hormone transporters to manipulate insect and potentially human behaviors.”

Currently, Yamanaka is examining whether altering genes in mosquitoes could have a similar effect. Since mosquitoes are vectors for numerous diseases, including Zika, West Nile Virus, malaria and Dengue fever, there is great potential for the findings to improve human health.

Conversely, there may be a way to alter the genes to manipulate reproduction in beneficial insects as well, in order to help them. Bumblebees, whose populations have been declining in recent years, pollinate many favorite human food crops.

Also, there is the potential for this work to more directly impact humans. Steroid hormones affect a variety of behaviors and reactions in the human body. For example, the human body under stress makes a steroid hormone called cortisol. It enters the brain so humans can cope with the stressful situation.

However, when chronic stress is experienced, cortisol can build up in the brain and cause multiple issues. “If the same machinery exists for cortisol in humans, we may be able to block the transporter in the blood-brain barrier to protect our brain from chronic stress,” Yamanaka said.

“It’s an exciting finding,” said Yamanaka. “It was just in flies, but more than 70% of human disease-related genes have equivalents in flies, so there is a good chance this holds true for humans too.”