LGBTQ youth make up at least 40% of all young people experiencing homelessness in the United States — an outsize portion, considering LGBTQ youth comprise only around 5%-8% of the total population of young Americans.

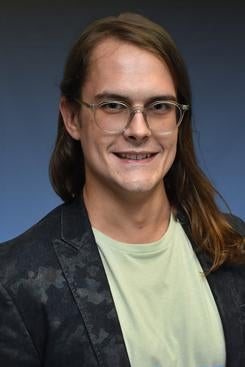

Until now, their experiences have gone mostly undocumented, according to Brandon Andrew Robinson, an assistant professor in the gender and sexuality studies department at the University of California, Riverside. Robinson uses the pronouns they/them/their.

Robinson’s research explores how various social inequalities intersect with and impact contemporary LGBTQ communities, as well as how those inequalities are exacerbated when elements like race, ethnicity, and class are added to the mix.

Beginning in 2015, Robinson spent nearly a year and a half observing and interviewing LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness in central Texas.

“When I decided I specifically wanted to research LGBTQ youth homelessness, it was around the time when issues like gay marriage and whether to allow LGBTQ people in the military were largely dominating conversations within LGBTQ politics and movements,” Robinson said.

“But at the same time, numbers were coming out that showed LGBTQ youth disproportionately make up the population of youth experiencing homelessness,” they added. “These youth were being mostly ignored, and I wanted to know what their experience of homelessness looks like since they’re largely the future of the LGBTQ community.”

In an article published this week in the journal Gender & Society, Robinson examines a particularly consequential aspect of LGBTQ youth homelessness: frequent interactions with police, and a far too common result of those interactions, incarceration.

The U.S. is home to more incarcerated people than any other country in the world, accounting for nearly 25% of the world’s total prison population, Robinson noted. Less frequently discussed, however, is how practices of policing and incarceration nationwide perpetuate the marginalization and subjugation of LGBTQ people.

Robinson’s research builds on the work of civil rights lawyer and legal scholar Michelle Alexander. Published in 2010, Alexander’s book “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness” argues current practices of hyperincarceration have undermined the gains of the civil rights movement for many black and brown people, particularly those who are poor.

Robinson’s work takes Alexander’s field-shifting research a few steps further by shining a spotlight on issues related to gender and sexuality as they intersect with race and class.

Just like the population of youth experiencing homelessness, LGBTQ people disproportionately make up America’s incarcerated population, Robinson said. Likewise, LGBTQ individuals comprise around 15% of all youth in juvenile detention centers.

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual people are also three times more likely than the general population to experience incarceration. That rate increases for transgender people, one in six of whom has experienced incarceration, and dramatically skyrockets for black transgender people — half of whom will experience incarceration in their lifetime.

For youth experiencing homelessness, who often spend substantial amounts of time on the street, coming into contact with police is almost a certainty.

Through their regular interactions with police and other agents of the state, LGBTQ youth — and LGBTQ youth of color, in particular — are criminalized, Robinson wrote, with their gender expressions, LGBTQ identities, and sex lives branded as deviant.

Beginning in 2015, Robinson conducted 40 in-depth interviews at shelters and a drop-in center with LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness whose ages ranged from 13-25.

They observed several patterns: First, 36 of the 40 respondents reported interactions with police, while 31 reported being arrested or held in jail or prison.

Some transgender and gender-expansive youth of color recalled being subjected to “trans profiling,” or having police assume they were participating in sex work and stopping, ticketing, or even arresting them as a result.

Others described discriminatory treatment such as harassment and humiliation, being put in the wrong gender-segregated jail cells and prisons, and being placed in solitary confinement.

“These practices aim to uphold the gender binary as well as heteronormativity in the public sphere,” Robinson wrote. “These practices also privilege middle-class people, white people, and/or men — including middle-class, white LGBTQ people — who often find more safety in the public sphere.”

Robinson said the wrong conclusion to draw from their research is that LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness are engaging in criminal behaviors that warrant police attention or punishment.

“The institutions are what criminalize these youth, not that they’re engaging in criminal behaviors,” Robinson added. “We know this because plenty of people engage in the same behaviors, but the police only target certain youth.”

Moreover, their research underscores the fact that even in a supposedly “modern” era that’s seen major advancements in LGBTQ rights, many of those protections haven’t been extended to all LGBTQ people, including the youth whose experiences Robinson chronicled.

The discrimination faced by those youth from police and other agents of the state may be more difficult to combat because it’s more insidious, primarily targets poor people of color, and is sometimes bolstered by dominant, white, middle-class LGBTQ values.

But in Robinson’s view, dismantling systems that perpetuate the discrimination is necessary for real change to happen.

“The combination of policing, criminalization, and prison is a main apparatus of the state that continues the marginalization and subjugation of LGBTQ people, especially LGBTQ people of color,” they added. “If we care about LGBTQ equality and we’re fighting for LGBTQ rights, then we need to grapple with and tackle the prison-industrial complex since it’s a main institution that’s actually marginalizing LGBTQ people.”