For Juliette Levy, teaching online has been a part of daily life since 2012.

Levy is an associate professor of history at the University of California, Riverside, where her research focuses on modern Latin American economic and financial history. An expert in digital pedagogy, she was among the earliest University of California professors to make one of her courses available online across campuses. Today, she’s moved all of her lower-division undergraduate courses online, and she continues to experiment with digital tools such as web-based learning games and virtual reality.

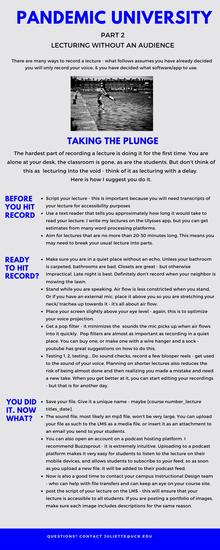

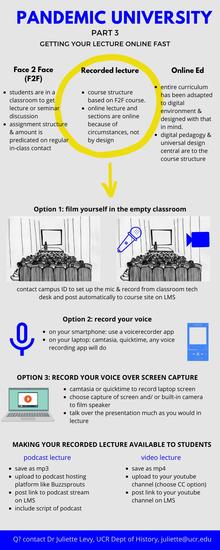

As the spread of coronavirus has driven more and more colleges and universities online, Levy has turned to Twitter. Her online-education best practices for educators and students alike can now be found in a series of infographic guides she’s titled “Pandemic University” — but that’s not all she had to say about navigating the transition to online learning.

Where does your interest in online learning stem from? I’ve always been interested in what good things can come from technology, but from a consumer angle — how does it make life easier? I’m not an evangelist, but I tend to think that while transitions are difficult, there’s always a new balance we achieve from change. When it comes to education, I saw students bringing laptops and cellphones to class, and rather than banning them, I gave them something to do with them.

What do you think this moment in time is revealing about the current state of online education in the U.S.? Most research campuses have been slowing trying to educate faculty about online tools and online instruction, but this is an entirely different medium — faculty have to change both how they teach and how they assess. What’s obvious now is that there’s an enormous lag between training people and having enough people ready to do this kind of instruction.

Are there any benefits to online learning that might become more apparent during this time? There are enormous advantages to both teaching and learning online. The first is accessibility: We can teach under any circumstances. Education is definitely bumping up against some problems when it comes to space and scale, and I think technology can help us solve many of those problems. We don’t need a classroom, we don’t need to travel to and from class — and neither do our students. They don’t need to drive to campus, they don’t need to put their children in daycare to go to class. If a student has any type of disability, an online class can often be more ADA-compliant than a face-to-face class. In terms of access, I don’t think you can beat an online class.

Another plus is that when you’re teaching online, you’re also teaching digital literacy. We want to teach students things they can’t just pick up in books, and teaching them how to interact online by modeling behavior that isn’t toxic, but helpful and collaborative, is so valuable. In this age of endless clickbait and deep-fake media, we can also teach them how to question what they read online and seek out reliable sources. That’s a huge advantage of a well-structured online class: Everyone becomes a better digital citizen.

Do you have any advice for faculty members as they transition to teaching online? Part of what we faculty need to remember is that this isn’t an equivalence; we can’t just replicate our classes online. It’s a learning curve, and everyone is going to have to just take it one step at a time. If you can manage to get everyone on Zoom for your first class, that’s an achievement. It’s important to temper your expectations, be kind to yourself, and be kind to your students. And ask your students for help — this is a situation where they might know more than you do. It’s a great exercise in democratic classrooms.

All this isn’t to say that face-to-face interaction isn’t valuable, or that the community we create on campus isn’t an enormous part of the university experience. But that’s not going to be possible for a while, and in the absence of that, we have this medium that’s extremely conducive to communication and to community. The only way we’re going to maintain community through this crisis is by seeing each other online. These are undeniable upsides we shouldn’t ignore even after this situation abates.

What about practical recommendations for those who are teaching online for the first time? My recommendation would be to create podcasts and upload them to an external hosting system, or do videos and upload them to YouTube, then link to those on our campus learning management system, or LMS; otherwise, my fear is the LMS will be completely overloaded. I’d urge people to record their voice and provide a portfolio of the images or slides that they’d normally talk over in a lecture. There are a few reasons why; first, an audio file is much ‘lighter’ to upload and easier to access on a mobile device. More students have access to a smartphone than a laptop, and more families have multiple smartphones as opposed to multiple computers or laptops.

Additionally, a podcast can be much longer than a video lecture. With a video, you can only expect someone to watch about 25 minutes on a screen, but people listen to podcasts for much longer. You can upload them to a podcast-hosting platform that’s free or almost free, and students can subscribe to the feed and listen on their phones. It’s sort of a win-win in terms of saving our campus LMS by not overburdening it and providing students with access to your lecture material without binding them to a computer for an hour to listen to you talk.

How do you respond to some professors’ fears that online education will eventually replace them? Those fears aren’t unique to pedagogy. The only way technology replaces us is if we can be automated. In reality, what happens in a class is a relationship — as instructors, we provide a certain amount of content in lectures and assigned readings, and then we provide context for that content by determining how we want students to apply it in assignments and exercises and discussion sections. Most of the learning occurs when students interact with the content in the context of assignments, and later when instructors give feedback. There’s no automation of that relationship, whether it’s face to face or online. If anything, a well-designed online platform geared toward education is going to make the teacher’s role even more relevant and central to a student’s education. But in order for faculty to believe this, they need to be able to trust that the university won’t hijack their course material, and that the technology doesn’t actually work without them.

As a result of the current situation, do you think we might see speedier advances in online education? This period highlights some of the holes we have in digital infrastructure on campuses. But the thing about online education is that it’s not just about infrastructure; it’s also about pedagogy. University administrations can decide to invest in digital infrastructure and really tool up on that side, but they also really need to provide funds for faculty to receive training in digital pedagogy. That’s the key part here.

Header image by Stan Lim; all infographics by Juliette Levy