The tragedy of heterosexuality isn’t that men are heterosexual. It’s that they’re not heterosexual enough.

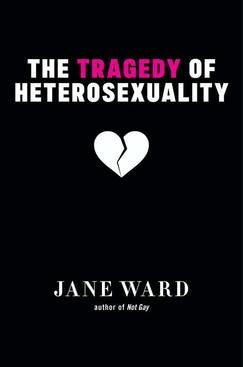

That’s according to UC Riverside professor of gender and sexuality studies Jane Ward, whose new book, “The Tragedy of Heterosexuality,” examines marriage manuals, self-help books, and “dating science” seminars, concluding that for over a century these products have tried, and failed, to solve the problem at the heart of heterosexuality: Men and women don’t like each other very much.

The dislike is not rooted in biological difference but patriarchal gender dynamics in which men gain prestige in the eyes of other men by having sex with women, whether the women receive pleasure or not. The assumed natural inevitability of heterosexual attraction, called heteronormativity, makes this uncomfortable and frustrating situation intolerable for both sexes. Men require sexually yielding female partners who make few demands of their emotions or time and women hate the demeaning, manipulative, even painful roles they must accept to make their relationships work.

“One of the ways that heteronormativity has survived is by convincing both gay people and straight people that being straight makes for a happier, healthier, easier life. This has made people fearful to explore queer desire by depicting gay life as tragic and difficult,” Ward said. “But more to the point of my book, it has masked over how much misery straight people —straight women, in particular — actually experience.”

Ward argues that if we take misogyny, violence against women, and the daily inequities of straight relationships at all seriously, we start to see that gendered suffering is a core part of many straight women’s —and men’s— experiences. We also start to see this kind of suffering is as tragic as the kinds produced by homophobia. The difference is that straight people are expected to be made wildly happy by the very relationships that actually cause them to be miserable.

“Straight culture promises women the world, but, in reality, offers women very little,” Ward said. “Queer culture, on the other hand, is a source of joy for most queer people; it’s homophobia and straight culture, not queer culture, that is the source of most queer suffering.”

Looking in on heterosexuality as a queer outsider and ally, Ward rejects the commercialized self-help tactics she examines and proposes a more radical approach, adapted from queer and feminist writers and personal conversations, which she calls “deep heterosexuality.” Straight couples don’t need to learn cleverer and more subtle ways to manipulate each other. They need to find ways to relate that don’t depend on patriarchy and misogyny.

Men need to learn to genuinely like women and situate loving and pleasing women at the center of their sexual attraction to women. Men can learn from lesbians how to desire and have sex with women and love them as true equals. They can identify with women, share women’s interests and concerns, and still find women as thrilling as lesbians do.

“From a lesbian feminist perspective, many straight men seem to have only a half-baked desire for women, a feeble version of what lesbians feel,” Ward said. “What I am arguing for is what I call deep heterosexuality, wherein straight men learn to like women so deeply that they actually like women. I am arguing for straightness to take its own impulses even deeper, to make them more authentic.”

How did it get to be this bad? Ward reviews popular marriage manuals from the 19th century onward and finds that marital rape and mutual revulsion at each other’s bodies contradicted the developing belief that a husband and wife should be loving companions. Books emphasized the innate aggression of male sexuality and women’s duty to submit.

Many of these books were written by white eugenicists concerned that this mutual antipathy would reduce the white birthrate and emphasized harmonious marriages and reproduction as a tool to maintain white supremacy.

Ward shows that misogyny, or men’s hatred of women, was an accepted fact of heterosexual relationships when the American self-help movement began in the early 20th century. The physicians, sexologists, and psychologists who were considered experts on heterosexual courtship and marriage took for granted that men’s first impulse toward women was disdain and even violence, and that husbands found their wives’ ideas, conversation, and emotional and sexual needs to be unimportant and irritating.

Though some of the language has changed over time, and some feminist ideas have crept in, Ward finds the same ideas repeated in contemporary, wildly successful self-help books such as John Gray’s “Men are from Mars; Women are from Venus” and in an array of self-improvement seminars.

In the popular consciousness, women and men are assumed to have totally different interests, personalities, and sex drives, making them inherently incompatible. Heterosexual relationships, thus, become a battleground where partners get what they want from each other through coercion and manipulation.

“Self-help books for straight couples in the 1980s and ’90s doubled down on the idea that the gap between women and men was innate and therefore unavoidable. The best men and women could do was learn a few tricks — or ‘skills’ — to get what they wanted from the opposite sex while minimizing conflict,” Ward said. “This same approach still persists today, as self-help books, webinars, dating coaches, marriage therapists, and a whole slew of what I call ‘hetero repair’ professionals teach straight couples to work around gender inequality, rather than undo it.”

But queer people have escaped this prison, Ward says, showing what straight people have to learn from queer relationships. This does not necessarily mean embracing common queer practices such as nonmonogamy, kink, or chosen families. It means straight people can learn to desire, objectify, satisfy, and respect their partners all at the same time, as well as have hot sex and equitable relationships in the way that most queer couples strive to do.

Men, Ward shows, have the most work to do in this regard.

“Psychologists have been arguing that men and women are fundamentally different, with different emotional and sexual interests, since the inception of the discipline of psychology. This approach, and the way it has been tethered to heterosexual romance, has gotten us nowhere,” Ward said. “It is possible to shift gears and imagine what it would be like if men thought of themselves not just as ‘sexually attracted’ to women, but powerfully oriented toward all women’s well-being and liberation. This will not only be good for straight women, but also tremendously healing for men.”