Over nearly eight decades, photographer Bruce Davidson has documented some of the most iconic moments in American history. “Lift Your Head: Bruce Davidson and the Evolution of Seeing,” a new exhibition at the California Museum of Photography, explores Davidson’s work and the role of documentary photography in shaping narratives both historically and in the present day. The exhibition, which will be available to view online at Virtual UCR ARTS Dec. 1, features roughly 100 photographs from a collection of work by Davidson anonymously donated to the California Museum of Photography in 2018 and showcases some of his best-known projects including, “Brooklyn Gang,” “Time of Change,” “East 100th Street,” and “Subway.”

Born in Oak Park, Illinois, Davidson, 86, began experimenting with photography at the age of 10, later studying photography at the Rochester Institute of Technology and Yale University before being drafted into the U.S. Army. Following his military service, he worked briefly as a freelance photographer before joining the renowned international photographic cooperative Magnum Photos in 1958. Davidson’s work has been widely exhibited and has appeared in numerous publications including LIFE, Time Magazine, Vogue, and The New York Times. Known for his humanist approach, Davidson has been welcomed into spaces where he was an outsider, capturing intimate images of communities with the goal of presenting his subjects authentically and without pretense.

“Bruce Davidson spent a lifetime working on being there for whomever or whatever he was photographing, rather than conforming the image to what he wanted to see,” said Sarah Bay Gachot, MA ’12, curator of the exhibition. “There’s a great honesty in his work that, to me, feels like it comes from the harmony between Davidson and his subject.”

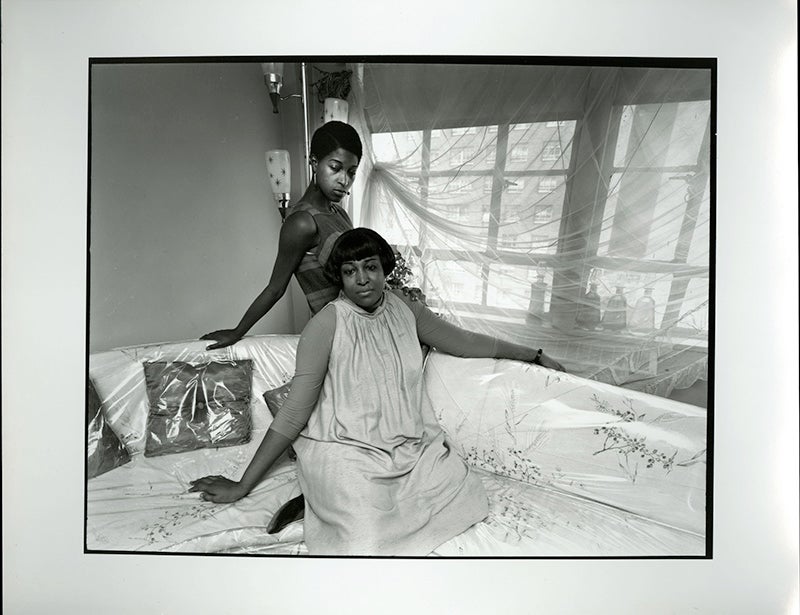

In his portraits of 1960s Harlem for his “East 100th Street” project, Davidson sought to photograph residents in a way that showed complexity rather than perpetuating its image as a crime-ridden and dangerous community. Among photographs of weddings and other portrayals of daily life, Davidson also helped residents document housing violations, and his images became a useful aid to the Metro North Citizens’ committee in its advocacy for urban renewal support.

“I think Davidson always felt that he was an outsider — even when he was growing up the son of a single mother outside of Chicago,” Gachot said. “Perhaps this was partly why he was drawn to intense and dedicated projects in which he would spend months or years getting to know a place or community. He was patient, observant, and respectful. In this way, he felt he could bridge his outsider status. He would often approach people and photograph them in the way they wanted to be seen as much as possible. The complexity here lies in the way the work was and is consumed.”

Gachot said Davidson’s work has evoked a variety of responses and interpretations, despite his attempts to present an objective view of the people, communities, and events he photographed. When “East 100th” was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, or MoMA, in New York in 1970, not far from the neighborhood portrayed, the question arose as to whether the exhibition did more to placate the consciences of the audiences at MoMA than advocate for those who lived on East 100th Street, she said. Davidson has also been hailed as the first photographer to document Harlem. But Gachot said many photographers of color came before Davidson and some see institutions’ focus on his work as representative of the erasure and racism that has perpetuated in the arts.

“When East 100th Street was shown at MoMA, one critic called the work demeaning to the residents of Harlem, another implied the masterful form complicated the politics behind the images, and still another saw the work as having transcendent and powerful aesthetics ‘usually reserved for the more privileged classes’ — a comment that is racist in itself,” Gachot said. “I think the important question now is how we proceed forward with our ears and eyes open to listen for the opposing views to come. Maybe there’s another way to think about what we see.”

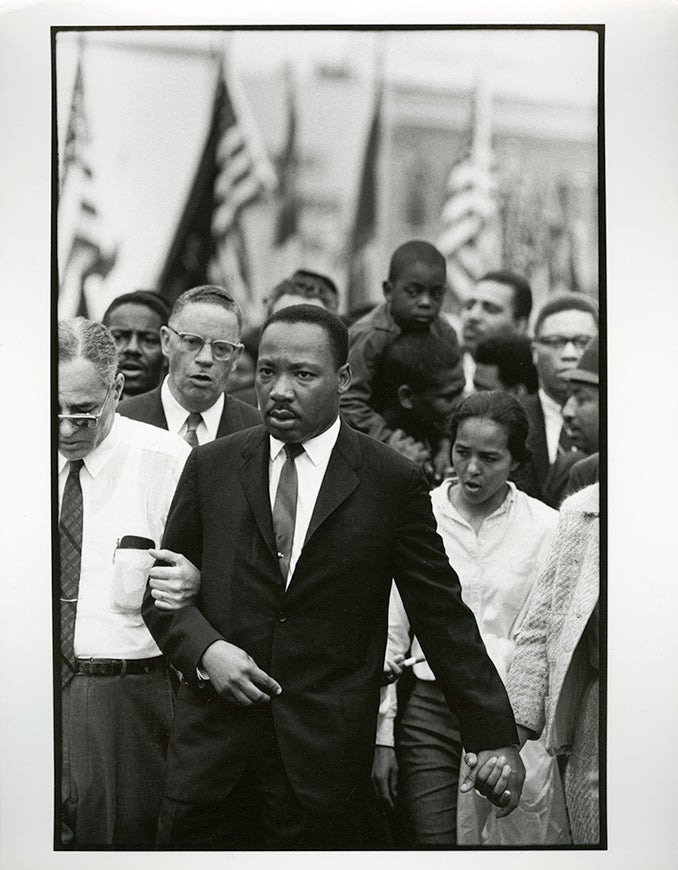

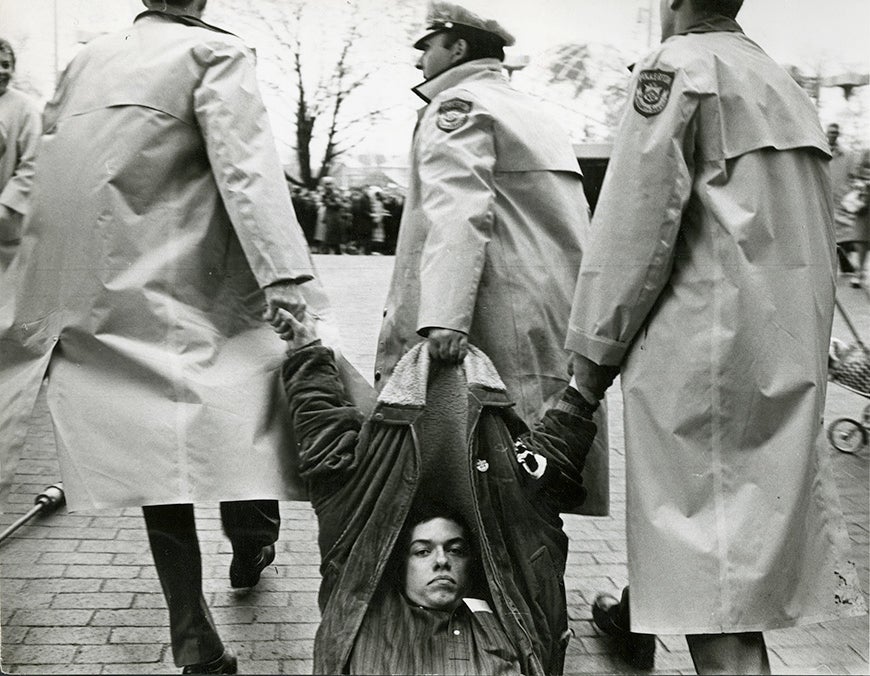

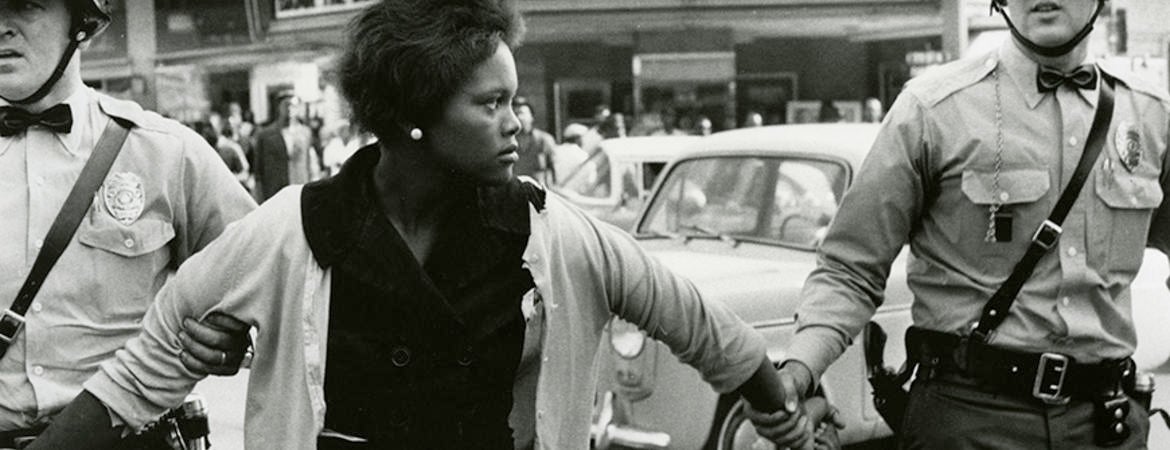

Davidson’s photography documenting important moments in the Civil Rights movement is especially resonant today against the current Black Lives Matter movement. The series “Time of Change” includes photographs of major historic events including the Freedom Riders in 1961, the March on Washington, D.C. in 1963, and the Selma March in Alabama in 1965, among scores of other demonstrations and protests across the South. Davidson also turned the lens toward Black life, capturing nuanced depictions of social environments during times of unrest.

“Davidson’s civil rights work has been an inspiration, both contemporaneously, when photojournalism was essential to educate people on the important organizing and protest that was taking place in the South and places like Chicago and New York, as well as today, as we see echoes of that passion and effort,” Gachot said.

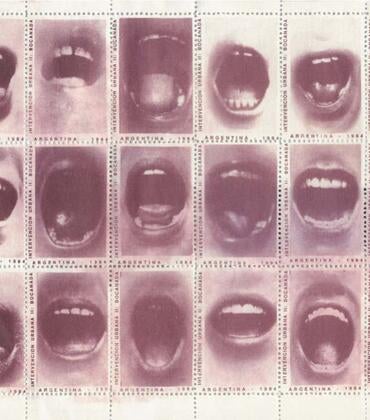

In presenting “Lift Your Head,” Gachot hopes viewers will consider what meaning can be found in these photographs in the context of today — whether they can impact the future or merely perpetuate ideas from the past, how much is subjective and how much is truth. She thinks it is also important to examine how documentary photography has evolved, now more widely accessible but further complicated by digital media, and how the way in which imagery is consumed can inform meaning.

“Since the inception of photography, it has been important to consider whose voice is behind the image,” Gachot said. “Who is telling the story? Especially when that story is meant to give a voice to the disenfranchised. We can look at these images and ask, what is included, and what might be missing from just beyond the frame?”

UCR ARTS Reopening Information

While Riverside County is currently in the first phase of reopening, UCR ARTS has been preparing to welcome back visitors to enjoy exhibitions in a safe environment when the county moves into phase three. As such, many new measures will be implemented in compliance with state guidelines surrounding COVID-19 and to ensure the safety of museum guests and staff.

Read more about UCR ARTS’ reopening plan and regulations below:

- UCR ARTS is scheduled to reopen when Riverside County moves into phase three, or the orange tier, of reopening. The county it currently in phase one, or the purple tier.

- Operating hours will be reduced during the first 90 days, with the museum open Thursday-Friday from 12-5 p.m. and Saturday-Sunday from 11 a.m.-5 p.m.

- Tickets can be purchased online or in person and are timed for entrance into the museum every 20 minutes. Advanced registration is strongly recommended.

- Groups are limited to no more than five; 90 people maximum are allowed in the museum at any time.

- Entrance into the museum will only be allowed through the Culver Center. Exiting will only take place through the California Museum of Photography.

- Anyone entering the museum will be required to wear a facemask that covers the nose and mouth. Face masks are available to guests for free if needed. Hand-sanitizing stations will be located on every floor of the museum. At this time, water fountains will not be available.

- Social distancing will be enforced with paths demarcating the correct route through the exhibitions. Signage will be placed throughout the museum to guide visitors and inform guests of protocols.

- Guests feeling unwell are asked to reschedule their visits. Tickets can be shifted to a later date by museum staff at no extra charge.

Find more information about UCR ARTS’ reopening and reserve tickets at ucrarts.ucr.edu. For guests who would like to experience UCR ARTS exhibitions online, including “Lift Your Head,” visit virtualucrarts.ucr.edu.

Header Image: Bruce Davidson, "Birmingham, Alabama," 1963, from the series "Time of Change," 1961-65. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos.