The news stories go like this: A gay or transgender teen rejected by their homophobic family is forced to survive on the streets. What the stories don’t describe is how poverty, along with schools, prisons, child protective services, and homeless shelters, push LGBTQ youth with fragile family ties onto the streets.

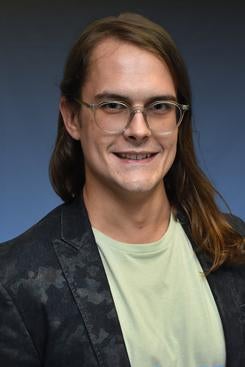

In “Coming Out to the Streets,” UC Riverside gender and sexuality studies professor Brandon Andrew Robinson shows that in a society where most institutions are organized to enforce or reward heterosexuality and a rigid male/female gender binary, LGBTQ youth must navigate barriers that push them to make up a disproportionately large portion of the youth homeless population. Family rejection, though important, is often only a step toward a painful series of interactions with other social institutions that make living on the streets the only way some LGBTQ youth can express their gender and sexual selves.

“The perceived path to homelessness for LGBTQ youth that emphasizes family rejection is often based on survey data, where youth or service providers tick a box,” Robinson said. “My research revealed that it is really family rejection within a context of poverty, racism, and instability. Social institutions that police gender and sexuality create violent spaces that push people out.”

LGBTQ youth make up about 40 percent of the youth homeless population, despite only being 5 to 8 percent of the total U.S. youth population. To understand this situation, Robinson volunteered at a youth drop-in center in Austin, Texas, and a LGBTQ shelter in San Antonio, Texas, for a year and a half and interviewed 40 LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness and 10 service providers.

The youth were mostly Black and Latina/o, and from poor or working-class families where economic precarity and racism destabilized family dynamics. To some families, it was important for children to embrace heterosexuality and conventional gender behaviors because these were seen as routes to respectability and economic security. If a parent rejected a youth’s queer or gender expansive behaviors, they often had few other family members to take them in and even fewer means of financial support.

As youth bounced between staying with family members and friends, switching schools frequently and often surviving abuse or committing acts criminalized as petty crimes, many eventually came to the attention of child protective services and/or the criminal legal systems, then ended up in foster homes or juvenile detention facilities. Children of color are more likely to be removed from their families or arrested than white children.

In both the foster care and prison systems, youth had to obey rules and follow routines meant to separate men and women, prevent sexual behavior, and enforce conformity to dominant gender and sexuality norms. For example, in prison and often in foster care, trans women were housed with and treated as men. Bathrooms also lacked privacy and left youth vulnerable to assault.

After “aging out” of the foster care system or being released from jail, the youth experienced homelessness. Or, as one youth put it, they “came out onto the streets.”

To survive on the streets, LGBTQ youth had to develop what Robinson calls “queer street smarts,” such as learning the locations of public gender-neutral or single-occupant bathrooms, avoiding sexual assault, or how to do sex work. They developed friendships with other LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness based on companionship, protection, and economic assistance. The trans women of color were often arrested for minor infractions, such as jaywalking, because police assumed they were sex workers.

The drop-in center and shelter offered respite from the streets: a safe place to shower and sleep, meals, medications, assistance with changing names and gender on identification cards, and help finding jobs. But they also had rules intended to train the youth into middle-class respectability. Strict curfews, for example, made it difficult for sex workers to find clients during the lucrative night hours. Frequent drug testing meant a youth could be denied entry to the shelter or permanently banned. Rules against sex and requirements to keep doors open made intimacy difficult for couples.

In these and other ways the shelters served as yet another institution that policed the gender and sexuality of the youth.

“The message to these impoverished, mostly Black and Latina/o youth was: It’s OK to be gay or trans, as long as you behave like white middle-class people,” said Robinson.

The result was that most of the youth cycled through living on the streets, in shelters, in prison, and with family or friends. Some minimum wage jobs allowed them to move into an apartment. These jobs were easy to lose and rents were high, putting them back into the cycle.

But to some, living on the streets was preferable to enduring the constant surveillance of shelters.

“When we hear people say they’d rather be on the streets because other places are too violent, we know there’s really a problem with how we’re trying to help LGBTQ youth who are experiencing homelessness,” said Robinson. “At the end of the day I just don’t think shelters work. We should be shifting funds into permanent housing, not shelters.”

Getting people into housing, whether or not they comply with rules or treatment, is one of the best ways to help LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness, concludes the book. Robinson writes that this approach, known as Housing First, costs less per person than homeless shelters and ends the shelter-street-prison cycle. Other recommendations include raising the minimum wage, installing more all-gender bathrooms, making it easy and free to change name and gender on identification cards, universal healthcare, and decriminalizing both sex work and homelessness.

“Police do not need to get involved in addressing homelessness,” Robinson writes. “We need to protect people experiencing homelessness from discrimination and violence, as many of the youth in this study experienced harassment and violence on the streets. A main protection would ensure housing for everyone. As a human right, getting someone experiencing homelessness into housing should not come with any barriers.”

Header photo: University of California Press