On Dec. 4, a federal judge restored the rights afforded undocumented immigrants eligible for the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA program.

The program was established within the Department of Homeland Security in 2012 to grant work permits and protection from deportation to young people brought to the United States without documentation when they were children.

DACA had been in a state of suspension since the Trump administration stopped accepting new applications in September 2017, which compelled a lawsuit from the University of California.

At UC Riverside there are about 550 undocumented students and nearly 4,000 in the UC system. Of those, approximately 1,700 are DACA recipients.

In the Dec. 4 ruling, U.S. District Judge Nicholas G. Garaufis ordered the Department of Homeland Security to post a public notice by Monday, Dec. 7, to accept first-time applications and ensure work permits are again valid for two years. Legal challenges to DACA from states continue, and advocates for the immigrants hope for congressional legislation to permanently affirm the rights of “dreamers.”

What does this all mean? UCR’s Jennifer Nájera, associate professor and chair of the Department of Ethnic Studies, provides an insight. Nájera’s research includes undocumented communities, DACA, immigration, and the Latinx education experience.

With the Dec. 4 ruling, are “dreamers” in the clear?

Fortunately, California offers broad protections and resources to undocumented young people, as does the UC system. DACA has been a wonderful program, we have seen benefits, especially economically. With a DACA permit students are able to work, which allows them to pay for school-related expenses, pay for transportation to and from school, as well as gives them greater food security. It also allows young people to work and to contribute to the economy in that way. For those undocumented young people in states without such protections, this ruling was a temporary reprieve. Since 2018, 10 states have filed federal lawsuits claiming DACA as unlawful, and there will be at least on more federal hearing challenging DACA’s legitimacy before the Biden inauguration.

What do you anticipate will happen to DACA when President-elect Joe Biden assumes office?

Joe Biden has said that immigration reform is one of his top priorities for his first 100 days in office, and many immigration rights groups will be holding him accountable to that.

What is the best-possible remedy for those in the DACA program?

Ultimately, offering DACA is not enough because it is a presidential executive order. If Biden is not reelected in four years, the DACA program and all of its beneficiaries will be vulnerable again. Comprehensive immigration reform that includes youth as well as their families would provide stability for individual immigrants, their families, and their communities. What we are seeing is that even those students with DACA have high levels of stress and anxiety because they live with the fear that their parents will be deported.

Many parents of DACA recipients have been here for decades, and they have made the U.S. their home. Offering a path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants — both children and adults — who meet certain criteria would be ideal.

What are the most important aspects of the Dec. 4 ruling in regards to DACA applicants?

New eligible DACA applicants can now submit their applications. The federal government stopped accepting new DACA applications in late 2017, which means there are increasing numbers of undocumented students with no federal legal protections in the UC system. Last week’s decision opens the possibility for new applicants to receive temporary work permits and a temporary reprieve from the fear of detention and deportation.

In July, the Department of Homeland Security issued a memo stating they were changing the DACA timeframe to one-year renewals instead of two. The Dec. 4 ruling reverses that policy and allows DACA renewals for up to two years again. This is important because now young people will pay the $495 renewal fee every two years instead of every year, which takes a lot of financial stress away from our students.

Are there national economic benefits to DACA?

Absolutely. The sole fact of being able to legally work is a huge benefit both to our students and society. In California alone, undocumented college students (both with and without DACA) come from different majors. In a recent study of UC and Cal State students we saw 35% studying in the social sciences, 29% STEM majors, 21% undeclared, and 15% studying in the arts and humanities. They are preparing to go to work as engineers, health care workers, lawyers, and social workers. These are young people who are contributing to various sectors of our economy. More than that, however, they are contributing to our society and are an integral part of our social fabric.

Can you provide a demographic insight into who these “dreamers” are?

In the UC system, we have a diverse representation of countries of origin. Most of them are from Mexico, but many students are also from Central and South America, Asia — particularly Korea and the Philippines, as well as Africa. Our students tend to have high GPAs, hold jobs, and most are civically and politically involved at levels much higher than the general population of young people.

Having said that, it’s also important to note that many undocumented young people are very careful to not paint themselves as exceptional, but rather as an extension of their families and their communities. Many credit their parents as being the “original dreamers.”

Related:

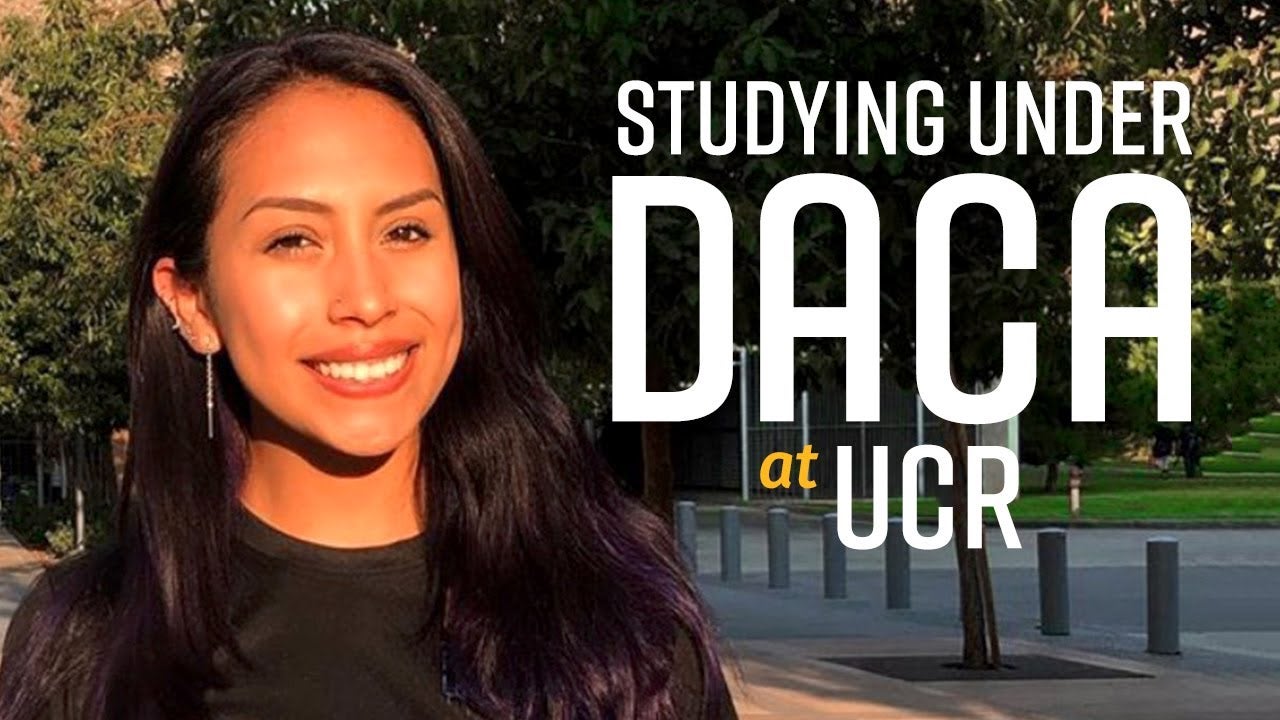

First-person account of a UCR DACA recipient, Sandra Ayllón. Read her personal essay and watch the video below: