Beginning around 1990, the demographic landscape of the Los Angeles area changed dramatically through an infusion of immigrants from Mexico and Central America. But historian Jorge Leal says its impact on the neighborhoods of the Los Angeles area has never been charted in earnest.

With his recently published research, Leal has taken a furtive step into documenting the Latinx community’s emerging L.A. footprint, using an unconventional source. If you want to know about the Latinx community’s presence in L.A. over the past 30 years, Leal says to follow the music posters.

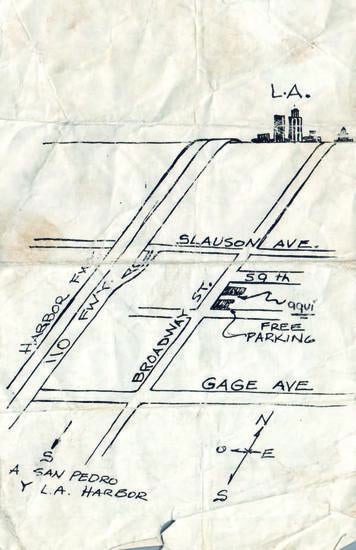

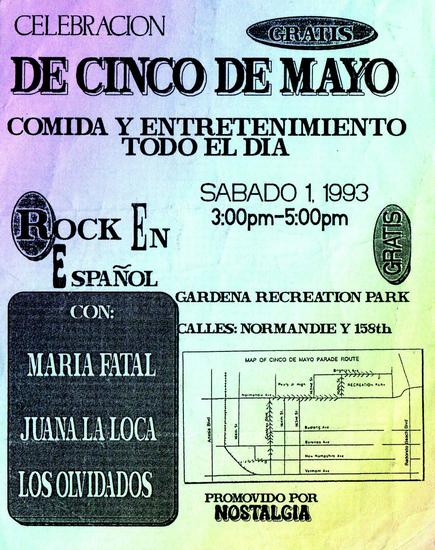

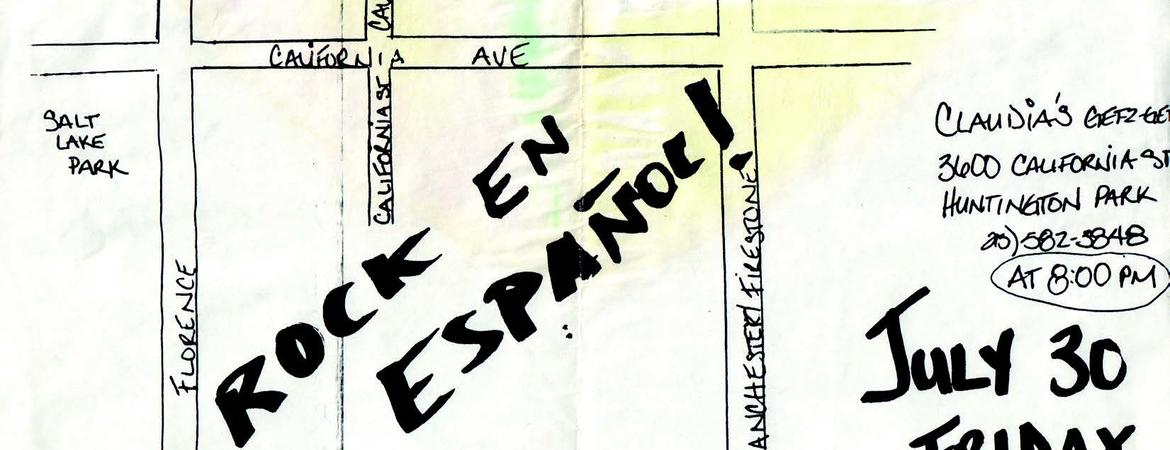

In the days preceding social media and broad Internet access, local music was promoted in L.A. and other urban areas via crude posters taped to store windows and tacked to utility poles. The L.A. music posters tell where the “Rock Angelino” music — and the Latinx community — could be found.

Leal says his publication and analysis of the music posters begins to tell the story historians have largely ignored — of the mid-late 20th century influx of Latin Americans into what he says were “formerly lily white” communities.

“My study is a first step to approaching the history of Latinx communities at the end of the 20th century,” said Leal, an assistant professor of history at UCR.

The immigration of Latin Americans coupled with the growth of the U.S.-born Latinx population to create majority or sizable populations in many areas beyond traditional Latinx Eastside neighborhoods, such as Boyle Heights. According to 2019 U.S. Census estimates, the 10 million residents of Los Angeles County today include 48% Latinx; 26% white; 15% Asian Americans, and 9% Black residents.

But Leal said Gateway Cities such as Huntington Park and South Gate in Southeast Los Angeles are yet misrepresented — with a depiction of their history as being primarily white, and/or monoracial— though Leal said these are ethnically diverse communities.

He said the swift demographic shift also led to “racial anxiety” among a white population that pushed for restrictive policies against immigrants and the city’s nonwhite citizens. This included federal housing policies that Leal said effectively segregated communities of color from white Los Angeles.

“Studying Southern California, and in particularly South and Southeast Los Angeles in the latter third of the 20th century with historical lenses is crucial to understand how the current conditions of the metropolitan area came to be after white flight,” Leal said. “These conditions created new and vibrant ethnically defined areas, such as the Latinx communities in Southeast Los Angeles where ingenuous strategies to housing scarcity, public space, and economic subsistence are created by Latinxs.”

The music fliers, which include neighborhood maps, offer insight into where the Latinx presence was, and where it was expanding. A sense of place is meaningful to any ethnic community, Leal said.

“But in particular for the Latinx community having a sense of place allows for a sense of belonging in the present and future within Southern California,” Leal said. “Plus, having a sense of place in the contemporary period anchors their presence to the multiracial past of Southern California, in which Latinxs — along with Indigenous, Black, and Asian Americans — have long been present.

“I argue that Latinxs, along with other people of color, have used mapping to proclaim their presence within the Los Angeles metropolis,” Leal wrote.

It’s not only the music posters that reveal the Latinx imprint on L.A., Leal said. The music itself, from bands such as Los Olvidados and Raskahuele, also offers cartographical insight into places that held and hold meaning to the Latinx community.

“These lyrics also share insights on how Latinxs used the streets and freeways to expand their agency,” wrote Leal, who is the curator of The Rock Archivo LÁ, an online repository of ephemera from Latinx youth culture.

Leal said Rock Angelino “offers detailed lyrical cartographies about sites that are pivotal to the immigrant Latinx experience of this time period, which expanded beyond the confines of the traditional ethnic Mexican neighborhoods of East Los Angeles.”

The music often depicts the workaday struggles and weekend “releases” of workers in the L.A. Latinx community, many of whom were employed in labor-intensive, temporary jobs.

“I have spent all week working like a slave,” asserts the Los Olvidados song “Viernes,” or “Friday.” The popular Raskahuele song “Alvarado Street” discusses feeling a sense of belonging to L.A., but not having full legal status.

The music’s geographic references sometimes spring from the popular practice of weeknight car cruising along Southeast thoroughfares such as Whittier Boulevard and Soto Street. Leal borrows loosely from Chicano writer Alex Espinoza — a UCR graduate and the Tomás Rivera Endowed Chair of Creative Writing at UCR — in writing: “Cruising… is not about where you are going, but rather cruising for ethnic Mexican youth is the journey itself to understand the lay of the land and be seen as part of the social landscape of the city.”

Leal’s paper, “Mapping the city from below: Approaches in charting out Latinx historical and quotidian presence in metropolitan Los Angeles: 1990–2020,” was published this spring in the European Journal of American Culture.

Leal will build on the current research with related projects including a collaborative open-source public project in which Latinx community members can chart landmarks in Southern California, and a podcast series titled “The Discursive Power of Rock en Español and the Desire for Democracy," funded from a grant by the University of California Humanities Research Institute.