More than a century ago, a Romeo and Juliet-esque tragedy unfolded in the desert southwest. The antagonist, Willie Boy, shot and killed the shaman, William Mike, and eloped with William Mike’s daughter, Carlota, who met her demise at the hands of the pursuing posse.

The story has been framed and reframed for generations from the settler perspective, including the Harry Lawton book “Willie Boy” and a 1969 Hollywood movie starring Robert Redford and Robert Blake. The resulting narrative has endured in large part because cultural law has prevented the Chemehuevi community from speaking of the dead.

Click here for an updated story of The Last Great Manhunt

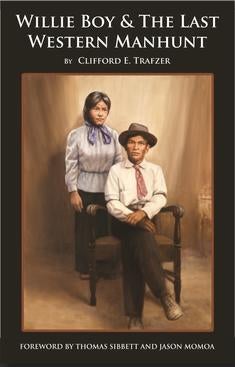

Clifford E. Trafzer, distinguished professor of history and Costo Chair in American Indian Affairs at UC Riverside, explores this fateful saga from the perspective of the Native community in his book, “Willie Boy & The Last Western Manhunt.”

Boy meets girl

Willie Boy was born into a Nuwuvi family in the Chemehuevi Valley in 1882. He entered the world at a contentious time as more white settlers pressed into the area in search of gold, land, and opportunities. Willie Boy learned the values of his culture as he walked the path of his ancestors. He also adapted to the white culture, learning English and working alongside white ranchers. As he grew, the cultural tug-of-war led to the misstep that set tragedy in motion.

In 1909, Willie Boy traveled to Oasis of Mara, known today as Twentynine Palms, where he hoped to find a wife. On that fateful trip, he first set eyes on his 16-year-old cousin Carlota, the daughter of shaman William Mike, chief of the Chemehuevi. Everyone in the community understood the couple could not wed — everyone but Willie Boy and Carlota.

By Chemehuevi tradition, parents arranged the marriage of their children to prevent violation to Nuwuvi incest laws. In addition, Willie Boy did not hold a status to marry a tribal chief’s daughter, and he was 12 years Carlota’s senior.

Carlota did not consult her elders, seek permission from her parents or announce to the larger community their intensions. Instead, she slipped away with Willie Boy in the cool desert darkness to elope. When both families learned of this reckless act, they brought the couple home and separated them. That should have been the end of the story, but in Trafzer’s book Chemehuevi elder Mary Lou Brown recalled her mother’s recounting of events, “Love is hard.”

'Love Is Hard'

A few months later, fate brought Willie Boy and Carlota together again, and this time Willie Boy sought William Mike’s permission to marry his daughter. He did not go alone. Willie Boy brought a gun, perhaps to shore up his own confidence as he confronted Mike, an intimidating man of formidable size, a shaman, a tribal chief, and a disapproving father.

No one can say for certain how the day unfolded, but in the end, William Mike lay dead. In the haze of trauma, Carlota ran off on foot with her beau.

Willie Boy had now committed two grievous acts in violation of Nuwuvi law – incest and murder. Then white lawmen became involved, and a posse was assembled. Trafzer’s revisiting of the episode portrays a media spewing a litany of racist, sexist, and slanderous stereotypes and lies.

Events quickly spiraled. Willie Boy and Carlota escaped southeast along the Morongo Hills, skirting the foothills of the San Bernardino Mountains. With each step, they set a course for the high desert. Believing they were out of harm’s way at The Pipes, they rested, but the posse drew near. Trafzer’s telling of the story holds that a posse member mistook Carlota for Willie Boy, shooting her in the back. Previous versions identified Willie Boy as her killer. After Carlota’s murder, the posse lost heart and returned to town with her body.

Stand-off at Ruby Mountain

Trafzer writes that the local newspapers continued to spin a sensational narrative. The public insisted the posse return to the cause. Willie Boy fled north to Ruby Mountain, leaving a trail for his pursuers to follow. At the same time, the sheriff began to round up Chemehuevi and Serrano people to prevent them from provisioning the fugitive’s escape.

From the slopes of Ruby Mountain, Willie Boy watched the lawmen approach. When the posse was within 30 yards, he opened fire. As an expert marksman, Willie Boy could have laid waste to the posse. Instead, he aimed for their horses, forcing them to approach on foot. The standoff lasted all day. As darkness fell, Trafzer asserts, Willie Boy slipped away for a second time.

Prodded by the media, the public thirsted for justice. Again the posse regrouped, but after the gunfight at Ruby Mountain, no one knew Willie Boy’s movements. Despite the lack of information, they assured the public that the outlaw had committed suicide, presenting photographs of a body that didn’t show the face. The sheriff’s posse burned the body in the desert, opting against convention. Over time, the story of Willie Boy’s suicide became solidified as fact.

Trauma echoes through time

The Chemehuevi were broken by these events, Trafzer writes. They feared the restless spirit of William Mike, who was not properly laid to rest, may come back to the village and do them harm. The tribe chose to leave Oasis of Mara and relocate to Cabazon, where they had worked in the past. Their stay was brief, and soon the families dispersed across the region. Generations later, in 1975, the Chemehuevi received formal tribal status, and the families reunited outside Indio, Calif.

As time passed, many Native elders gave voice to the fateful events that unfolded in 1909. Trafzer said their versions all agreed on one point – Willie Boy escaped the manhunt. According to Cahuilla elder Katherine Siva Saubel, Willie Boy made his way back to his people.

After the standoff at Ruby Mountain, the Chemehuevi runner moved swiftly north across the Mojave Desert to Pah-Rimpi (Water Rock), commonly called Pahrump. Willie Boy arrived at this sacred place for the Nuwuvi people at a time when his life was at a crossroad.

“Pahrump is the home of red ant hill, which has a spiritual relationship to the Spring Mountains,” said Trafzer. “He went to the area to wash himself clean of the shameful act. He asked for help and the shaman could not deny him.”

As he stood on the hallowed ground, Willie Boy began a long trek to redemption. The narrative closes as Willie Boy finds peace and is laid to rest in holy ground in the shadow of Snow Mountain.

Carlota’s motivation, thoughts and feelings have been lost to time. She died when she was quite young, and her relatives held to the mores of their tribe and stopped speaking of her. From what Trafzer has learned, Carlota understood the severity of her actions and joined Willie Boy willingly.

Setting the Record Straight

The actor Jason Momoa learned about this tragic story and reached out to Chemehuevi Indian leadership with his plan to produce a new, full-length motion picture, “The Last Manhunt.” In the course of his research, Momoa formed a relationship with Trafzer, who later consulted with the film's screenwriter.

Momoa consulted with Nuwuvi people to produce an accurate portrayal of their culture, language, song, and story. The cast includes Native actors from the Tlingit and Koyukon-Athabascan, Native Hawai’ian and Lakota tribes. The film also builds on the expertise of Nuwuvi singers who, for the first time, sing salt songs, or funeral songs, as a final farewell to William Mike and Carlota.

Momoa is working to distribute the film and bring it to a broad audience.

“As a historian, I want to construct the truth, which is like fishing in different ponds,” Trafzer said. “If I concentrate only on what the posse said I get one story, but if I go over to another pond, I am going to find something different. We need to be broad minded and think about the facts when looking at the past.”