Genetic analysis of COVID-19 samples at UC Riverside is helping state officials prepare for potential infection surges caused by new variants of the disease.

Variants, like Delta or Omicron, can render COVID-19 vaccines or antibody treatments less effective, and they can also be spread more easily than the original strain of the virus. UCR’s genetic data helps the California Department of Public Health detect variants and gives officials a real-time view of how they may be migrating through the state.

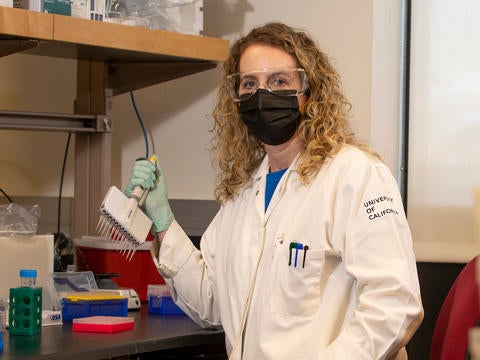

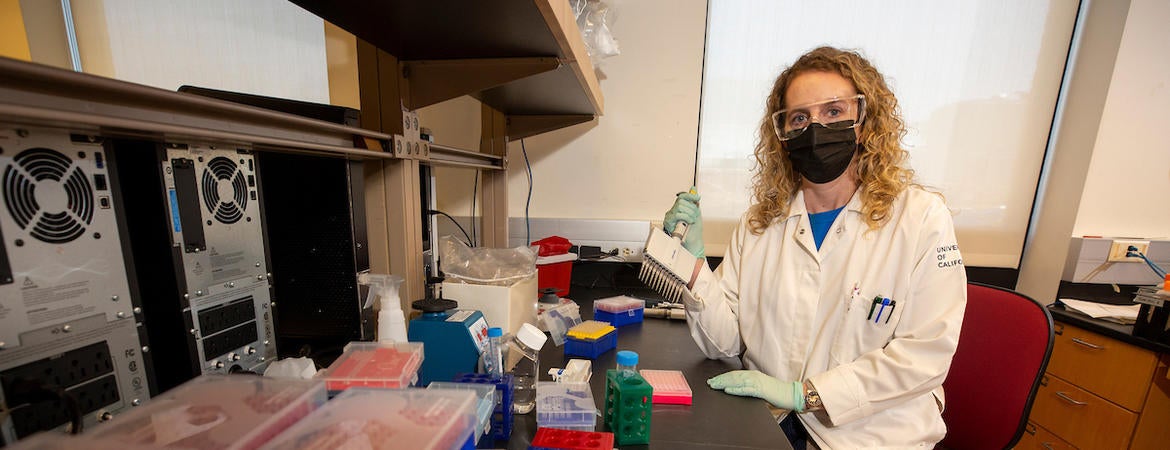

“Health professionals need to know if they’re on the verge of a surge, so they can warn hospitals and cities for what may be coming,” said Holly Clark, a researcher with UCR’s Institute for Integrative Genome Biology who has dedicated part of her laboratory to this work.

Clark has been doing this work for much of the pandemic, alongside a consortium of scientists at other University of California laboratories and independent sites.

Though she has analyzed nearly 4,000 COVID-19 samples since September 2021, the accuracy of Clark’s work has remained reliably high. As a result, the state is renewing its contract with UCR to continue hunting for variants.

“I am proud to say that UCR's sequences are in the highest quality tier of the public health department’s analysis sites,” said Katherine Borkovich, divisional dean of life sciences at UCR and principal investigator overseeing the project. “Our efforts contributed to the epidemiological tracking of the Omicron variant, and I expect they will help identify others, should they arrive.”

Borkovich notes that the analysis is performed on RNA molecules extracted from positive COVID samples, not on live virus. Inactivated samples from various counties are sent to a central state laboratory that further deactivates the virus by removing its infectious outer layer.

“This virus without the external protein coating cannot infect a human cell,” Borkovich said. “We still treat the samples as though they are live, but they aren’t. They are very, very safe.”

RNA is a type of nucleic acid that living cells and viruses use to make proteins. It is composed of long strings of smaller molecules called nucleotides. It is the order of these nucleotides in the samples’ RNA that Clark is analyzing. When the order of the nucleotides differs from other samples, it may be a variant.

The samples are also anonymous. Once Clark’s data is decoded by Brandon Le, an assistant bioinformatics project scientist, it is sent back to the public health department. There, scientists can trace the region from which the sample came.

Clark, a UCR alumnus, came to the institute’s genomics core in 2011. Her COVID work is similar to the analysis she performs on other types of biological samples.

“I’m happy to be involved in this project because it’s so important to know what the variants are,” Clark said. “If we don’t know what’s coming, we can’t support healthcare workers. This is our way of contributing to the pandemic response.”