Corals are keystone species for reef and marine ecosystems but coral bleaching due to climate change and ocean warming is killing them. A new open access study by researchers at the University of California, Riverside, aims to shed light on how to reverse the damage and save corals.

Corals, together with sea anemones and jellyfish, belong to a group of animals called cnidarians that receive some of their nutrients through a symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic algae living inside their cells. High ocean temperatures cause a breakdown in the symbiosis resulting in a ‘bleached’ coral that has expelled the algae. If symbiosis is not initiated within a few weeks, the coral will starve to death.

The new study finds that although photosynthesis by algae is a key part of the symbiotic relationship it is not required to initiate symbiosis. The discovery adds to the little-understood relationship between cnidarians and algae at the molecular level and offers insight into how to jump start the symbiotic relationship between the two organisms after a bleaching event. It could also lead to strategies that might prevent warmer oceans from breaking the symbiotic relationship between the two organisms and saving what remains of the world’s corals.

Cnidarians form a mutualistic symbiosis with photosynthetic algae from the dinoflagellate family Symbiodiniaceae that live inside of their host cells. The algae perform photosynthesis, fix carbon dioxide into sugars, and then give that to their hosts. Some species of coral are completely dependent on the food they receive from their algal symbionts and will die without it.

In return the algae receive nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus from the prey that the host catches. Photosynthesis is a key part of this symbiotic relationship, but it was not known if this symbiosis can form without photosynthesis.

Robert Jinkerson, an assistant professor of chemical and environmental engineering at UCR, and Tingting Xiang, an assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, led a team to make the first mutants in Symbiodiniaceae algae—isolate mutants that lacked the ability to photosynthesize—and use these mutants to investigate symbiosis with cnidarians

“We were very excited to be able to generate six photosynthetic mutants and then use those mutants to start to probe the symbiosis between these algae and their hosts,” Jinkerson said.

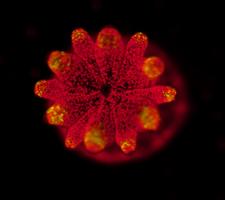

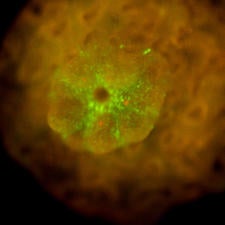

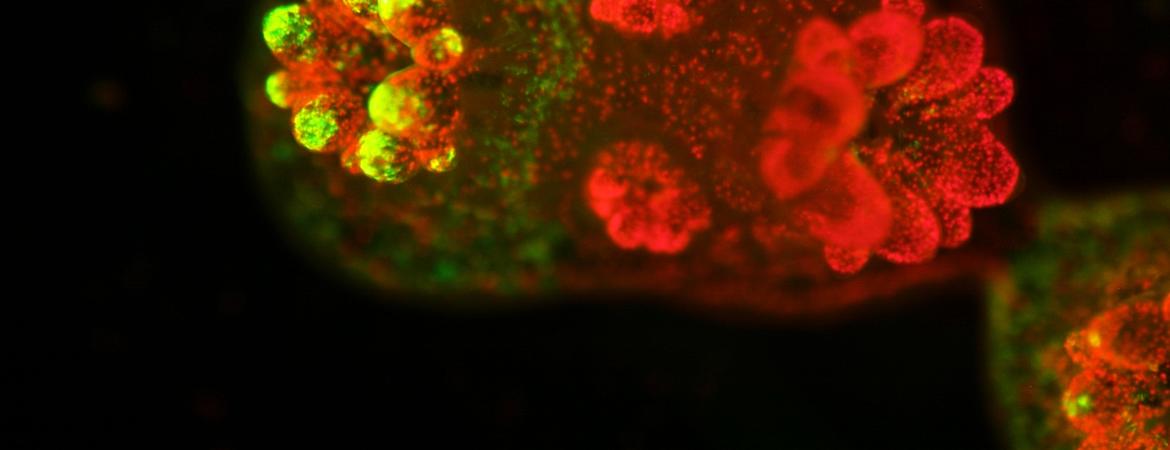

The team introduced the mutant algae into seawater tanks that contained sea anemones (Exaiptasia pallida) that had not yet established symbiosis with any algae. After just one day the algae could already be found within the sea anemone’s tentacles, even without photosynthesis.

To learn if the algae could survive in sea anemone host tissue without photosynthesis for longer periods of time, the researchers infected some sea anemones in darkness with mutant and non-mutant algae and kept them in darkness for six months. Even after six months, algal cells were still observable in the sea anemone’s tissues. Although able to infect the host cells and maintain itself for six months, the algae did not reproduce and proliferate in number.

The group also tested four other species of algae known to form symbiotic relationships with the sea anemones and found that they too could initiate symbiosis in the dark.

Jinkerson, Xiang, and their colleague Masayuki Hatta in Japan then introduced the algae in darkness into a tank containing juvenile polyps of a stony coral, Acropora tenuis. The algae infected the coral successfully in the dark. Unexpectedly, the algae were able to proliferate in the coral tissues without photosynthesis, something not observed in the sea anemones.

Finally, to learn if the pattern held true for the third member of the cnidarian group, the researchers added the algae to a darkened tank of upside-down jellyfish (Cassiopea xamachana) polyps. Once again, the algae infected the polyps, though not as successfully as in the sea anemone and coral.

Symbiosis establishment can proceed without photosynthesis in coral, jellyfish, and sea anemone hosts, but different aspects of the relationship, such as proliferation of the algae without photosynthesis, depends on the specific host–algae relationship.

“Our study highlights the power of forward genetic approaches to probe cnidarian Symbiodiniaceae symbiosis and provides a promising platform to answer key questions in symbiosis and ultimately develop strategies to save corals,” said Xiang.

The discovery that photosynthesis is not essential to begin symbiotic relationships is a step toward finding ways to help cnidarians survive climate change.

“Time is of the essence regarding the protection of the coral reefs, and our hope is that these mutants will allow ourselves and others to increase the overall pace towards this goal,” said co-author Joseph Russo, a doctoral student in Jinkerson’s lab.

Jinkerson, Xiang, Hatta, and Russo were joined in the research by Casandra R. Newkirk, Andrea L. Kirk, Richard J. Chi, Mark Q. Martindale, and Arthur R. Grossman. The open-access paper, “Cnidarian-Symbiodiniaceae symbiosis establishment is independent of photosynthesis,” is published in Current Biology and available here.

Header photo: Fluorescence image of coral Acropora juvenile polyps hosting the symbiotic Symbiodiniaceae (Breviolum minutum) algae, shown as red dots. Green color is the endogenous green fluorescence from corals. (Robert Jinkerson/Tingting Xiang)