As scientists look for ways to clean up “forever chemicals” in the environment, an increasing concern is a subgroup of these pollutants that contain one or more chlorine atoms in their chemical structure.

In a recent study published in the journal Nature Water, University of California, Riverside, environmental and chemical engineering Associate Professor Jinyong Liu and UCR graduate student Jinyu Gao describe newly discovered chemical reaction pathways that destroy chlorinated forever chemicals and render them into harmless compounds.

Known formally as PFAS or poly- and per-fluoroalkyl substances, forever chemicals have been used in thousands of products ranging from potato chip bags, stain and water repellents used on fabrics, cleaning products, non-stick cookware, and fire-suppressing foams. They are so named because they persist in the environment for decades or longer due to their strong fluorine-to-carbon chemical bonds.

Chlorinated PFAS are a large group in the forever chemical family of thousands of compounds. They include a variety of non-flammable hydraulic fluids used in industry and compounds used to make chemically stable films that serve as moisture barriers in various industrial, packaging, and electronic applications.

Recent discoveries of previously unknown chlorinated PFAS pollutants in the environment are raising new concerns. For example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported discoveries of these pollutants in wells and tributaries to the Delaware River near a chemical plant in southwestern New Jersey.

Forever chemicals have seeped into groundwater supplies throughout the nation, and they have been linked to a host of ill health effects, including cancer, kidney disease, and hormone disruptions. The EPA is now promulgating new regulations to spur cleanups throughout the nation.

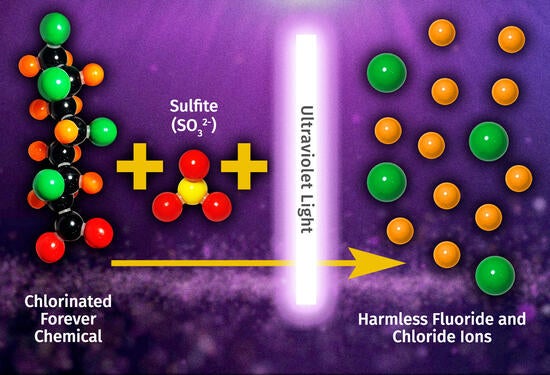

Liu’s study used ultraviolet light and sulfite to cleave the chlorine-to-carbon bonds. This set off a chain of chemical reactions that also cleaved carbon-to-carbon and carbon-to-fluorine bonds, which is critical for rapid and near-complete defluorination of PFAS compounds needed for pollution cleanup efforts.

“Our team is examining more pathways and strategies for PFAS degradation, and our ultimate goal is to cut all of the carbon-fluorine bonds to completely detoxify the PFAS pollutants,” Liu said.

Liu’s new insights on chlorinated PFAS compounds builds on his team’s discoveries since 2016 to destroy various PFAS pollutants in heavily contaminated water by using a combination of ultraviolet light and sulfite. These methods have since been detailed in seven scientific journal papers. They hold promise because sulfite is a low-cost compound used as a food preservative and ultraviolet light is already used in tap water treatment facilities to kill potentially harmful microbes.

Remarkably, PFAS destruction by this process produces fluorine ions, which are commonly added to municipal water supplies to improve dental health.

Liu’s work on the destruction of PFAS compounds is generating interest from industry. His group has been working with three companies interested in scaling up his laboratory work to conduct cleanups at US Air Bases and airports through government contracts.

A major source of PFAS pollution in groundwater and below military air bases and commercial airports are spills of fire-suppressing foams used for decades to extinguish aviation fuel fires. Invented by the US Navy in the 1960s, these foams form an aqueous film around the burning liquid, which quickly deprives the fire of oxygen and extinguishes it.

The title of Liu’s most recent study is “Photochemical Degradation Pathways and Near Complete Defluorination of Chlorinated Polyfluoroalkyl Substances.” Liu is the corresponding author and Gao is the lead author. UCR-affiliated co-authors include UCR Assistant Professor Yujie Men, UCR grad students Zekun Liu and Shun Che, and UCR postdoc researcher Dandan Rao.

Jinyong Liu, Goa, Men and Che are also co-authors of another recent paper in Nature Water that reported the discovery of two bacteria species that destroy chlorinated PFAS compounds, giving hope for biological cleanup strategies.