It came as a surprise to Professor David Lo and his graduate student Diana Del Castillo when they were recently consulted by researchers in Israel for their expertise on specialized cells called Microfold cells, or M cells, which are mostly known for their presence in the intestinal epithelium. The Israeli group had identified similar cells in the thymus, an organ located just above the heart that makes lymphocytes — white blood cells that play an important role in the immune system and protect the body against infection.

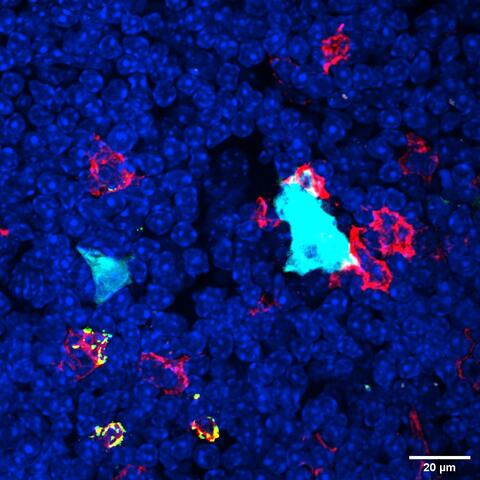

Lo, a distinguished professor of biomedical sciences in the UC Riverside School of Medicine, and Del Castillo, who are co-authors on the research paper published in Nature, confirmed the newly discovered cells in the thymus are just like M cells. Acting like gatekeepers, M cells are specialized antigen-delivery cells for the immune system in organs like the intestine and lung. They play a key role during the development of the body’s immune system.

The researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, led by Jakub Abramson, initiated the mouse study on the thymic epithelium before contacting Lo, whose research interests include understanding how M cells in the gut and airways work to build our immune system.

“I have been working on these cells for several years, so when the Israeli team contacted me, I was intrigued,” Lo said. “I learned this group had been doing studies on the cellular architecture of stromal cells — cells that make up certain types of connective tissue — in the thymus and, using a new advanced method, had discovered a population of cells much like the M cells we see in the gut and airways. In my own research, I had simply never thought to look for M cells in the thymus.”

Fortuitously for the Israeli scientists, Del Castillo, under Lo’s guidance, had been studying mucosal tissues — tissues that line some of the body’s canals and organs — in mice in the lab and was able to answer several questions, such as where in the thymus the newly discovered cells are located and what they are doing there.

“These particular M cells are limited to a specific region in the thymus and have unique associations with different cell types and functions,” Del Castillo said. “Questions these cells have already prompted include how similar are they to M cells elsewhere in the body and what is different about where they have been found.”

Lo explained that for many years the thymus has been a tissue of interest to immunologists because most of the immune system’s development is centered and dependent on the thymus.

“It’s still an ongoing deep puzzle that continues to attract interest,” he said. “The thymus offers clues to how the immune system got its start. This complicated organ, with so many different stromal cell types and interactions, is responsible for producing lymphocytes that protect us from infection.”

According to Lo, the newly discovered M cells are extremely similar to the M cells seen in the gut and airways.

“But the thymic M cells have different developmental origins, which is an interesting puzzle in itself,” he said. “After they develop, they look very much like the ones we have been studying in the gut. As we know, M cells capture viruses and bugs that enter the airways and hand them off to the immune system, which then responds to the infectious agents. Are the M cells doing the same thing in the thymus in terms of organization and function? That’s what we would like to know.”

Del Castillo, who is working toward her doctoral degree in biomedical sciences, used genetically engineered mice to tackle the questions from the Israeli researchers.

“We found the new cells were scattered in the medullary region of the thymus,” she said. “This has interesting implications in terms of the role and compartmentalization of the thymus, such as how these cells may function to regulate lymphocyte training within this organ.”

Lo and Del Castillo were surprised to find that many steps involved in shaping an immune response in various parts of the body seem to be echoed in the thymus.

“It is fascinating to see that many of these early cell interactions and development we have studied closely in the peripheral immune system take place in the thymus,” Lo said. “We had not anticipated to see these interactions here. It’s like watching a short video in the thymus about what is happening big-scale out in the periphery.”

The thymus also ensures that lymphocytes do not accidentally attack our own tissues; the thymic medulla is where these decisions are made, the UCR scientists said.

“The newly discovered M cells are part of this decision-making process,” Del Castillo said. “The production of antibodies in the peripheral immune system to fight off infectious organisms involves several steps and many cells interacting with each other. What is fascinating is that some of these interactions are recapitulated in the early stages of the development of the thymic M cells.”

According to Lo, the thymic M cells could be seen as being trained to function later, when needed, in the periphery in such a way that they are ready to communicate and interact with other cells.

“The thymus is complicated because it creates a whole functional immune system and repertoire, and we know many component parts play a role in its performance,” he said. “We didn’t expect M cells to even show up in the thymus. This is, therefore, a satisfying discovery because it is so clearly connected to similar processes happening in the gut and airways, which is where 60-70% of our infectious agents enter our bodies.”

The research paper, Lo’s tenth publication in Nature, is titled “Thymic mimetic cells function beyond self-tolerance.”

Header photo credit: janulla/iStock/Getty Images Plus