California’s native wildflowers are being smothered by layers of dead, invasive grasses. A new UC Riverside study shows that simply raking these layers can boost biodiversity and reduce fire danger.

The study, published this week in Restoration Ecology, tested whether removing thatch — dead leaves and debris — could allow native plants to germinate and grow. Compared to other techniques for managing invasive grasses, such as controlled burns, hand weeding, and spraying herbicides, raking is decidedly less labor intensive and more ecologically friendly.

“In these ecosystems, native seeds often fall on thick layers of thatch and can’t germinate. Raking the thatch lets light in and gives native plants a chance to grow,” said Marko Spasojevic, study author and UCR associate professor of plant ecology.

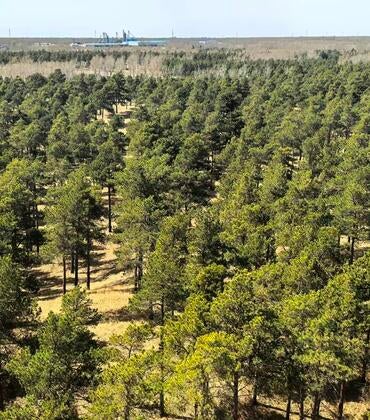

In grasslands near the UCR campus, researchers used a grid of paired plots — one raked and one untouched — to measure plant community changes over the course of three years. Results showed raking increased plant diversity overall, reducing invasive grasses like ripgut brome while increasing both native and exotic wildflowers, known as forbs.

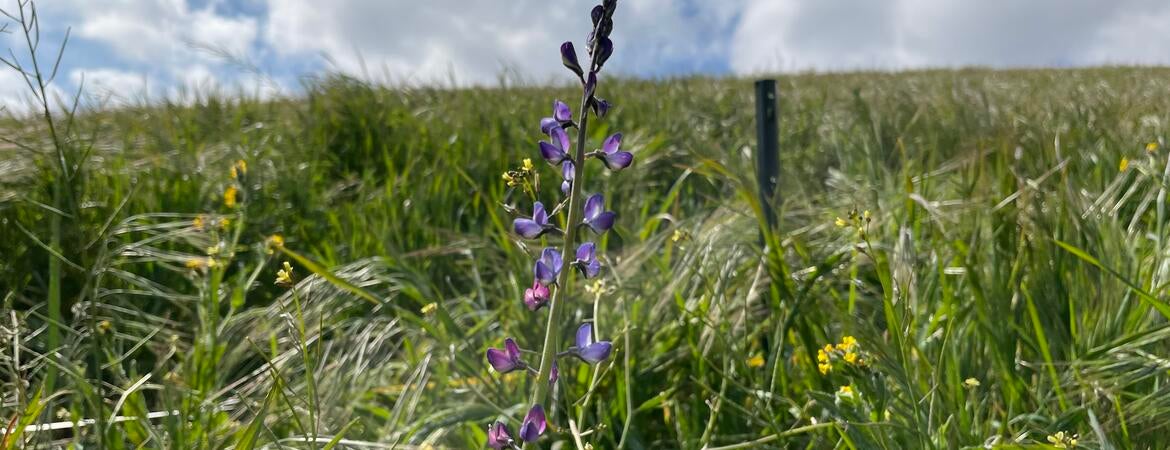

Ripgut brome, a dominant invasive grass, earned its name from its sharp, bristly hairs, which can injure grazing animals. “It’s super nasty for sheep and cattle to eat,” Spasojevic said. Meanwhile, native flowers like the common fiddleneck, prevalent in Riverside, benefited modestly from raking.

While raking reduced invasive grasses, there was a trade-off. It also increased certain exotic wildflowers, such as Sahara mustard, which can be highly invasive.

“Raking boosted native wildflowers by about 5% and exotic forbs by about 7%,” said Advyth Ramachandran, who co-led the project as a UCR undergraduate and now studies plant ecology at the University of Colorado Boulder. “This doesn’t mean raking isn’t worthwhile. It’s a simple, low-cost method that could be a first step for restoring these systems.”

The roots of this project stretch back decades. The study site has been used for research since the 1990s. The specific plots used in this study were originally created for an introductory biology class in 2003 and then were later abandoned. During the pandemic, Ramachandran and other UCR students revived the site, launching a grassroots research initiative through the university’s SEEDS club.

“We as undergraduates built this project ourselves from scratch, writing protocols, identifying species, and involving over 20 undergraduates,” Ramachandran said. “It’s rare for undergraduates to initiate and lead publishable research like this.”

Spasojevic credits the project’s success to its accessibility. “The research site is on campus, so students could sample between classes. It lowered barriers for involvement and became a rich mentorship opportunity,” he said. The SEEDS initiative remains active, with students continuing to collect data for a fifth consecutive year.

The team’s findings have practical implications for land managers seeking low-cost methods to restore native plant diversity in grasslands and coastal sage scrub ecosystems.

Native plants provide food and habitat for local wildlife, support pollinators like bees, and reduce soil erosion. Invasive grasses, on the other hand, not only outcompete native species but also increase wildfire risk with their dense, highly flammable layers. Boosting native wildflowers is key to restoring and maintaining healthy ecosystems.

“This project shows how small actions—like raking—can make meaningful differences in our ecosystems,” Ramachandran said. “It’s a promising step toward restoring California’s native landscapes.”