Douglas McCulloh, an engaging and unconventional California photographer and for the past several years the head of the two UCR ARTS museums, died on Sunday, Jan. 5 following a short illness.

McCulloh, who was 64, curated the current UCR ARTS exhibition on Ansel Adams, which includes Adams’ 1960s work on University of California campuses. He had several other exhibitions and personal projects in the works, as well.

The avuncular McCulloh possessed an offbeat wit and constant curiosity, and dressed perpetually like a photographer on assignment at an art opening: In dark blazer, black tee, jeans, and ball cap.

“By being a genial giant — in stature, grace, wit, and capacity, which was huge — Doug left an incredible mark on people and on this place of San Bernardino and Riverside, not to mention UCR,” said Catherine Gudis, a UCR history professor and past collaborator of McCulloh’s. “His photography, curation, and unwavering support for others, especially local artists, put the IE on the map and mental landscape of those of us who came here from elsewhere and wanted to viscerally know more as well as those born and bred here.”

A longtime collaborator at UCR’s California Museum of Photography, or CMP, McCulloh formally joined the museum in July 2018 as senior curator. In 2023, McCulloh was named interim executive director of UCR ARTS, which includes the CMP and the Culver Center of the Arts.

“He approached situations with calm, with empathy, and with his sharp sense of humor,” said Nikolay Maslov, curator of film and projects for UCR ARTS. “His unwavering trust in and support of the entire UCR ARTS team cultivated a vibrant period of exhibitions, programs, and initiatives.”

McCulloh graduated with two bachelor’s degrees from UC Santa Barbara, and a Master of Fine Arts from Claremont Graduate University. He is a five-time recipient of funding support from the California Council for the Humanities.

Two themes ran through his work: chance and geography.

“I was raised with the idea that everything’s contingent, everything’s chance-y, and if the world operates through chance, then why not use chance as a way to engage with the world — and that’s what art can do,” McCulloh said in a 2019 UCR News profile.

He was one of six artists who transformed an abandoned Southern California F-18 jet hangar into the world's largest camera to create the world's largest photograph. “The Great Picture” was featured at Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing; Art Center College of Design, Los Angeles; Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.; and Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans.

An early collaboration with the CMP was the 1999 exhibition “Chance Encounters .” For the exhibition, he gridded a map of urban Los Angeles County into 5,151 quarter-mile squares and randomly selected a quarter-mile section each day, then spent the day collecting photographs and stories from there. The project took seven years.

For “Dream Street” — a street he named when his wife, Dawn, won naming rights in a silent auction — he chronicled the transition of a San Bernardino County housing development, from the time of its incarnation as a strawberry field through construction. For “On the Beach,” he and a collaborator set up a kiosk and waited to see who would show up.

His first exhibition as senior curator at UCR ARTS turned a lens on the Inland Empire. “In the Sunshine of Neglect” was a collection of 54 photographers and 194 photographs.

McCulloh collaborated for 15 years with Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing Susan Straight, including on the 2013 Riverside Art Museum’s “More Dreamers of the Golden Dream” (described as “a love letter to generations of Riverside’s Eastside community”) and “Wild Blue Yonder,” a 2014 exhibition recording the many hidden stories of Southern California veterans in Riverside and the Inland Empire.

“Douglas McCulloh brought his immense curiosity, visual acumen, and love of narrative to the world,” said Straight, a National Book Award finalist who — like McCulloh — has trained her creative lens on Southern California.

A current project was “American Cross,” in which McCulloh drew bisecting lines across the U.S. and made photographs along the trajectory of those lines at every point he could reach. He had completed 4,600 of his intended 5,000-mile journey at the time of his death. Also in its last stages is a book from a Los Angeles Public Library commission to document the Hollywood neighborhood.

His wife of 42 years, Dawn Hassett, was also his close collaborator, including as his editor. She worked with him on the publication of six photography books and catalogs.

McCulloh long espoused the virtues of “making trouble” as an artist. It’s a phrase he often invoked when closing conversations and emails.

“He always said he was a troublemaker,” Hassett said. “He believed artistic practice needed to challenge the status quo. It needed to have a critical stance in the world.”

McCulloh was an avid reader who, since college, had tracked the books he read, sharing an end-of-year list with friends. He was reading Toni Morrison’s “A Mercy” at the time of his death; there is a bookmark on page 113, where he left off.

“He was his work,” Hassett said. “He’s gone and the only way he lives on is through his work. The more people can experience his work, the more life he has.”

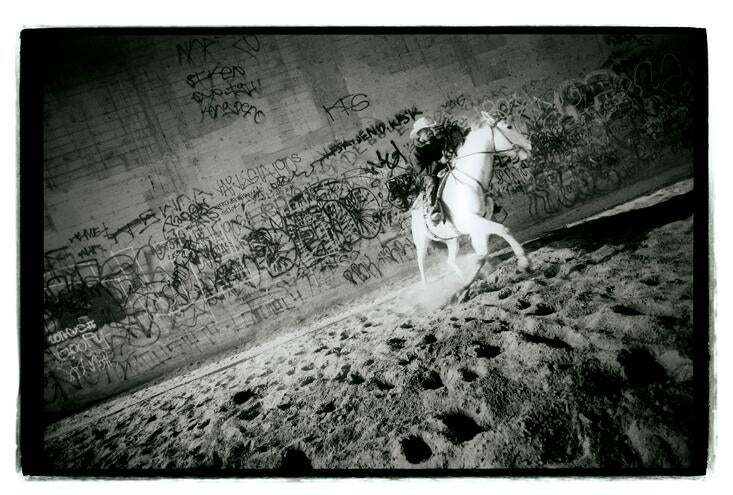

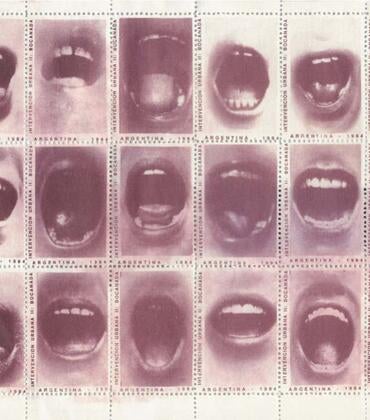

Following is a selection of McCulloh’s images, provided with captions by Hassett.

Feature image of McCulloh is by UCR photography manager Stan Lim, from 2019.