New research by the Atacama Cosmology Telescope, or ACT, collaboration has produced the clearest images yet of the universe’s infancy – the earliest cosmic time accessible to humans. Measuring light that traveled for more than 13 billion years to reach a telescope high in the Chilean Andes, the new images reveal the universe when it was about 380,000 years old — the equivalent of hours-old baby pictures of a now middle-aged cosmos.

The research has put the standard model of cosmology through a rigorous new set of tests and show it to be robust. The new images, which show both the intensity and polarization of the earliest light with unprecedented clarity, reveal the formation of ancient, consolidating clouds of hydrogen and helium that later developed into the first galaxies and stars.

The new pictures of this background radiation, known as the cosmic microwave background, or CMB, add higher definition to those observed more than a decade ago by the Planck space-based telescope.

Steve Choi, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at UC Riverside, played a key role in acquiring the new dataset by developing and deploying the telescope’s detectors. Working with a small team, he assembled, tested, and installed the detector arrays, ensuring they performed well in both the lab and field. On the analysis side, he led the earlier angular power spectrum measurements and first implemented “curved-sky” power spectrum methods for ACT.

“By observing the cosmic microwave background with unprecedented detail, we have provided the most precise measurements to date of the universe’s age and its fundamental properties,” Choi said. “This new image is an extraordinary achievement, not only for its stunning clarity but also for its confirmation of the standard model of cosmology, reaffirming our understanding of how the universe came to be.”

In the first several hundred thousand years after the Big Bang, the primordial plasma that filled the universe was so hot that light could not propagate freely, making the universe effectively opaque. The CMB represents the first stage in the universe’s history that we can see —essentially the universe’s baby picture. The new images give a clear view of very subtle variations in the density and velocity of the gases that filled the young universe, helping scientists answer longstanding questions about the universe’s origins.

ACT specializes in observing the universe through millimeter-wavelength light, allowing scientists to probe distant galaxies, black holes, and massive galaxy clusters, all the way back to the CMB. The telescope can see photons that are more than 13 billion years old, extending farther into the past than even the James Webb Space Telescope.

The work has not yet gone through peer review, but the researchers will present their results at the American Physical Society annual conference on March 19.

“What makes this super exciting is the new level of precision with which we have imaged the universe in its infancy,” Choi said. “These images allow us to more stringently test the fundamental model of the universe. We independently confirm that the standard model remains a remarkably successful description of our universe. At the same time, we rule out many competing models. Our results contribute to the ongoing ‘Hubble Tension’ that describes the unresolved disagreement among cosmologists over the expansion speed of the universe.”

In recent years, cosmologists have disagreed about the Hubble constant, the rate at which space is expanding today. Using their newly released data, the ACT team has measured the Hubble constant with increased precision. This data will play a critical role in understanding the universe’s expansion and how it led to the formation of the structures we observe today.

This research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (AST-0408698, AST-0965625 and AST-1440226 for the ACT project, as well as awards PHY-0355328, PHY-0855887 and PHY-1214379), Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania, and a Canada Foundation for Innovation award. The project is led by Princeton University and the University of Pennsylvania, with 160 collaborators at 65 institutions. ACT operated in the Atacama Astronomical Park in Chile from 2007-2022 under an agreement with the University of Chile.

This news release is a modified version of Princeton University's news release.

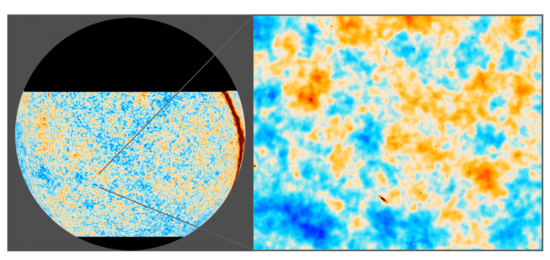

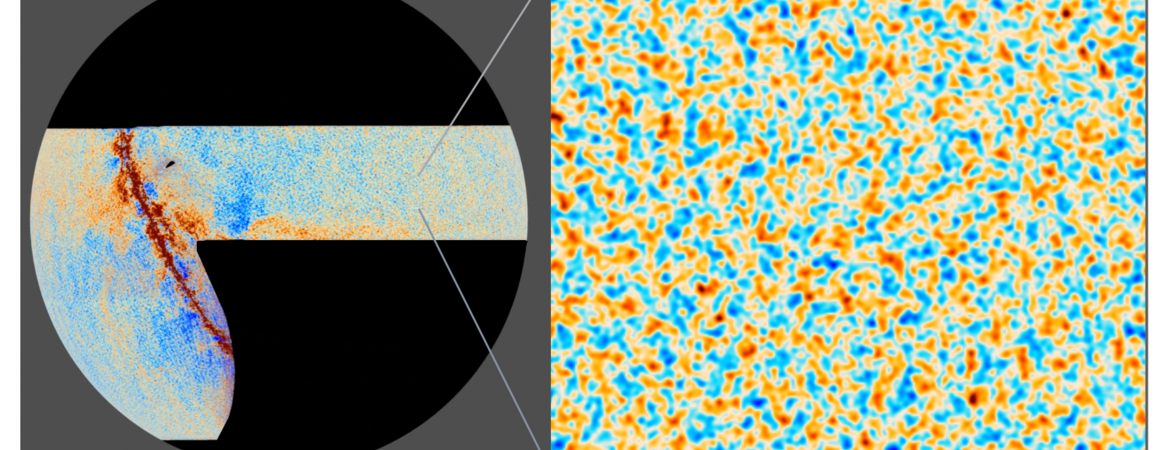

Header image: A piece of the new image that shows the vibration directions (or polarization) of the radiation. The zoom-in on the right is 10 degrees high. Polarized light vibrates in a particular direction; blue shows where the surrounding light’s vibration directions are angled towards it, like spokes on a bicycle; orange shows places where the vibration directions circle around it. This new information reveals the motion of the ancient gases in the universe when it was less than half a million years old, pulled by the force of gravity in the first step towards forming galaxies. The red band comes from our closer-by Milky Way. Credit: ACT Collaboration; ESA/Planck Collaboration.