For decades, Californians, and by extension, Americans, have lived alongside unhealthy flame-retardant chemicals embedded in their furniture, thanks to a few lines in a 1970s state law.

David Volz, University of California, Riverside professor of environmental toxicology, has long studied how those chemicals escape into indoor air and settle in household dust. In the journal Environmental Science and Technology, Volz details the history of flame retardants in our upholstered furniture and argues that lawmakers should close a regulatory gap allowing their use before it’s too late. In this Q&A, he explains why it’s important that they do so.

Why are flame-retardant chemicals a concern?

They don’t stay put. These are additive chemicals, not bonded to the materials. Over time, they migrate into the air, settle into dust, and get inhaled or ingested. Some of the compounds used in the past — like penta-BDEs — are highly persistent. They’re linked to cancer, reproductive harm, and endocrine disruption. Even though we phased out that class of chemicals, we replaced them with organophosphate-based flame retardants, which can also be toxic. It’s the same story, just a different chemical family.

Do the newer flame retardants pose the same level of risk?

They’re generally less persistent, which is good, but they’re still harmful. They still migrate into the environment, and we still detect them in indoor spaces — homes, workplaces, cars. They’re just less bad. But “less bad” doesn’t mean safe. And none of them have shown clear benefits in terms of fire safety.

So the chemicals don’t actually work?

Not the way people assume. A Consumer Product Safety Commission study from about 15 years ago found that chemically treated furniture didn’t reduce fire spread compared to untreated pieces. What does work is a physical barrier — a layer of material between the foam and the fabric. That stops smoldering ignition, which is how most residential fires start. If you have a barrier, adding a chemical does little.

What prompted you to write a policy proposal?

During my sabbatical last year, I started digging into the origins of California’s flammability rule. I found that in 1972, two new lawmakers introduced a 141-word amendment to the Business and Professions Code that required furniture sold in California to meet a flammability standard. That short bill led to decades of chemical exposure. Manufacturers added flame retardants to comply with California, then sold the same products across the country. The entire U.S. got exposed, and we’re still dealing with the consequences.

Has California tried to fix the issue since then?

There’s been some meaningful progress. In 2013, we updated the flammability standard — known as TB117 — to focus on smoldering sources, like a lit cigarette. That change allowed manufacturers to use barriers instead of chemicals. Then in 2018, the state passed a bill that capped the concentration of flame retardants in furniture and mattresses to 1,000 parts per million, effective in 2020. But even that level is still high. And there’s one big gap left.

What’s the remaining loophole?

In 2023, California passed a law banning fiberglass fire barriers, which had been used as a chemical-free alternative. That ban takes effect in 2027. Without another policy change, manufacturers could legally pivot back to flame retardant chemicals to meet the flammability standard. That’s what I’m trying to prevent.

What’s your proposed solution?

Amend the legislation to prohibit flame retardant chemicals at any concentration in upholstered furniture. That would close the loophole and push manufacturers toward safer fire barrier alternatives — many of which already exist. There are fiberglass-free options used in mattresses today, made from materials like aramid or silica-infused rayon.

Why haven’t those been adopted more widely in furniture?

There are likely cost and design considerations, especially for furniture manufacturers. But the technology is there. The switch is feasible. What’s missing is regulatory pressure to make it happen.

What happens if no one acts before 2027?

We could see a resurgence of flame-retardant chemical use in furniture, undoing more than 15 years of progress. That means more chemicals indoors — in our homes, offices, cars, and schools. California drives the national standard, so the impact would ripple across the U.S. It’s a missed opportunity to reduce exposure for millions of people.

Why do you think this hasn’t gotten more attention?

Because it’s buried in the fine print of furniture regulations. But it affects everyone. Upholstered furniture makes up a huge share of the indoor environment. If we close this loophole, we’ll likely see indoor concentrations of these chemicals drop dramatically not just in California, but nationwide.

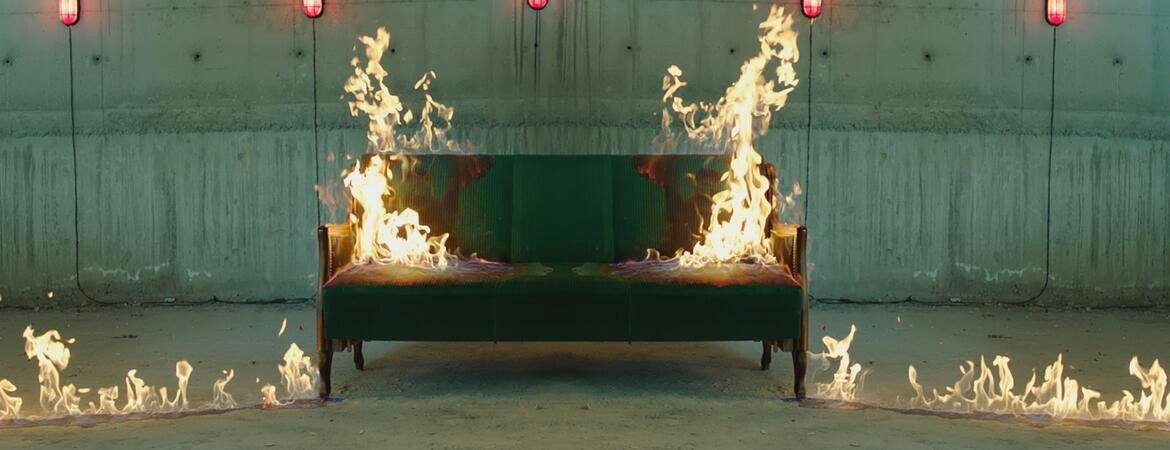

(Cover image: MeloyanMedia/Getty)