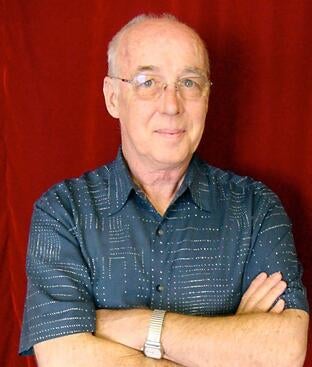

Over the Memorial Day weekend, Fred Strickler, distinguished professor emeritus of dance at UC Riverside, presented the archive of his life and career to approximately 40 invited guests at a private residence a few miles away from campus. Strickler passed away in Riverside just days later, on May 31, 2025. He taught dance — modern dance, tap dance, composition, and production — for 40 years at the university.

“It was important for Fred to present the archive collection to family and friends,” said Lizbeth Langston, a librarian emerita at UCR and dance historian who organized and curated the archive and leads the team that will deliver the collection to the Performing Arts Library at The Ohio State University, Strickler’s alma mater. “Developing and preparing the materials became a central focus of his last retirement years.”

The archive contains programs, posters, reviews, and articles that make up the print collection. Also included are correspondences and contracts Strickler had with dance companies. Numerous interviews, both video and audio, are part of the archive, as well as footage of Strickler dancing.

In a Facebook post in August 2024, soon after his 81st birthday, Strickler wrote that the collection is thoroughly organized and cross-refenced for future research.

“It provides a window into the worlds of professional modern dance, tap dance, education, collaboration, advocacy and the many great artists who inspired, influenced and contributed to my work,” he wrote. “This has been a twenty-year project that I’m honored to give to a whole field that has given me a life in dance. I couldn’t be more pleased.”

Strickler joined UCR in 1967, the year he met the dance historian Christena Lindborg Schlundt, one of the first members of the UCR faculty. Schlundt offered Strickler a position teaching modern dance technique and choreography in what was then the Department of Physical Education.

In 1972, Strickler and Schlundt founded the Program in Dance at UCR, which evolved into the Department of Dance. Strickler played a key role in the development of its undergraduate curriculum and later served as a resource to students in the Master of Fine Arts in Experimental Choreography program. He retired in 2007.

“Strickler’s legacy lives on in the department he helped co-found and in the generations of students he trained, many of whom are themselves now dancers, teachers, and choreographers,” said Daryle Williams, dean of the UCR College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences.

One of the invited guests who got to see the archive over the Memorial Day weekend was Anthea Kraut, a professor of dance at UCR who joined the faculty in 2003. Kraut’s connection to dance began in childhood, when she took up tap dancing as a young girl and continued into her early adult years.

“One of the great things about being in this department is getting to take classes from colleagues,” she said. “I was excited to take tap from Fred. He was an incredible dancer and teacher — clear, methodical, and deeply knowledgeable about the history of the form, which he wove into every lesson.”

Before joining UCR, Kraut was researching 1930s dance and found a transcript in the New York Public Library of an oral history Strickler had done with a tap dancer from that era. That was her introduction to Strickler and his work.

“It was striking to see his influence reach beyond teaching into historical documentation,” Kraut said. “Fred was originally hired at UCR to teach modern dance. Tap wasn’t offered in universities when he was a student, so he had shifted to modern to pursue his career. But he eventually brought tap back into his practice — and into UCR’s curriculum. That ability to bridge modern and tap was significant. He helped give tap a serious place in the academy, elevating its status through both his teaching and choreography.”

According to Kraut, Strickler’s legacy is a major part of why UCR has such a strong place in the history of dance in higher education.

“Fred was no-nonsense, and his approach gave tap dancing the weight and seriousness it deserves,” she said. “His impact on students, colleagues, and the broader tap community — especially on the West Coast — was profound. He helped train generations of dancers and contributed meaningfully to the preservation of tap’s history.”

Over the Memorial Day weekend, Kraut and other visitors of the archive got to talk briefly with Strickler over a Zoom call arranged by Langston.

“As Memorial Day weekend drew closer, Fred became weaker; he was in and out of the hospital,” Langston said. “He realized that he wouldn’t be able to be physically present on site, so we planned the Zoom meetings to insure his presence. I was very glad we could prepare the exhibits for guests so that they could hear and talk with Fred, and all socialize together.”

Strickler was born in 1943 in Michigan. In the 1970s, he began exploring tap dance, a form he had first studied as a child in Ohio. He studied modern dance as an undergraduate at the Ohio State University in Columbus. He choreographed more than 130 dance works in various styles, showcased at venues from high school auditoriums to prestigious locations like the Kennedy Center and Jacob’s Pillow. While starting at UCR, he trained with Bella Lewitzky and performed with her company until 1975. In 1974, he co-founded the modern dance group Eyes Wide Open Dance Theatre, active in Los Angeles until 1980.

Historian and performer Linda Tomko, a professor emerita of dance who joined UCR in 1989, recalls meeting Strickler at UCLA between 1977 and 1980 when he was teaching modern dance with the Eyes Wide Open Dance Theater. He also occasionally substituted at UCLA, where Tomko was completing her master’s degree.

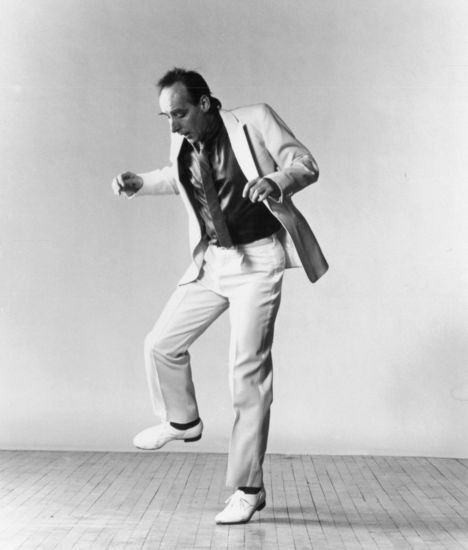

“I originally knew Fred as a prominent performer in the L.A. dance scene,” Tomko said. “By that time, he already had a national reputation and was gaining international recognition through his tours with the ‘Jazz Tap Ensemble.’ He was a wonderful tap dancer — completely in sync with the music. He was incredibly multi-talented and celebrated for his exceptional musicality and rhythmic innovation.”

According to Tomko, it was uncommon at the time for a dancer to work across multiple genres. Strickler was an exception. She said he began as a highly respected modern dance performer and choreographed in modern dance. He then increasingly shifted his performance focus to tap, particularly through his work with the Jazz Tap Ensemble, which he co-founded in 1979.

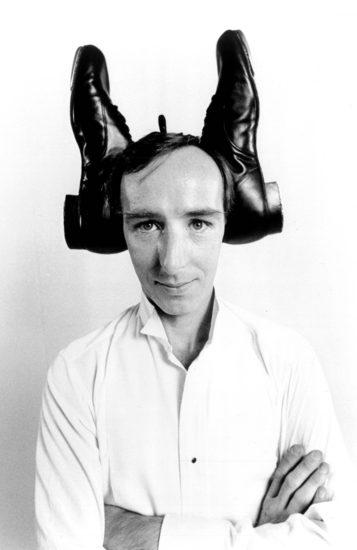

“He eventually choreographed in that style as well and earned national recognition for it,” Tomko said. “He had a vibrant personality and a kind of magisterial presence. He was a director in everything he did. He spoke with authority. After retirement, he often signed off emails with a personal motto that captured his spirit: ‘Life is big. Be big.’”

Strickler toured internationally with the Jazz Tap Ensemble. A key figure in the late 20th-century tap-dance renaissance, he performed widely as a soloist, notably premiering Morton Gould’s Tap Dance Concerto in 1983 with Gould conducting, and later performing it with major orchestras including the New York Philharmonic and the National Symphony Orchestra. His work also appeared in several acclaimed films and TV programs, such as the 1980 documentary Tapdancin’, the 1989 PBS special Tap Dance in America, and the 1999 film Four Dancers.

Jacqueline Shea Murphy remembers meeting Strickler in 1998, the year she joined the UCR faculty. A few years into her time on campus she went to see him perform at an outdoor venue. Strickler’s group came on stage and began their piece, but about 30 seconds in, he stopped the performance.

“He turned to the audience and said something to the effect of, ‘That just wasn’t good enough,’ and they started over,” Shea Murphy said. “That moment has stayed with me. It spoke volumes about his deep respect for the form and his high standards. He had this mix of confidence and integrity — he knew what he wanted from the work, and he wasn’t afraid to demand it.”

Shea Murphy agreed with what many people have said: Strickler was a beloved teacher. Students truly adored him, she said, and he consistently received outstanding teaching evaluations.

“His passion for tap was electric — you could feel it,” she said. “Thanks to Fred, tap was central to our program, from the beginning of our graduate curriculum. That inclusion had a lasting influence on the department, broadening our understanding of dance beyond just ballet or modern forms. Even for students who didn’t specialize in tap, Fred encouraged them to think choreographically through rhythm. That way of thinking — embodying rhythm as a foundational principle — has had a lasting impact on our students and our pedagogy. It’s incredibly significant — and rare — for a dance department to be founded with a tap dancer as a core faculty member. That choice shaped who we are.”

To support the UCR Department of Dance with a gift, please click here.