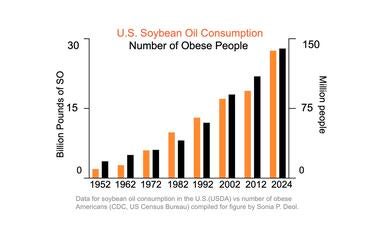

Soybean oil, the most widely consumed cooking oil in the United States and a staple of processed foods, contributes to obesity, at least in mice, through a mechanism scientists are now beginning to understand.

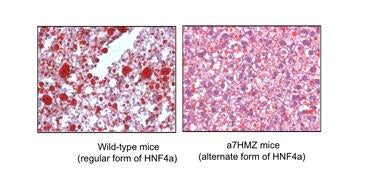

In an experiment conducted at UC Riverside, most mice on a high-fat diet rich in soybean oil gained significant weight. However, a group of genetically engineered mice did not. These mice produced a slightly different form of a liver protein that influences hundreds of genes linked to fat metabolism. This protein also appears to change how the body processes linoleic acid, a major component of soybean oil.

“This may be the first step toward understanding why some people gain weight more easily than others on a diet high in soybean oil,” said Sonia Deol, a UCR biomedical scientist and corresponding author of the study published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

In humans, both versions of the liver protein HNF4α exist, but the alternative form is typically produced only under certain conditions, such as chronic illness or metabolic stress from fasting or alcoholic fatty liver. This variation, along with differences in age, sex, medications, and genetics, may help explain why some people are more susceptible than others to the metabolic effects of soybean oil.

The study builds on earlier work by UCR researchers linking soybean oil to weight gain. “We’ve known since our 2015 study that soybean oil is more obesogenic than coconut oil,” said Frances Sladek, a UCR professor of cell biology. “But now we have the clearest evidence yet that it’s not the oil itself, or even linoleic acid. It’s what the fat turns into inside the body.”

Linoleic acid is converted into molecules called oxylipins. Excessive consumption of linoleic acid can lead to increased amounts of oxylipins, which are associated with inflammation and fat accumulation.

The genetically engineered, or transgenic, mice in the study had significantly fewer oxylipins and showed healthier livers despite eating the same high-fat soybean oil diet as regular mice. Notably, they also exhibited enhanced mitochondrial function, which may help explain their resistance to weight gain.

The researchers narrowed the obesity-linked compounds down to specific types of oxylipins derived from linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid, another fatty acid found in soybean oil. These oxylipins were necessary for weight gain in regular mice.

However, transgenic mice on a low-fat diet also had elevated oxylipins without becoming obese, suggesting that the presence of these molecules alone isn’t enough, and other metabolic factors likely contribute to obesity.

Additional analysis revealed that the altered mice had much lower levels of two key enzyme families responsible for converting linoleic acid into oxylipins. Notably, the function of these enzymes is highly conserved across all mammals, including humans. Levels of these enzymes are known to be highly variable based on genetics, diet, and other factors.

The team also noted that only oxylipin levels in the liver, and not the in the blood, correlated with body weight. This means common blood tests may not reliably capture early metabolic changes linked to diet.

Soybean oil consumption in the U.S. has increased five-fold in the past century, from about 2% of total calories to nearly 10% today. Although soybeans are a rich source of plant-based protein and their oil contains no cholesterol, the overconsumption of linoleic acid, including from ultra-processed foods, may be fueling chronic metabolic conditions.

Additionally, despite the lack of cholesterol in the oil, the UCR study found that consumption of soybean oil is associated with higher cholesterol levels in mice.

The researchers are now exploring how oxylipin formation causes weight gain, and whether similar effects occur with other oils high in linoleic acid, such as corn, sunflower, and safflower.

“Soybean oil isn’t inherently evil,” Deol said. “But the quantities in which we consume it is triggering pathways our bodies didn’t evolve to handle.”

Though no human trials are planned, the team hopes these findings will help guide future research and inform nutrition policy.

“It took 100 years from the first observed link between chewing tobacco and cancer to get warning labels on cigarettes,” Sladek said. “We hope it won’t take that long for society to recognize the link between excessive soybean oil consumption and negative health effects.”

(Cover image: Thai Liang Lim/iStock/Getty)