Robert Cumming has worked in many mediums over the course of his career as an artist. With roots in painting and sculpture, Cumming shifted his focus to photography in the 1970s before returning to other artistic practices.

But it’s his brief stint in photographic arts that most intrigued UC Riverside alumna Sarah Bay Gachot ’12, curator of “Robert Cumming: The Secret Life of Objects.” On view at the California Museum of Photography Sept. 26 - Feb. 2, 2020, it is the first major museum survey dedicated to Cumming’s photographic projects in nearly 20 years.

Gachot, who graduated with a master’s degree in art history, was a research assistant at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art when she discovered Cumming’s work, noting she was immediately drawn to his photography and decided to make it focus of her master’s thesis. She went on to write a book about Cumming’s photographic work, “Robert Cumming: The Difficulties of Nonsense,” as well as develop “The Secret Life of Objects,” first debuting at New York’s George Eastman Museum in 2017.

“I just thought his work was so funny,” Gachot said. “He was really kind of playing with the camera and using it in a way that was different than a lot of people at the time . . . He was making these really fine prints, but always referencing how the mechanics of the camera work and why that would mess with your perception and make you see things in a new way.”

Most of the photographic work featured in “The Secret Life of Objects” was produced by Cumming in Southern California in the ’70s following his move to Los Angeles. Beginning with his earliest images, mostly traditional nudes taken while he was learning to use a camera, the exhibition traces Cumming’s shift to objects as his subject and his exploration of the inherent power objects possess once photographed.

“Making a photograph of anything kind of locks it in place and it becomes something new because of that,” Gachot said. “You no longer have power over it — you can no longer pick it up or see the back of it . . . it sort of takes on this life of its own.”

Cumming’s sharply detailed imagery, presented as 8-by-10 prints, are simultaneously hyperreal and absurd, calling attention to photography’s ability to record the truth of only a single subjective perspective and how easily that truth can be manipulated.

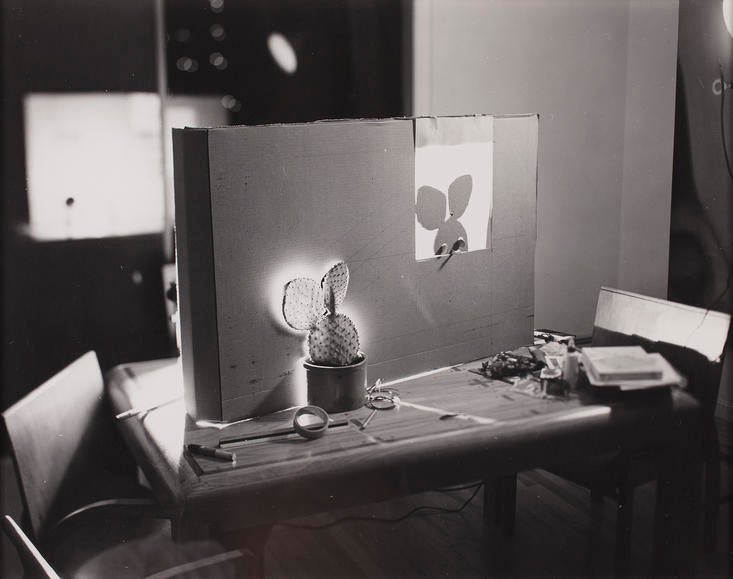

Stemming from his sculptural practice, Cumming would spend weeks devising elaborate and playful tableaux — a cactus whose shadow is merely a cardboard cutout; a chair and bucket mid-tilt held static by wiring — images which would appear visually accurate if not for the tools and apparatus left in frame, or the alternate perspectives offered in diptychs that expose the trickery.

The exhibition also presents sketches of Cumming’s intricate setups as well as a selection of his work in other mediums, including sculpture and mail art, providing a survey of what led up to and fueled his photographic practice and how his work was later informed by this exploration of objecthood and visual deception.

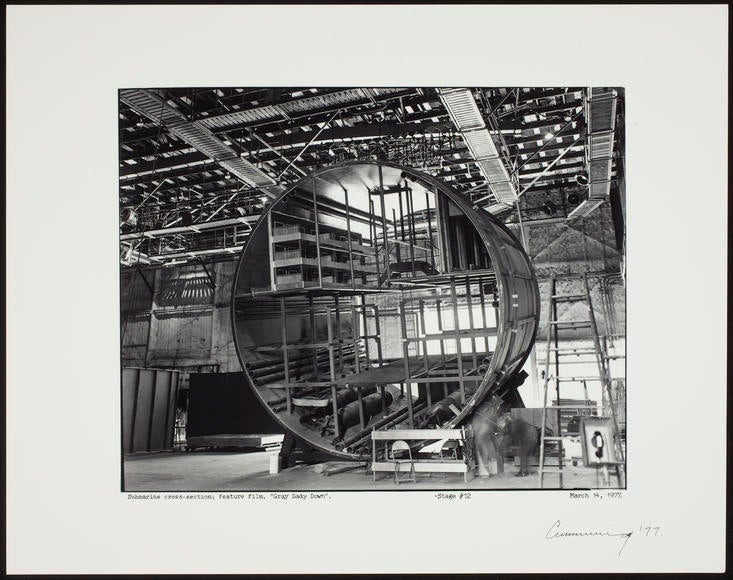

Toward the end of the ’70s, Cumming moved from photographing scenes of his own construction to movie sets on a Hollywood backlot, including a large-scale cross-section of a prop submarine, punctuating his interest in the tension between truth and fiction, and the capacity for imagery to reframe reality.

Cumming’s interest in nautical architecture is also a focus of the exhibition. The artist, whom Gachot said has been working for several years on a book about the subject, became obsessed with finding and photographing buildings with ship-like qualities throughout the U.S. and around the world — buildings with porthole windows or features that mimicked bows and sails, or in some cases, shaped entirely like a boat. She equates this practice with the absurdity and humor of his other photographic subjects, with few things being more illogical than a boat permanently perched on land.

“He likes that people are willing to have absurd ideas and execute them, kind of like he did with his absurd setups in his studio that he would photograph,” Gachot said. “His work has always been about absurdity, and he’s particularly adept at finding absurdity in the real world.”

Although Gachot believes Cumming’s photography has been underrepresented, the influence his style and subject matter have had on contemporary photographers is evident, she said. Cumming’s fascination with photography’s ability to depict and deceive has only become more relevant in a progressively image-saturated world, with the veracity of photographs growing more tenuous as photo manipulation technologies continue to expand.

“The ideas that he was grappling with and exploring about perception and the camera — how people see and how the camera changes what you see — is such a current issue in photography today,” Gachot said. “The whole field of art photography has been expanded because of that, out of the realm of just making a beautiful image and into the realm of really conceptual issues that can also be extremely interesting to look at, which is what he always succeeded in doing.”

A reception for “The Secret Life of Objects” will be held Oct. 5 from 6-8 p.m. at UCR Arts, downtown Riverside. For more information, please visit the UCR Arts website.

Header Image: "Reverse Refraction," 1974. Inkjet print. Courtesy of the artist. © Robert Cumming