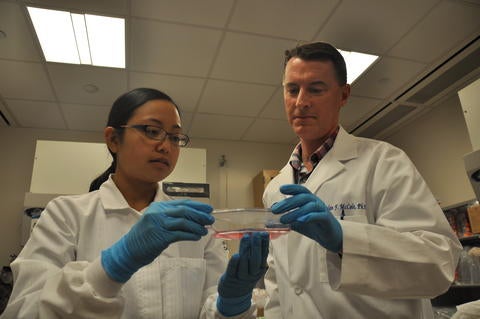

A team of researchers led by biomedical scientist Declan McCole at the University of California, Riverside, has found that the drug tofacitinib, also called Xeljanz and approved by the FDA to treat rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis, can repair permeability defects in the intestine.

“Our work could help improve identification of patients who will be better responders to this drug,” said McCole, a professor of biomedical sciences in the School of Medicine.

Study results appear in the Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis.

Affecting roughly 1 million Americans, ulcerative colitis, an inflammatory bowel disease, is a chronic disease of the large intestine, in which the lining of the colon becomes inflamed and leaky.

A single layer of cells that plays a critical role in human health, the intestinal epithelium provides a barrier while also allowing nutrient and water absorption. Intestinal epithelial cells are critical for regulating immune function, communicating with the intestinal microbiota, and protecting the gut from pathogen infection — all of which critically depend on an intact epithelial barrier. The body’s largest pool of immune cells can be found directly beneath the epithelial cell layer.

The current study is a follow-up to two recently published studies from McCole’s lab. In the first study, published in December 2019, the researchers used a cell culture model system to show that tofacitinib can directly act on epithelial cells that line the gut to correct defects in the barrier properties of these cells that occur in inflammation. The second study, published in July 2020, showed a loss-of-function mutation in the gene “protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor Type 2,” or PTPN2, disrupted normal beneficial interactions between epithelial cells and macrophages — a type of white blood cell that constitutes a considerable fraction of intestinal immune cells — and increased gut leakiness.

In the new study, the authors show tofacitinib can reverse gut leakiness in mice caused by loss of PTPN2 activity. Until now, the effects of tofacitinib on intestinal barrier function in an animal model were largely unknown.

McCole explained that increased intestinal permeability — or leakiness — is a feature of inflammatory bowel disease and plays a critical role in promoting inflammation. His team also tested tofacitinib in a system where PTPN2 expression was reduced in human intestinal epithelial cell lines and macrophages that were then cultured together to study the effects on epithelial permeability. The team also studied mice that had increased gut leakiness resulting from removal of PTPN2 only in macrophages. The researchers found tofacitinib repaired inflammation-induced permeability defects in both the cell culture system and in mice.

“Patients with the loss-of-function mutations in PTPN2 have an increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease,” McCole said. “Our work improves our understanding of how this drug is useful for treating ulcerative colitis and suggests that patients with loss-of-function mutations in the PTPN2 gene may have a better response to tofacitinib. This could help with improved targeting of drug treatments to specific groups of patients.”

McCole was supported in the study by co-first authors of the manuscript, postdoctoral researcher Marianne R. Spalinger and graduate student Anica Sayoc-Becerra, third-year UCR medical student Christ Ordookhanian, graduate student Vinicius Canale, lab manager Alina N. Santos, former graduate student Stephanie J. King, assistant project scientist Moorthy Krishnan, and associate professor Meera G. Nair at the UCR School of Medicine; and Michael Scharl at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Swiss National Science Foundation, and Pfizer Inc., which makes tofacitinib.

The title of the research paper is “The JAK inhibitor tofacitinib rescues intestinal barrier defects caused by disrupted epithelial-macrophage interactions.”