Sally Reyes grew up without shoes. She walked with bare feet through rough terrain, mud, and Belize’s hot dirt roads.

She became the first of 15 siblings to graduate from high school and obtain an associate’s degree. That landed a teaching job in Belize, where she taught for 12 years before coming to the United States in 1979. She left an unhealthy relationship and sought a better life for herself, two young daughters, and the baby boy she was expecting.

Two years after Sally’s arrival, she sent for the girls. One of them was then-7-year-old Deidre Lynn Reyes, who in June becomes the family’s first to obtain a bachelor’s degree from UC Riverside. She’s majoring in public policy and will join the master’s in public policy cohort at UCR in the fall. Her grade point average is set at 3.56.

“My mother is my hero, I wouldn’t be who I am if it wasn’t for her,” said Reyes, 46, of mom Sally Reyes, 71. Reyes is a self-described single mother of four, domestic violence survivor, immigrant, disabled student, transfer student, and honors scholar.

At some point, Reyes also experienced food and housing insecurity, forcing her to live in a motel for two months and postpone graduation by a quarter. She is now at an apartment with her daughters, making final plans for June’s commencement.

“The entire inspiration for going back to school — at 42 years old — was my children,” Reyes said. “I told myself, ‘let’s see what dedicating yourself to school looks like because what you have been doing hasn’t worked.’ My children are my inspiration. I want to show my children that I am a dedicated, determined scholar who is resilient. My goal is to change our narrative from victims to conquerors, because I made a promise to them that I will pull us out of our current income, education, and living situation.”

When Reyes enrolled at Mt. San Jacinto College, she failed her math assessment and while a taking remedial course, her professor noticed Reyes was struggling with basic math. She was soon diagnosed with a cognitive processing disorder in 2017. She connected with tutors and the college’s Disabled Students Programs and Services stepped in to provide a quiet room and additional time for testing.

Growing up in South Central Los Angeles, hanging out with the wrong crowd, ditching school, taking menial jobs, becoming a teen mom, experiencing poverty and domestic violence, wrestling with her identity as an Afro-Latina — all made her want to major in public policy.

She wants to contribute to solving food and housing access, as well as addressing homelessness. A few times a year she gathers snacks and hygiene items to assemble kits in one-gallon Ziploc bags to distribute to Riverside’s homeless.

On campus she is often on student panels and has been involved in more than a dozen student groups, including the university’s student parent group, R’Kids.

Upon her master’s graduation in 2023, she is considering running for Riverside City Council.

On a recent weekday, Reyes visited her mother Sally, who lives five minutes from the studio apartment where Reyes grew up in Los Angeles. Reyes also stopped by to show her youngest daughter, Kaylynn Coleman, 7, the tan, three-story edifice where she used to play when she was Kaylynn’s age. In that apartment, Reyes and her younger sister converted the closet into their safe haven. They shared the closet until the end of middle school.

“It’s incredible, but that was our room until we outgrew it and moved to a one-bedroom duplex down the road,” said Reyes, the memory now provoking laughter. At times they had no electricity. Other times the apartment was filled with friends and new arrivals from Belize. “I don’t know how we did it. My mom helped everyone who came to town, and made sure that they were fed, and had a place to sleep in our tiny crowded studio apartment. And in spite of our circumstances, we were still better off here in America than in Belize.”

Sally Reyes purchased a chalkboard and taught the girls English for a few weeks before sending them to school.

“I was anal about grammar and slang,” Sally said. “I was a teacher in my country, I couldn’t let my children speak like that.”

Reyes picked up the language, primarily motivated to attend elementary school like her cousins because they returned with a sack lunch that included a tiny milk carton — a then-completely foreign way of drinking milk, Reyes said. In elementary school the kitchen staff needed a student helper and Reyes volunteered. She got extra food and sometimes brought it home. She discovered “slimy peaches in syrup … yuck!” and hamburgers.

At the apartment she picked up a Bettye Crocker cookbook and learned to cook. She learned to bake brownies and sold each square for 75 cents each to the neighborhood kids.

Two years before Sally sent for her daughters, she too found ways to make ends meet and save money to bring her girls. She worked in a jewelry store, then accounts payable for a construction company, and eventually retired as a finance administrator with an L.A. County union.

“Those two years without my girls were hard,” said Sally, sitting in her modest 1912 front porch, surrounded by oregano plants and roses. Her light green eyes swell with tears. “Many days I would miss my bus. I would stand at the bus stop like a zombie. My mind was in Belize, wondering if my kids had eaten already.”

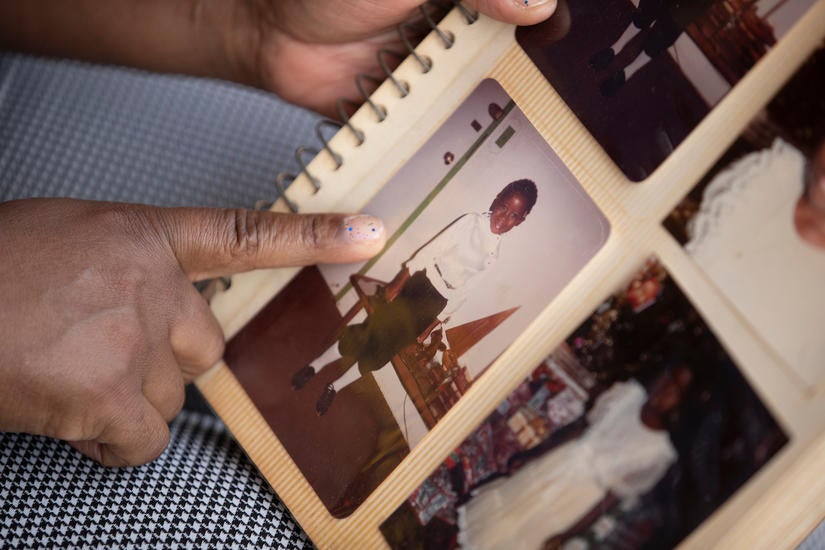

Arriving in L.A. and hugging Sally was a huge relief, said Reyes, gesturing to her mother’s weathered 40-year-old photo album, showing a picture of her and her sister dressed in black-and-white knickers suits. It was the day of their arrival. The family became naturalized U.S. citizens thanks to then-President Ronald Reagan's 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act.

“Being here was both scary and an adventure,” Reyes said. Back in Central America they lived in a stilt house, the ocean was their front yard and fruit trees were at a hand’s reach. Los Angeles was a gray field of concrete.

Sally’s story is closely knit to Reyes’ own. When Reyes had no money, she thought of her mother’s sacrifices to raise three kids.

“Deidre will do anything to make it happen; no job is too menial for her,” Sally said. “I admire her for that. She stumbles and gets back up. Now she’s getting A’s in college, I can’t believe it’s the same high school girl who left my house!”

For Reyes, one of the larger obstacles this past year was living in a Quality Inn for two months; it was December 2020 and she did not have Christmas presents for Kaylynn.

“Every single day I felt like I was going to fall off, I just cried at night,” Reyes remembers. “I was ashamed, how could I end up homeless at my age? I went to get food from the R’Pantry.”

When staff at the School of Public Policy found out, they pooled resources. They delivered gift cards to nearby restaurants, snacks, supplies, utensils, a miniature Christmas tree, and gifts for everyone.

“We didn’t go hungry because of the incredible support we received from UCR’s faculty, staff, R’Pantry, and the School of Public Policy,” Reyes said. “I have to dig deep to pull up, finish strong. I can’t stop, I can’t afford to stop. This is me. It’s my truth. I’m not ashamed, it’s what I’ve experienced and it’s my personal journey.”

It’s a journey Sally Reyes began long ago. A few years ago, Sally bought her first pair of Christian Louboutin pumps to go with her pink, yellow, or flowery Sunday dresses. Her friends mocked her for buying $600 shoes.

“Who are these people who criticize me without knowing my story?” Sally said, recounting the story in front of her daughter. “A mother’s job is never done. I am a mother for life. Coming to this country was the best decision of my life. Look at my child now.”