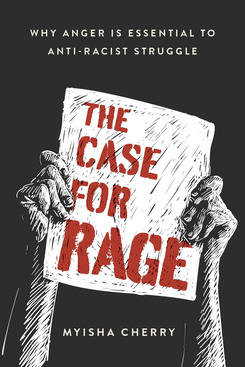

Anger at racial injustice is a powerful motivating force for social justice and should be acknowledged and cultivated as such, argues Myisha Cherry in her new book, “The Case for Rage: Why Anger is Essential to Anti-Racist Struggle” (Oxford University Press, 2021). Cherry, an assistant professor of philosophy at UC Riverside, is interested in moral psychology and social and political philosophy, specifically, the role of emotions and attitudes in public life. Her books include “The Moral Psychology of Anger,” co-edited with Owen Flanagan (Rowman and Littlefield, 2018) and “Unmuted: Conversations on Prejudice, Oppression, and Social Justice” (Oxford University Press, 2019). She also hosts the UnMute Podcast, where she interviews philosophers about current social and political issues.

Q: Your book discusses five types of anger, four of which are not productive for social justice struggles. Can you talk about the fifth type of anger that forms the subject of your book?

Not all anger is created equally. In the book I explain why rogue, wipe, ressentiment, and narcissistic rages are not helpful for social justice struggles. However, there is an inclusive anger, based on the premise that one is not free while others are unfree, that targets racist beliefs, expectations, policies, and behaviors and can be used for social change. This anger can be mistakenly lumped into the same category with other, more destructive types of anger, missing its potential.

I call this anti-racist anger “Lordean rage” after an essay by Black feminist poet, writer, and activist Audre Lorde.

Lorde wrote that anger is an appropriate reaction to racist attitudes and actions. Anger at racism, when paired with the desire to alleviate oppression, is an essential tool for honest communication among activists and for dismantling structures of oppression.

Lordean rage aims for this kind of change — not destruction of the good or elimination of the other, but change in racist beliefs, expectations, policies, and behaviors that shape and support white supremacy. This anti-racist rage can be used to engage in action that brings about such a change.

Like other sorts of anger, anyone can experience Lordean rage. However, those to whom this feeling comes most easily or most frequently are the oppressed, especially those at the intersection of several forms of inequality, such as women, queer, or poor people of color.

Q: When is Lordean rage appropriate, and when is it not appropriate?

Lordean rage can be morally appropriate when it respects the humanity of the wrongdoer and aims to create a better world rather than tear the wrongdoer down in the name of virtue signaling.

In other words, if you are feeling rage against injustice and you aim that rage in a way that is productive and in good faith, rather than just at making a provocative statement to portray yourself in a certain light — righteous, fearless, politically active, and so on — that rage is morally appropriate.

When Lordean rage is in response to a lone, isolated incident, is directed at scapegoats, or aims to eliminate the other instead of unjust laws, practices, or attitudes, it becomes morally inappropriate.

Q: What are some examples of effective and morally appropriate Lordean rage?

The protests that swept the nation following the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in the summer of 2020 are examples of effective, morally appropriate Lordean rage.

So are the 2015 student protests at Yale, where a dispute over racially insensitive Halloween costumes brought years of racist practices and attitudes at the university to a head, and at the University of Missouri at Columbia, where racist slurs hurled at a Black student ignited the fury of students who had long been angry at the administration for responding inadequately to this sort of behavior for many years.

When the cause and the target are racism, feeling rage makes sense. Such rage against racism — rage like these students felt, rage like protestors in a long list of uprisings against racism before and since these incidents have felt — is fitting, appropriate, and correct.

Q: What’s the role of white allies in forwarding anti-racist causes?

White “rage renegades” who feel anti-racist anger sometimes make the mistake of thinking that because they are also angry, they understand the experiences of people oppressed by white supremacy. In their activism, white allies must listen to and place in the foreground the lived experiences of Black people and other people of color.

Because the anger of white people is usually given more credibility than the anger of Black people, white allies often expect that their anger at racial injustice matters more. There is a danger to assume that Black lives only matter because white people say they do, and of “grandstanding” by emphasizing or exaggerating white anger on social media.

When the focus becomes all about the rage that good white people have against racism rather than the racism that needs to be fought against, then injustice gets ignored.

White allies should amplify the Lordean rage of people of color, not appropriate it for their own reasons.