Michael “Mike” Ryan Davis, often revered as “brilliant,” a “North Star,” and an “enemy of the state,” died on October 25 at his San Diego home. He was 76.

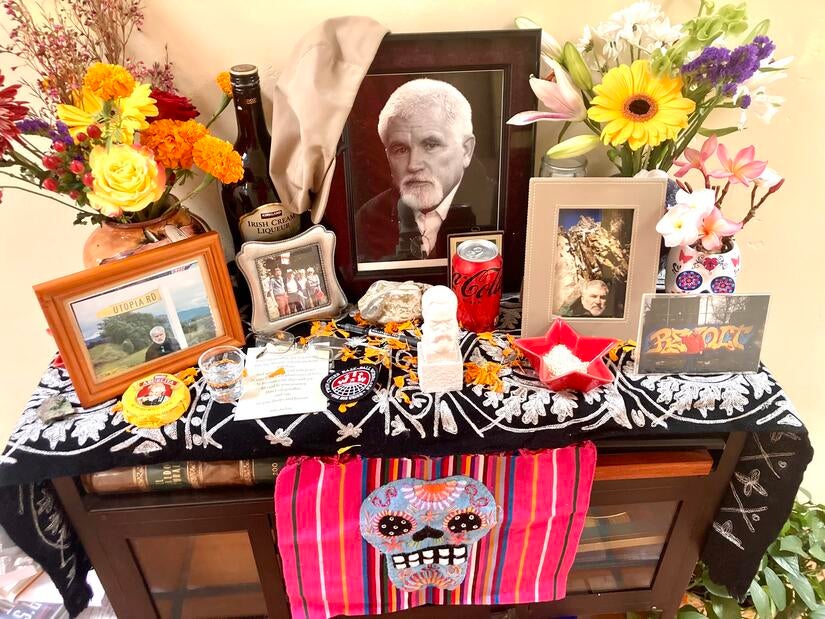

Davis had been battling esophageal cancer. His publishing house, Verso, made the announcement on October 26. Since then, remembrances have been pouring in social media platforms and national and international media outlets. Davis’ partner, Mexican artist Alessandra Moctezuma, posted photos on her Instagram, honoring him with a Día de los Muertos, a Day of the Dead altar.

Davis is the author of more than a dozen books, including his best-known works, “City of Quartz: Excavating the Future of Los Angeles” and “Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World.” His work made him a leading writer, political activists, urban theorist, and historian influenced my Karl Marx theories and philosophies.

He first joined UCR’s Department of Creative Writing in July 2008 and retired eight years later. He remained a distinguished professor emeriti until his death. In 2020 he was awarded the Cultural Freedom Prize by the Lannan Foundation, he was among three recipients of the 2020 prize alongside political activist and author Angela Davis and prison abolitionist and scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore.

Davis was born in Fontana but lived in San Diego for most of his life. His heart always remained in the Inland Empire, he said in a 1998 interview with The Sun.

In July he was interviewed by Los Angeles Times. During that conversation Davis recalled UCR students and the time he spent talking to them about the changing times that threatened their political, social, and economic rights.

All the memories shared by journalists, former students and faculty, are appreciated, Moctezuma, a professor of fine art, museum studies, and gallery director at San Diego Mesa College, said via email.

“It’s lovely to see all of these remembrances and tributes,” Moctezuma said. “I know Mike would be very appreciative too.”

At UCR, faculty shared their memories of Davis:

“I met Mike when he was at UC Irvine. I audited a class he was teaching. His knowledge of history and place was vast and complex, and he was so generous with his time and expertise. He made me feel proud of being from the Inland Empire.”

— Alex Espinoza, associate professor and Tomás Rivera Endowed Chair of Creative Writing

“I once took a quiet, unsuspecting graduate student down to spend a day with Mike in San Diego. After showing us his Pleistocene rock collection, his impressive array of Soviet posters, serving us goat that he had cooked, and convincing my student that the Mormons are the last communists in America, Mike drove us to a cult, a Chaldean Iraqi lunch (where he knew everyone), a truck stop on the eastern outskirts of the city where a unionist revolt had taken place in the Sixties (and where we picked up sandwiches), and, finally, a remote, cactus-covered mountain on the border with Mexico, where, bare-footed, he ran to the summit (with us lumbering behind him) while declaiming into the desert air an entire volume of Freud, verbatim.

This set the tone for all my sojourns — pilgrimages, in my heart — down to see Mike. They were always ten-hour days at least — ten hours of being charmed, riveted, and enchanted by a man who was enchanted with a world that he, more than anyone, knew was wildly, gloriously, perfectly imperfect. He devoted his days, all his life, to getting to know that strange place.

My own enchantment with Mike began in 1989 in graduate school at CalArts — where he gave us the manuscript chapters of “City of Quartz” as he was writing them and took me and few other students to all his secret places in Southern California (well, he saved a few for himself) —and continued through his years at UCR and beyond. Mentor, colleague, friend, hero. He showed me how a person might live nobly amid a human realm that was too often ignoble.

We often dreamed about taking trips together. One was scrambling up the steep north face of Mt. San Jacinto (the tallest urban mountain on the continent, Mike liked to remind me), which involved illegally sneaking across a privately-owned alluvial fan, and negotiating two, near-vertical miles of boulders infested with rattlesnakes, and then navigating slippery ice. I asked Mike whether he would do it barefoot. Mike sometimes liked to let silence answer for him: a mischievous gleam rose to the surface of his eyes, and then he broke out into a smile. Another trip we often considered was driving up a certain, forgotten backroad that followed a major faultline and hadn’t changed since Mike was in his youth — “Pure California gold,” he told me. We never got to it, but in his last month I was able to tell him that I will do it in his honor. He replied: “I can’t tell you how much this means to me or how tickled I am when I visualize you cruising the tectonic plates.” And then he added, “Say hello to James Dean for me.”

— Andrew Winer, associate professor of creative writing. Winer was instrumental in bringing Davis to UCR. They knew each other for 33 years.

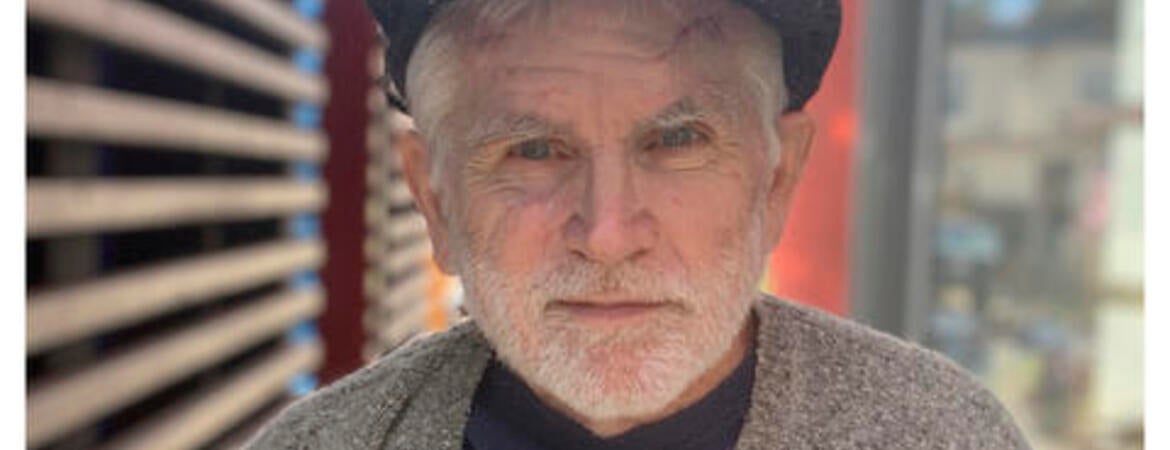

Header image: Late author Mike Davis. Photo by Cassandra Davis.