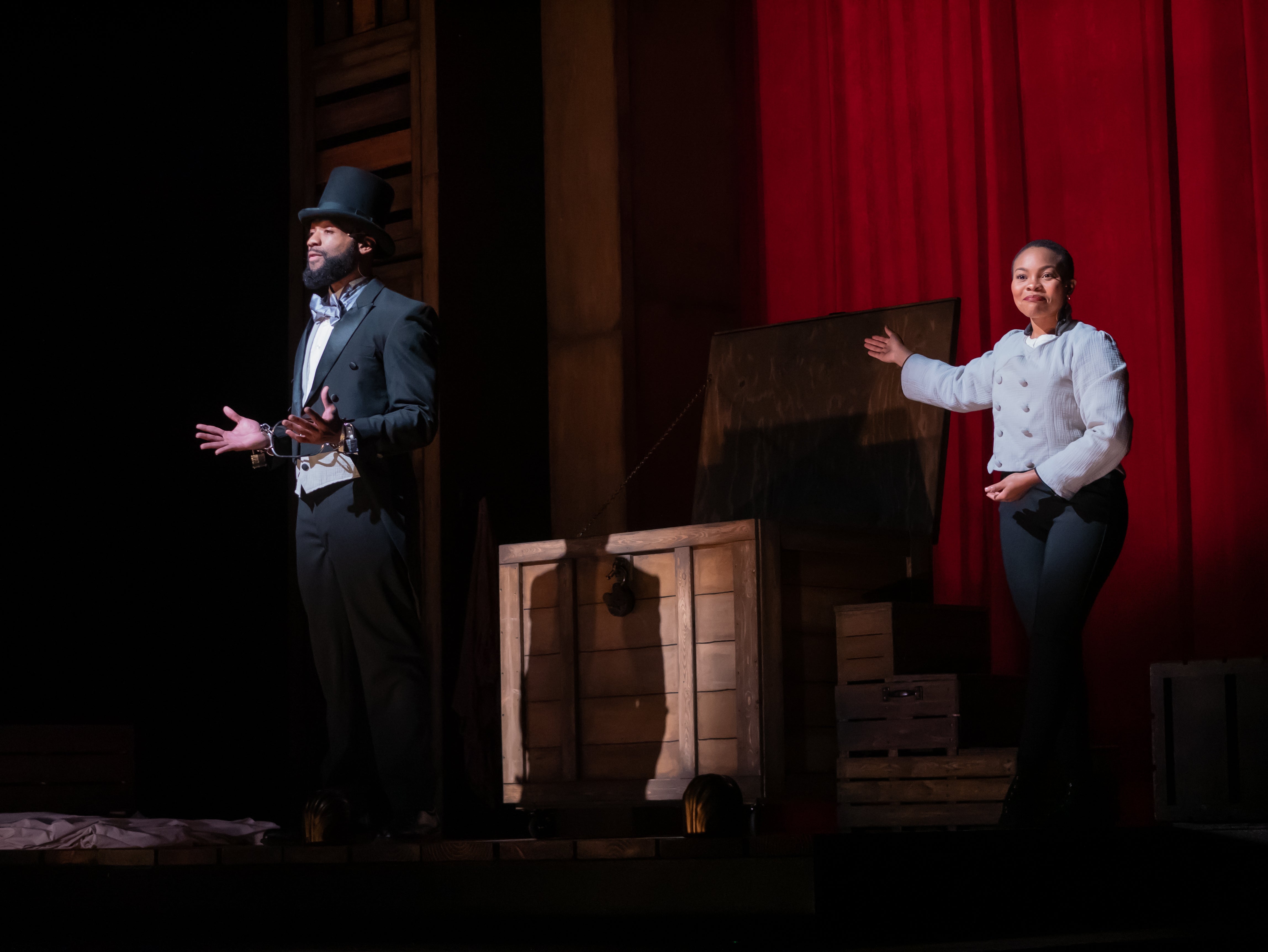

A mist shrouds the stage, and the angled light creates shadows and mystery. It could be dawn or dusk. At center stage sits a large wooden box with a lock hung on the hasp as if ready for an escape artist to perform his act. Crates, a lamp, and other objects give the impression of a loading dock. The wooden slats of a box make up the background. Beyond the background, a screen to project silhouettes, a popular Antebellum South artform.

A character, Spirit, appears at the edge of the stage noticed only by small movements and a sprite’s smile. She glides onto the stage and sets about rearranging the props. She hums softly and is playful as she brings out a set of shackles, removing the locks as a magician’s assistant would do. The big box jiggles. She regards it, concerned. Thunder breaks the stillness. The house lights go down. Henry “Box” Brown appears on stage. “Blackbox” opens.

Rickerby Hinds, a professor in the Department of Theater, Film and Digital Production at the University of California, Riverside, has adapted the life of Henry “Box” Brown, a magician who escaped slavery and became a performing abolitionist, into a unique and powerful play. Hinds insists on “adapted” because much of the text is Brown’s own words. “Blackbox,” commissioned by Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., follows Brown’s escape to Philadelphia from Virginia when, with assistants, he shipped himself in a 3 feet long by 2 feet wide and 2 feet tall box.

At its heart, “Blackbox” is a magic show. A man disappears in one place and reappears in another — a classic illusion. Throughout, we watch Brown perform magic in his pain and gain confidence to stage his greatest performance, his escape to freedom. During his research, Hinds discovered a magician who possesses a list from Brown’s act. Hinds will incorporate some of those illusions in future performances.

In his “epic poem,” Hinds combines a range of performative styles across seven scenes. The dramatic monologue becomes spoken-word poetry, a political speech, a classroom lecture, a sports broadcast, gospel, and a fervent sermon by Nat Turner accompanied by Spirit as she sings with mesmerizing power. The sermon works in juxtaposition with the words of slaveholding Christians justifying the horrors of slavery with scripture, including the Methodist minister who separated Brown from his wife and children, vividly enacted with paper dolls.

The choreography includes TURF Dance — a street dance — and Butoh, a Japanese dance. At first thought, the Japanese dance wouldn’t seem to fit, but it does. The graceful and fluid movements that rise from the floor “like smoke from burnt grass” and “expressing a world underneath the ground” hold symbolic resonance with TURF. As an art form born from war and nuclear devastation, it creates a parallel with TURF Dance’s expression of systemic racism and police brutality.

Set in Brown’s box, the silhouettes of people and landscapes beyond the slats create the illusion we are traveling with Brown through time and space. As the painter Kara Walker says, silhouettes give “a lot with very little information.” Hinds said setting the play inside the box – in Brown’s mind – gave him a creative freedom to blend the different styles that a realistic dramatic narrative couldn’t provide.

“Blackbox” opened at UCR’s University Theater in October and has completed its UCR run. Hinds’ ambition is Riverside-to-Broadway. It next will be performed as part of the 2024-25 inaugural Lincoln Legacy Commissions at the historic Ford Theatre. After that run, Hinds hopes to take it to Broadway.

Hinds is currently working on a play about the life of Frederick Douglas.