With Donald Trump and other right-wing politicians increasingly using dehumanizing rhetoric to stigmatize immigrants coming to our nation's borders, doctors and other health officials should prepare for the resulting health consequences.

Such is the message of a “Viewpoint” article co-authored by UC Riverside professor Bruce Link and published Monday, July 1, in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Link and his co-authors quote Trump as saying, “No, they’re not humans. They’re not humans. They’re animals,” at a recent rally in reference to immigrants wanting to cross U.S. borders.

When top political leaders engage in such rhetoric — rather than condemn it — stigmatization becomes more legitimized and pervasive in society, said Link, a distinguished professor of sociology and public policy, who also teaches at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

The harm goes beyond those seeking entry into the country. It also extends to groups viewed as associated with immigration, such as descendants of immigrants, and to people belonging to ethnic and racial groups with histories of global migration, Link and his co-authors say in the paper.

These groups then face ill health consequences.

Firstly, stigmatization increases stress, which causes or exacerbates a host of physical and mental health problems, including heart disease, gastrointestinal problems, high blood pressure, anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders.

It further makes people less likely to seek needed medical attention.

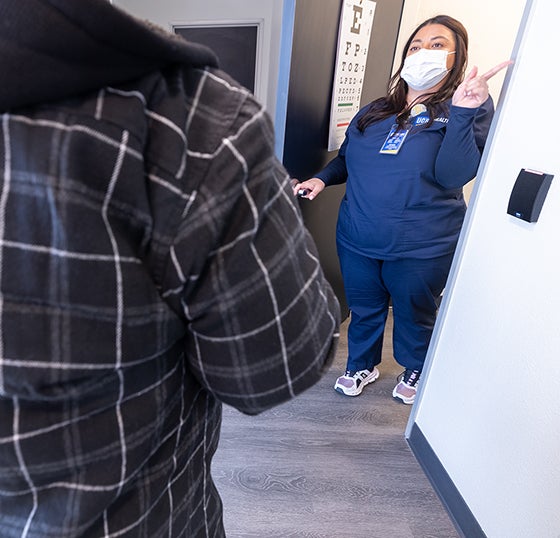

“It inhibits people from feeling comfortable in pursuing things that matter to them and what they need, and one of those things is healthcare,” Link said. “Going to the doctor is a threat because of its connection to an authority. And this really intensifies when you worry that you're going to be treated differently, and negatively.”

Link and his co-authors urge doctors and other healthcare providers to be cognizant of and to better understand these health impacts and fears and concerns of their immigrant patients. They urge providers to work with community groups to make their approaches and facilities welcoming.

Link commended the UCR’s School of Medicine for teaching future doctors to learn about the “upstream situations” of their patients.

“Upstream means things that came before the health problem and that likely contributed to that problem,” Link said. “And that if physicians can learn to identify those things, it changes how they might relate to the person in front of them.”

Because the politicization of immigration is expected to continue, the paper further outlines areas that need research to better understand the costs of migration stigma. Such research should include probes into what extent immigrants lose status and face discrimination, and how much these effects extend to descendants of immigrants and to ethnic groups associated with them.

Researchers should further assess the long-term health consequences of stigmatization as reflected through policies that govern access to healthcare and what structural changes would better serve immigrant populations, the authors assert.

The paper’s title is “The human cost of politicizing immigration: migration stigma, U.S. politics, and health.” In addition to Link, its authors are Lawrence H. Yang, New York University School of Global Health; and Maureen A. Eger, Umeå University, Sweden, and the UC Berkeley Center for Right-Wing Studies.