Chemists have confirmed a 67-year-old theory about vitamin B1 by stabilizing a reactive molecule in water — a feat long thought impossible. The discovery not only solves a biochemical mystery, but also opens the door to greener, more efficient ways of making pharmaceuticals.

The molecule in question is a carbene, a type of carbon atom with only six valence electrons. Generally, carbon is stable with eight electrons around it. With only six electrons, it is chemically unstable and highly reactive. In water, it usually decomposes instantly. But for decades, scientists have suspected that vitamin B1, also known as thiamine, may form a carbene-like structure in our cells to carry out vital reactions in the body.

Now, for the first time, researchers have not only generated a stable carbene in water, they’ve also isolated it, sealed it in a tube, and watched it stay intact for months. This discovery is documented in a paper published last week in Science Advances.

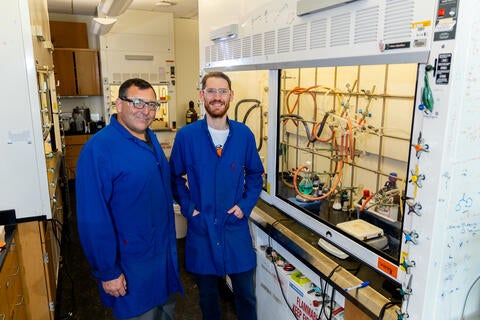

“This is the first time anyone has been able to observe a stable carbene in water,” said Vincent Lavallo, a professor of chemistry at UC Riverside and corresponding author of the paper. “People thought this was a crazy idea. But it turns out, Breslow was right.”

The reference is to Ronald Breslow, a Columbia University chemist who proposed in 1958 that vitamin B1 could convert into a carbene to drive biochemical transformations in the body. Breslow’s idea was compelling, but carbenes were so unstable — especially in water — that no one could prove they actually existed in a biological setting.

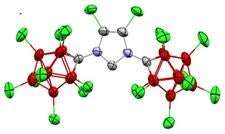

Lavallo’s team succeeded by wrapping the carbene in what he calls “a suit of armor,” a molecule they synthesized in the laboratory that shields the reactive center from water and other molecules. The resulting structure is stable enough to be studied with nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and x-ray crystallography — providing conclusive evidence that carbenes like this can exist in water.

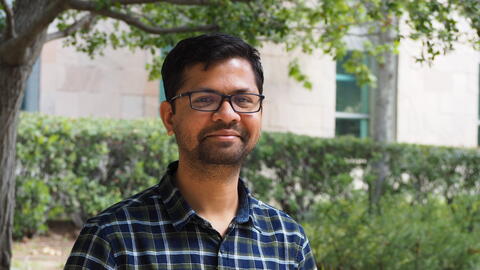

“We were making these reactive molecules to explore their chemistry, not chasing a historical theory,” said first author Varun Raviprolu, who completed the research as a graduate student at UCR and is now a postdoctoral researcher at UCLA. “But it turns out our work ended up confirming exactly what Breslow proposed all those years ago.”

Beyond confirming a biochemical hypothesis, the discovery has practical implications. Carbenes are often used as “ligands,” or support structures, in metal-based catalysts — the chemical workhorses used to produce pharmaceuticals, fuels, and other materials. Most of these processes rely on toxic organic solvents. The researchers’ method of stabilizing carbenes in water could help make those reactions cleaner, less expensive, and safer.

“Water is the ideal solvent — it’s abundant, non-toxic, and environmentally friendly,” Raviprolu said. “If we can get these powerful catalysts to work in water, that’s a big step toward greener chemistry.”

Knowing that such reactive intermediate molecules can be generated and survive in water also brings scientists one step closer to mimicking the kind of chemistry that happens naturally in cells — which are mostly made of water.

“There are other reactive intermediates we’ve never been able to isolate, just like this one,” Lavallo said. “Using protective strategies like ours, we may finally be able to see them, and learn from them.”

For Lavallo, who has spent two decades designing carbenes, the moment is both professional and personal.

“Just 30 years ago, people thought these molecules couldn’t even be made,” he said. “Now we can bottle them in water. What Breslow said all those years ago — he was right.”

For Raviprolu, the discovery serves as a reminder to persevere in scientific research and discovery.

“Something that seems impossible today might be possible tomorrow, if we continue to invest in science,” he said.