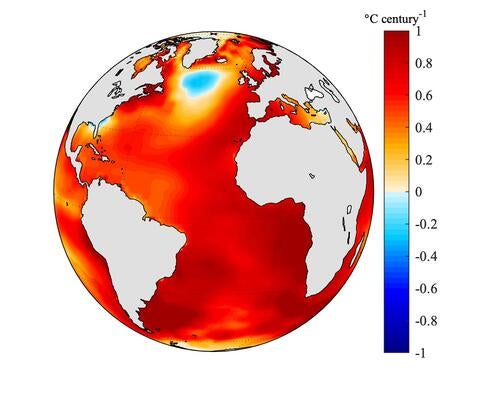

For more than a century, a patch of cold water south of Greenland has resisted the Atlantic Ocean’s overall warming, fueling debate amongst scientists. A new study identifies the cause as the long-term weakening of a major ocean circulation system.

Researchers from the University of California, Riverside show that only one explanation fits both observed ocean temperatures and salinity patterns: the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, is slowing down. This massive current system helps regulate climate by moving warm, salty water northward and cooler water southward at depth.

“People have been asking why this cold spot exists,” said UCR climate scientist Wei Liu, who led the study with doctoral student Kai-Yuan Li. “We found the most likely answer is a weakening AMOC.”

The AMOC acts like a giant conveyor belt, delivering heat and salt from the tropics to the North Atlantic. A slowdown in this system means less warm, salty water reaches the sub-polar region, resulting in the cooling and freshening observed south of Greenland.

When the current slows, less heat and salt reach the North Atlantic, leading to cooler, fresher surface waters. This is why salinity and temperature data can be used to reconstruct the strength of the AMOC.

Li and Liu analyzed a century’s worth of this data, as direct AMOC observations go back only about 20 years. From these long-term records, they reconstructed changes in the circulation system and compared those with nearly 100 different climate models.

As the paper published in Communications Earth & Environment shows, only the models simulating a weakened AMOC generally matched the real-world data. Models that assumed a stronger circulation didn’t come close.

“It’s a very robust correlation,” Li said. “If you look at the observations and compare them with all the simulations, only the weakened-AMOC scenario reproduces the cooling in this one region.”

The study also found that the weakening of the AMOC correlates with decreased salinity. This is another clear sign that less warm, salty water is being transported northward.

The consequences are broad. The South Greenland anomaly matters not just because it’s unusual, but because it’s one of the most sensitive regions to changes in ocean circulation. It affects weather patterns across Europe, altering rainfall and shifting the jet stream, which is a high-altitude air current that steers weather systems and helps regulate temperatures across North America and Europe.

The slowdown may also disturb marine ecosystems, as changes in salinity and temperature influence where species can live.

This result may help settle a dispute amongst climate modelers about whether the South Greenland cooling is driven primarily by ocean dynamics or by atmospheric factors such as aerosol pollution. Many newer models suggested the latter, predicting a strengthened AMOC due to declining aerosol emissions. But those models failed to recreate the actual, observed cooling.

“Our results show that only the models with a weakening AMOC get it right,” Liu said. “That means many of the recent models are too sensitive to aerosol changes, and less accurate for this region.”

By resolving that mismatch, the study strengthens future climate forecasts, especially those concerning Europe, where the influence of the AMOC is most pronounced.

The study also highlights the ability to draw clear conclusions from indirect evidence. With limited direct data on the AMOC, temperature and salinity records provide a valuable alternative for detecting long-term circulation change, and for helping to predict future climate scenarios.

“We don’t have direct observations going back a century, but the temperature and salinity data let us see the past clearly,” Li said. “This work shows the AMOC has been weakening for more than a century, and that trend is likely to continue if greenhouse gases keep rising.”

As the climate system shifts, the South Greenland cold spot may grow in influence. The hope is that by unlocking its origins, scientists can better prepare societies for what lies ahead.

“The technique we used is a powerful way to understand how the ocean and climate systems have changed, and where they are likely headed if greenhouse gases keep rising,” Li said.

(Cover image of Labrador Sea iceberg: GibasDigiPhoto/iStock/Getty)