Scientists have long warned that rising global temperatures would force forest soils to leak more nitrogen gas into the air, further increasing both pollution and warming while robbing trees of an essential growth factor. But a new study challenges these assumptions.

After six years of UC Riverside-led research in a temperate Chinese forest, researchers have found that warming may be reducing nitrogen emissions, at least in places where rainfall is scarce.

The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, are the result of UCR’s collaboration with a large team of graduate students and postdoctoral researchers stationed in China’s Shenyang City. These researchers maintained the infrastructure used to take more than 200,000 gas measurements from forest soil over six years.

The study simulated a 2°C rise in temperature, which is roughly the amount predicted by mid-century. Instead of the expected spike in nitrogen loss, researchers found emissions of nitric oxide dropped 19%, while nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, fell 16%.

“These results flip our assumptions,” said Pete Homyak, UCR associate professor of environmental sciences. “We’ve always thought warming would accelerate microbial processes and release more nitrogen. That can be true in a lab under controlled conditions. But in the field, especially under dry conditions, the microbes slow down because the soils dry out.”

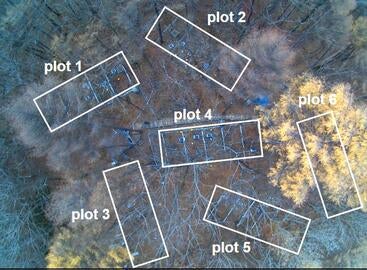

To replicate climate change, the team mounted infrared heaters above forest plots in Qingyuan County, warming the soil from above to mimic atmospheric heat. The site, chosen for its sensitivity to climate variation, is part of a growing network of global forest experiments trying to decode how warming alters ecological cycles.

In the complex drama of climate, soil, and life, nitrogen plays a starring role. Forests are among Earth’s most important natural systems that absorb more carbon dioxide than they emit, also known as carbon sinks. But trees need nitrogen to grow, and if warming strips it from the soil too quickly, forests could become less effective at storing carbon.

“Our concern is about what warming does to the nitrogen cycle, and whether forests will have enough nutrients to keep absorbing carbon as the planet heats up,” said ecologist Kai Huang, first author of the study and a postdoctoral scholar in Homyak’s laboratory visiting from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “This study shows that moisture, not just heat, is key.”

The team’s findings show there is a threshold for the effects they observed. In places receiving less than 1,000 millimeters (about 40 inches) of rain per year, warming tends to dry out soils and reduce gas emissions. But in wetter forests, warming does increase nitrogen loss, just as earlier lab-based models predicted.

“This is a major refinement,” Homyak said. “Climate models that overlook soil moisture are missing a crucial part of the story.”

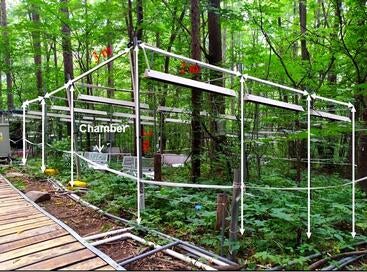

To conduct the study, six forest plots − each 108-square meters − were equipped with automated chambers that opened and sealed to measure gas levels. The effort generated a high-resolution view of how subtle shifts in the environment can ripple through forest ecosystems.

Yet the study also leaves open important questions. Though nitrogen appears to be staying put in the drier forest soil, it did not accelerate tree growth. Ongoing, unpublished measurements indicate that trees in the warmed plots may be growing more slowly than those in control plots, possibly due to drought stress.

“We may not be losing nitrogen to the atmosphere in drier soils, but if trees can’t use it because of drought, that’s another problem entirely,” Huang said.

While the research isn’t a green light for climate optimism, it does offer new clarity. The researchers now believe the interaction of heat and moisture must be modeled together to better predict the future of ecosystems. The team is continuing to track microbial responses, soil chemistry, and forest health in this and other experimental plots worldwide.

“As the planet warms,” Homyak added, “these long-term studies help us fine-tune climate models and better understand how forests will behave in a world that’s changing quickly.”

(Cover image of Qingyuan County forest research site: Kai Huang/UCR)