An experiment in western China over the past four decades shows that it is possible to tame the expansion of desert lands with greenery, and, in the process, pull excess carbon dioxide out of the sky.

The sprawling greening project along the edges of China’s Taklamakan Desert is creating a visible and measurable carbon sink, even in one of the driest places on Earth, according to a study led by scientists at the University of California, Riverside. The project is an example of successful afforestation, which is an effort to plant trees or shrubs on previously barren land.

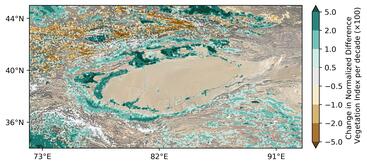

UCR atmospheric physicist King-Fai Li co-authored the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, analyzing multiple years of satellite data over the desert’s rim, where the Chinese government began planting hardy shrubs and trees in 1978 to stop the desert from growing.

For this study, the researchers observed two major indicators of successful afforestation. These include a drop in atmospheric carbon dioxide and a rise in solar-induced fluorescence, a light emitted during photosynthesis, which shows just how much plant life is now thriving in the Taklamakan.

“This is not like a rainforest in the Amazon or Congo,” Li said. “Some

afforested regions are only shrublands like Southern California’s chaparral. But the fact that they are drawing down CO₂ at all, and doing it consistently, is something positive we can measure and verify from space.”

In addition to Li, the research team included atmospheric scientist Xun Jiang at the University of Houston, Earth system scientist Le Yu at Tsinghua University in Beijing, and planetary scientist Yuk L. Yung at Caltech.

The team relied on data from NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO) and the MODIS satellite, which together tracked carbon dioxide concentrations and greenness over the Taklamakan. The OCO satellite revealed a “cold spot” area 1 to 2 parts per million lower in carbon dioxide.

Li said the work provides a rare, long-term case study of desert greening in action. Unlike similar attempts, such as one launched in the Sahara Desert by the United Nations, the Chinese initiative endured. Political stability allowed the project to persist uninterrupted for decades.

medium-sized trees today. (Le Yu/Tsinghua University)

China’s motivations were both environmental and political. Unrestrained desert growth threatened farmland and contributed to instability in western regions, where minority ethnic groups have long clashed with Han Chinese leadership. Reversing desertification was also seen as a strategy for improving agricultural prospects and reducing the nation’s carbon footprint.

The results suggest that afforestation can make a dent in atmospheric carbon, though a modest one. Even if the entire Taklamakan, roughly the size of Germany, were afforested, it would offset only about 10% of Canada’s annual CO₂ emissions, or roughly 60 million tons. For perspective, global emissions are about 40 billion tons per year.

Still, that doesn’t mean the effort is futile.

“We’re not going to solve the climate crisis by planting trees in deserts alone. But understanding where and how much CO₂ can be drawn down, and under what conditions, is essential,” Li said. “This is one piece of the puzzle.”

Water remains the biggest obstacle to increasing afforestation efforts in the Taklamakan and elsewhere. Shrubs planted on the desert’s rim survive only because of mountain runoff that flows down from surrounding highlands. Expanding the project deeper into the desert would require a reliable water source, something in increasingly short supply across the planet.

Several years ago, other research groups noted a curious finding: desert sand itself may physically trap CO₂ through expansion and contraction cycles caused by day-night temperature swings. While this carbon capture mechanism is minor compared to photosynthesis, it may still contribute as much as one million tons of carbon sequestration annually.

Ultimately, the researchers recommend entering into afforestation efforts with full awareness of the benefits and drawbacks. Trees also emit carbon dioxide through respiration, and the net benefit depends on complex factors including soil type, vegetation density, and geography.

But in a world hungry for scalable, low-tech carbon solutions, this project may serve as both inspiration and a proof of concept.

“Even deserts are not hopeless,” Li said. “With the right planning and patience, it is possible to bring life back to the land, and, in so doing, help us breathe a little easier.”