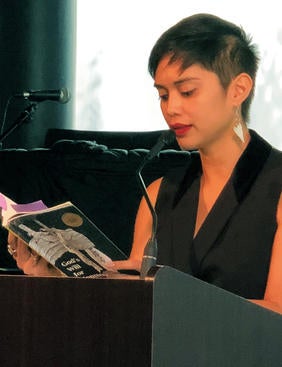

There was a time when Rachelle Cruz, M.F.A. ’12, had all but given up on getting her poetry collection published.

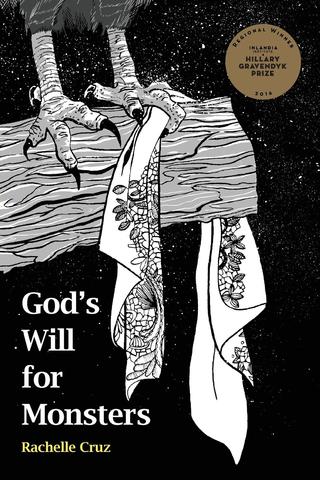

A 10-year labor of love, she recalled sending out “God’s Will for Monsters” 20-25 times before taking a two-year break from her attempts. As a last-ditch effort, Cruz submitted her collection to Inlandia Institute’s second annual Hillary Gravendyk Prize — where it was named the 2016 regional prize winner and subsequently published by Inlandia in February 2017.

Now Cruz, a lecturer in UC Riverside’s Department of Creative Writing, has had her debut collection recognized with a 2018 American Book Award. Given by the Before Columbus Foundation, these honors were created to provide recognition for outstanding literary achievement from the entire spectrum of the nation’s diverse literary community.

“God’s Will for Monsters” is steeped in personal and cultural history. The daughter of Filipino immigrants, Cruz’s poems explore the folklore and customs she grew up with, religion, womanhood, and the lingering effects of colonialism on the Filipino diaspora. The central figure in her collection is the “aswang” — a mythical, shapeshifting creature in Filipino folklore.

“I was interested in the aswang as a shapeshifter and my own identity, as someone who can shapeshift and code switch as well,” she said. “I was thinking about how Filipinos — people — are the number one export in the Philippines. Anywhere you go in the world, you’ll find Filipino labor, primarily female labor, and there’s a sense of shapeshifting there, where they can blend in and adapt and hide.”

Cruz took inspiration from her mother, father, and grandmother who frequently told her stories about the aswang and other Filipino mythical creatures as a child. Later, as she researched the aswang during graduate school, she was troubled by the Eurocentric nature of her findings but heartened by the work of Lynda Barry, Barbara Jane Reyes, and Aimee Nezhukumatahil, all writers of Filipino ancestry, who have reclaimed and reimagined Philippine mythical creatures and the aswang figure.

The work of researcher Carolyn Brewer was also especially influential. Her research traced the origin of the Aswang to pre-colonial Philippines, a time when female village leaders and faith healers were branded as witches or aswangs by Roman Catholic Spanish friars as a way to strip women of their power. Cruz was interested in subverting the idea of the aswang as a monster and reclaiming it as a deeply nuanced, empowered figure, as in her poem, “Calling all the Aswangs of the World!”

“There’s so much division and misogyny in the Filipino community — even by women — and I was really interested in being able to investigate the shames and silences that we’ve carried,” Cruz said.

The prominent role of Catholicism in the Philippines is also a focus of Cruz’s poems, especially in relation to womanhood and her own tenuous relationship with religion. In the poem “How to Marry God,” she examines the ritual of communion.

“I wanted to unlearn some of the violent ways in which Catholicism, in the way I understood it as a child, felt like an oppressive relationship with God and examine the surreal nature of preparing little girls to marry a male God,” she said. “A lot of these poems are wrestling with God. What does this God mean to me? What does it mean to have a relationship with God, and what happens when there is a God that was forced upon you and generations of your family through colonization?”

Cruz makes use of unconventional forms in her poetry, sometimes evoking the voice of controversial Philippine politician Imelda Marcos, presenting other poems as scholarly excerpts and bulletin postings, or relegating her words to footnotes, as in her series of “(sst)” poems — referring to a sharp, whispered “sst” sound used by Filipinos to call someone’s attention.

“I’m really interested in silences, and in a lot of immigrant families there isn’t a lot of direct communication,” Cruz said.

Perhaps the most unique poem in terms of form, “MAXIMUM 25 WORDS” is presented as a series of remittance slips in which Cruz exemplifies life as a “kababayan” — a Filipino living overseas.

“These overseas workers, including members of my family, sent money back home; sometimes the majority of their paychecks,” she said. Sometimes they were the sole benefactors for their families in the Philippines, and as a kid I’m writing these messages out in my mom’s remittance and tax office, thinking like, OK, maximum 25 words. That’s all they had, and maybe that was one of the few points of contact that they had with their families back home. That really struck me growing up — seeing the effects of colonialism and U.S. imperialism on the Philippines. The weight of the remittance slip was just one metaphor for this.”

Cruz hopes “God’s Will for Monsters” will speak to Filipino women still largely underrepresented in literature and media.

“Part of the process was realizing that not everyone is going to be my audience,” she said. “I felt like, why not have a book speaking specifically to brown girls or Filipino girls? I didn’t see that so much growing up.”

Cruz was awarded the Hillary Gravendyk Prize in 2016. She is also a Kundiman fellow and a former PEN America fellow.