Tiny, seemingly harmless ocean plants survived the darkness of the asteroid strike that killed the dinosaurs by learning a ghoulish behavior — eating other living creatures.

Vast amounts of debris, soot, and aerosols shot into the atmosphere when an asteroid slammed into Earth 66 million years ago, plunging the planet into darkness, cooling the climate, and acidifying the oceans. Along with the dinosaurs on the land and giant reptiles in the ocean, the dominant species of marine algae were instantly wiped out — except for one rare type.

A team of scientists, including researchers at UC Riverside, wanted to understand how these algae managed to thrive while the mass extinction rippled throughout the rest of the global food chain.

“This event came closest to wiping out all multicellular life on this planet, at least in the ocean,” said UCR geologist and study co-author Andrew Ridgwell. “If you remove algae, which form the base of the food chain, everything else should die. We wanted to know how Earth’s oceans avoided that fate, and how our modern marine ecosystem re-evolved after such a catastrophe.”

To answer their questions, the team examined well-preserved fossils of the surviving algae and created detailed computer models to simulate the likely evolution of the algae’s feeding habits over time. Their findings are now published in the journal Science Advances.

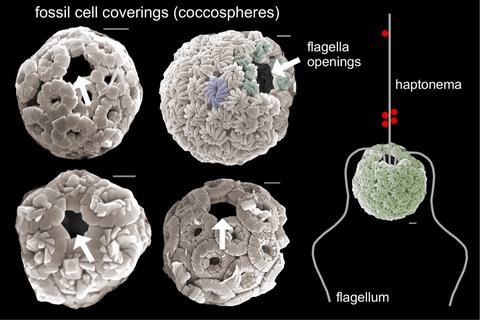

According to Ridgwell, scientists were a bit lucky to find the nano-sized fossils in the first place. They were located in fast accumulating and high-clay-content sediments, which helped preserved them in the same way the La Brea tar pits provide a special environment to help preserve mammoths.

Most of the fossils had shields made of calcium carbonate, as well as holes in their shields. The holes indicate the presence of flagella — thin, tail-like structures that allow tiny organisms to swim.

“The only reason you need to move is to get your prey,” Ridgwell explained.

Modern relatives of the ancient algae also have chloroplasts, which enable them to use sunlight to make food from carbon dioxide and water. This ability to survive both by feeding on other organisms and through photosynthesis is called mixotrophy. Examples of the few land plants with this ability include Venus flytraps and sundews.

Researchers found that once the post-asteroid darkness cleared, these mixotrophic algae expanded from coastal shelf areas into the open ocean where they became a dominant life form for the next million years, helping to quickly rebuild the food chain. It also helped that larger creatures who would normally feed on these algae were initially absent in the post-extinction oceans.

“The results illustrate both the extreme adaptability of ocean plankton and their capacity to rapidly evolve, yet also, for plants with a generation time of just a single day, that you are always only a year of darkness away from extinction,” Ridgwell said.

Only much later did the algae evolve, losing the ability to eat other creatures and re-establishing themselves to become one of the dominant species of algae in today’s ocean.

“Mixotrophy was both the means of initial survival and then an advantage after the

post-asteroid darkness lifted because of the abundant small pretty cells, likely survivor cyanobacteria,” Ridgwell said. "It is the ultimate Halloween story — when the lights go out, everyone starts eating each other."