A UC Riverside-led team is looking at tiny underground microorganisms for a way to prevent a huge problem — Huanglongbing, a disease with no cure that has decimated citrus orchards worldwide.

The disease, also known as HLB or citrus greening, has multiple names but the same ultimate result: bitter and worthless citrus fruits. By some estimates, the end of citrus orchards in California and Florida could amount to $14 billion in lost commercial revenue.

“Often times, it is thought of as an above-ground disease of the fruits, leaves, and stems,” said Caroline Roper, plant pathology professor and director of the new research effort. “However, we have seen the roots of trees decline with infection, and we want to understand why.”

The National Institute of Food and Agriculture has awarded the UCR-led team $10 million over the next five years to investigate the role of soil and root microbes in the disease.

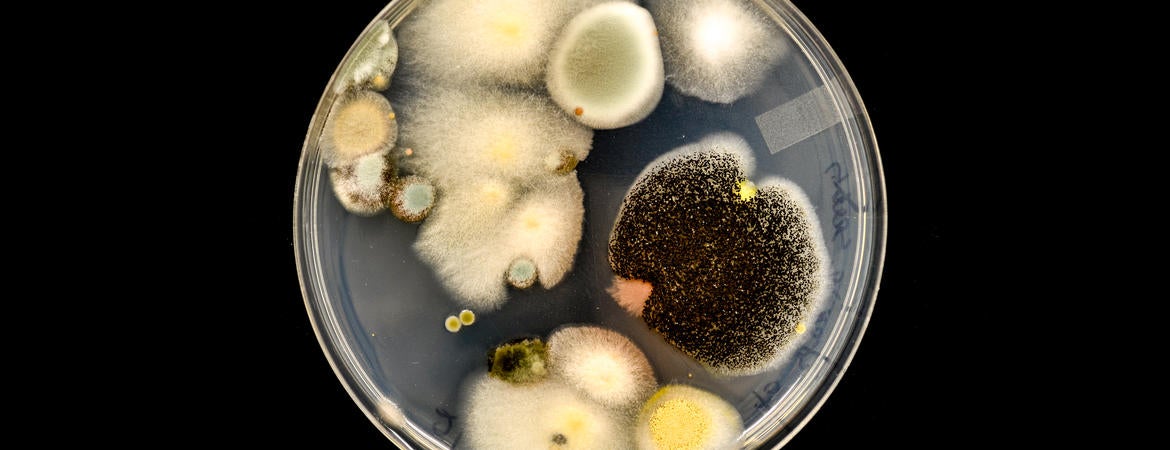

Roper said data from previous studies shows the microbiome of the infected tree — which includes bacteria and fungi as well as protozoa and viruses — plays a role in the disease.

“We have seen a shift in the root microbiome as trees get sicker,” she said.

The microbiomes shift to contain more potentially parasitic organisms that may act as secondary invaders to a tree that is suffering from HLB, according to Roper. The invasion of these root pathogens may be causing trees to die faster when they have HLB.

Part of this new research effort will test whether soil amendments like manure and compost might suppress parasitic microorganisms in the roots as well as the soil, and give the trees more strength to combat diseases including HLB.

In addition, the research team will try to determine the molecular basis of HLB resistance shown by citrus root stocks developed in Florida. They’ll then see how those rootstocks perform in California, which has different soil and climate conditions.

The research team will examine both younger trees, because a lot of citrus growers have had to re-plant their orchards after infection, as well as older trees to see if mature groves can recover.

It will also be important to note how well root stocks from Florida, where there has been a heavy infestation of HLB, perform in California, where much less of the disease has been detected.

“One of the great things about this grant is that we’re able to leverage existing field trials being done by our collaborators in Florida and at the UC’s Lindcove Research and Extension Center in central California,” Roper said. “This may lead to faster results than we’d otherwise have had.”

Collaborators on the project include UC Davis; California State University, Sacramento; the University of Florida; and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service in Ft. Pierce, Florida.