The words written by authors Sandra Cisneros, Linda Hogan, and Ishmael Reed have been stamped in history.

Their literary contributions in fiction, essay, poetry, play scripts, memoirs, or opinion pieces, have made their way into classrooms, conversations, and even the White House. These three literary giants are the honorees of the 2022 LA Review of Books-UC Riverside Department of Creative Writing Lifetime Achievement Award during this year’s Writers Week Festival, happening online Feb. 12 and Feb. 14-18.

“It’s an honor to present this Lifetime Achievement Award to these three fierce writers,” said Allison Adelle Hedge Coke, Writers Week director. “For decades through their brilliantly luminous work, they have contributed to larger societal and political conversations. They have spoken to sheer beauty and shining glory of being from richly familial places, especially as continually complicated by utterly gross inequities for marginalized communities, and they’ve offered powerful statements of what it means to be Indigenous, Black or Latina in the United States and other places. We applaud their love for expression and for teaching us the importance of finding and using our voices. For taking us there.”

UC Riverside’s 45th annual Writers Week Festival is the longest-running free literary event in California. The festival, which will be held virtually on Crowdcast with American Sign Language and closed captioning, features over 40 confirmed authors who will engage with online audiences during the week. Continuing the festival in a virtual space allows for wider audiences; last year’s festival had a record 2,599 seats filled, including campus, local, regional, national, and international participants, Hedge Coke said.

Members of the public are also invited to the free event on Feb. 18 to honor Cisneros, Hogan, and Reed, and to a post-festival ticketed event to celebrate them on Feb. 19.

The festival is welcoming stars from a variety of disciplines, including a newly added Feb. 16 panel, “Story as Medicine,” with Kimberly Guerrero, Elizabeth Frances, and Kalani Queypo, all well-established writers and actors. A storytelling and play performances will also be presented by Richard Van Camp, Isabella Madrigal and Sophia Madrigal.

Other panelists speaking on health disparities are Dr. Rupa Marya, author of “Inflamed,” and by Daisy Hernandez, author of “The Kissing Bug.”

The 2022 titled presenters are: Luis J. Rodriguez, the D. Charles Whitney Reader and Cornelius Eady, the Stephen Minot Lecturer. Three recent MFA alumni, Jasmine Elizabeth Smith, Kate Bonnici, and Edgar Gomez will present from their nationally awarded/lauded debut releases.

In addition to readings, discussions, panels, and audience Q&As, guests will also be able to enjoy music by The Cornelius Eady Trio and Rupa & the April Fishes on Feb. 15.

For a complete Writers Week Festival schedule: writersweek.ucr.edu

Meet the 2022 LA Review of Books-UCR Department of Creative Writing Lifetime Achievement Award honorees

Sandra Cisneros

Cisneros is a poet, short story writer, novelist, essayist, performer, artist, and professor. In 2016 President Barack Obama presented her with the 2015 National Medal of Arts Award, the highest honor given to artists and art patrons by the United States government. Cisneros has a long list of accolades, including many for debut novel, “The House on Mango Street.” She is currently residing in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico.

Question: How has the pandemic made you adjust or readjust to the need for human interaction?

Answer: I don’t need much, I’m pretty much of an introvert, like most writers are. I feel guilty at how much I have savored this spiritual retreat. My convent of one, I am surrounded by my little critters: wasps, ants, hummingbirds, the sky is very wide all around me. No me siento sola. I have nice conversations with the ants, leaves, flowers. My dogs are here. I don’t feel solitude. I have neighbors. We talk to each other from the porch, say hello. It’s impossible in Mexico to be absolutely isolated; everyone rings your doorbell— someone looking for work, the gas man, the water guy, a vendor. I buy tortillas from people from the country, empanadas… there is a cooperation here that I like, and I don’t see in the United States… that kind of interaction, even from my second-floor balcony, makes me feel I am part of a community.

There’s a convent near my house, I stop by there too. The madrecitas, the nuns, are praying and I’m doing my writing; God is love, God is your lover, you are the beloved… whether it’s from a tree or your chihuahua, you are connected to all these things. Love is all around.

Q: How does a writer find their voice?

A: Think about what makes you different and write from there. We are all different, even if you are from the same family, culture, etc., you have your own experiences. Think about that, it helps you to narrow it down. Years ago, I went to a program where I felt I was imitating the voices that were in vogue. I had to ask myself, ‘What do I know that nobody else does?’ Ask that question and write from that place.

Also, you have to have tenacity. Talent is not enough. You have to work like a mexicano, like a Mexican. You have to work hard. It’s tenacity, it’s ganas. I tell young writers: you are going to have failures. Life is defined not by your success, but by how you get up from your failures and keep going. That is how you shine and show how great and strong you are. Hang in there!

Q: What question do interviewers never ask you, that you wish they did?

A: About clothes! I’ve been fascinated with textiles since a young age because my father worked with interior designers and brought home scraps of quality textiles from all over the world.

I love fashion, I love how subversive material can be… I love Mexican designers, designers from third world countries, how they make textiles based on their cultures. If I wasn’t a writer, I wish I could be a designer.

To me, it’s important to wear something about your heritage. It can be something that belonged to your family, to your abuela. It helps you be fearless in front of other people — it gives you strength, I always tell women that. Look at our culture and pull strength from that and it’s also an opportunity to educate others.

Linda Hogan

Hogan is an author, poet, Pulitzer finalist, The Chickasaw Nation Writer in Residence, professor, environmentalist, and activist. Her poetry has received many accolades, including the Colorado Book Award, Oklahoma Book Award, an American Book Award, and a prestigious Lannan Fellowship from the Lannan Foundation. She has also received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers Circle of the Americas, among others.

Q: How do your books “come together?” For example, how do you know what group of poems belong in one book?

A: The books don't really come together so much as my life at the time of writing the poetry or novel is in a place where an inner world is coming together. The psyche does her work in the human spirit. That work brings thoughts, feelings, the outer world, my reading, all together into its circle. This is for poetry. The poems soon become all of a whole and if I am fortunate, I see it like it is a puzzle, where pieces fit. So there may be sections. Then one will loop into a chain with the next, one with another. Itisn't planned so much as an event that is happening. It is what I love about the work; it has a mind of its own and if we are open enough, the world walks in and does its job. If I tried to control this world of magic, I would fail at the job because my work is always much more intelligent than I am. In the case of my last book, "A History of Kindness," the ecosystem of place and history have their voice in it, also, and they have to speak. The cosmos also has its story. I am simply the one who cleans up after all the rest. The housekeeper, but with a final say.

Q: What role does religion or spirituality play in your writings?

A: Thank you for noticing. And for noting the difference between religion and spirituality. In my work, whether novels, poetry, or essays, everything in the world around us is known as sacred as it is. This is placed in the writing so that we are all reminded, and the world would never let me get away with less than this reminder. The spirituality comes not only from Indigenous knowledge and understanding of our earth, the plant and animal inhabitants all our equals, and the rest for which we need to be grateful. The Onandaga Thanksgiving prayer speaks for the air, snow, rain, mountains, water, all we need to care for. And this is a found part of all traditions. Sometimes other people simply forget their own traditions are based in the earth knowledge and ecosystem intimacy as much as ours are.

We humans are a symmetry with the rest. We are together in it, all same as the world around us. That is why we cannot damage more of it. Power, the novel, for instance is about toxins in the environment as much as it is about a verdict of guilt or innocence for a shooter. It is about a sick and hungry animal in a ruined ecosystem as much as whether a girl must decide between the American way that created the situation or her own elders who want and need her to pass on tribal knowledge.

Q: Women or female bodies tends to show up in your work. Do women possess a different or unique power to bring about change in communities, the environment, etc.?

A: It is interesting that no one asks men or male writers why they write about men and boys and their bodies, why all the books are inhabited by their gender. Even numerous books by women. But, as a female, I am asked this all the time. My answer is simple and although I grew up in a family of men, I am a woman. I know us, what we are like, what we want and need and desire and suffer. I speak with my friends about the things men don't talk about. Or at least the men I have known. I write about us because it's what I know best and yet my main character in "The People of the Whale" is a man, yet no one notices. Nor do they notice the great men in "Solar Storms," or that main characters in "Mean Spirit" are all men.

No, I don't think we women will change this world on our own or we would have done it already because so many are passionate in beliefs. We will all have to work together to change this very disturbed world, and those men who are so-called patriots and others who would hold to their centuries old ways of being (Civil War era) will try to hold us back, will be gone by the wayside. There is no place for proud boys, we need men who take pride in their work. What do proud boys do in the world to have any pride? There isn't room for them when we have so much of the right kind of work to do. Women may have some better judgment, some better ways of working together, less ego dominance, but we also need the men. So far, we are better at community, at understanding.

In the past we, our tribal nations had clan mothers. Then, with the Europeans and their numerous wars fought on our earth, we had ambassadors, but even now we Chickasaw women set the heartbeat for the dancers. We are the ones who have things moving, but not all the events and happenings. Yet we do still have women in governance and as ambassadors and advisors of others. So, they appear in my poetry. Old Mother is, was, an example of this when she was here, the one who taught me, the one I so love still. I still hear her voice and recall her words, so perhaps she is not gone in that way.

Q: Why is it important to tell the stories of the Chickasaw nation?

A: Of course it is always important to tell what we know and write our own truth. Therefore, it is where and how I am based and grounded. It is what I am.

I have to tell these things because who else is talking about our astronomy, our ancient buildings, our mounds? Only archaeologists and when you think of it, they make their own stories, as do anthropologists and historians. It all seems so up for grabs when it comes to relating meaning to objects, times, wars, and places. You only know what you see, are taught to remember for a teacher, or have a found item. But someone else needs to write what they also know or see.

I put together many sources, including ancient botanists, those who knew the animals, the maps, and I look at them together as if all laid out before me to come to the truth, or the closest to truth that I can find. My work has made this possible. My research and interviews, also. I was fortunate to have time to speak with others, before I worked in Oklahoma, like Tom Phillips, the well-known artist and one of our elders in San Francisco. We are everywhere. He gave me the background in horses and loved that I lived with a Chickasaw pony, had my pictures of her and possibly used them in his own work, as I used his words in my work. Although some have not believed the oral histories, he was always absolutely correct.

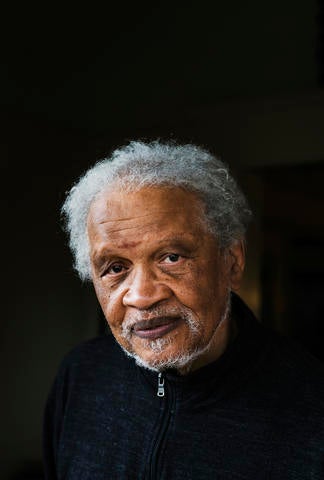

Ishmael Reed

Reed is a satarist, activist, professor, and author of more than 40 books. An article in The New Yorker best describes him: For half a century, he’s been American literature’s most fearless satirist, waging a cultural forever war against the media that spans a dozen novels, nine plays and essay collections, and hundreds of poems. His most recent work is a one-act play, “The Slave Who Loved Caviar,” a satirist look into the relationship between artists Jean-Michel Basquiat an Andy Warhol. His book, "Mumbo Jumbo," cited by literary critic Harold Bloom as one of the five hundred most significant books in the Western canon, celebrates 50 years in circulation in 2022.

Q: You are a satirist, a strong voice here and abroad. How did you find your voice?

A: I didn’t find my voice until I went to New York. As a kid, we had been denied Black history, culture and tradition in schools. In New York City I met pioneers such as Langston Hughes, who was was responsible for my first novel, "The Free-Lance Pallbearers" in 1967. I met many people and very lucky for me, worked for the newspaperman A.J. Smitherman, the hero in the Tulsa riots of 1921. He interrupted lynchings, worked for Native American rights. He was my mentor. I was in my 20s and I helped put out the newspaper; I interviewed Malcolm X in 1962. It was in New York that I met a number of writers who turned me into Black history and Black culture… all of us have to fight to retain our history and culture.

Q: In terms of writing, what does a typical year look like for you?

A: Since I began writing I was able to juggle different forms. The turning point in my career was when I decided I wanted to reach wider audiences. I studied Japanese and eventually published Japanese by Spring, which in 2016 became a national project in China. I also studied Yoruba, a language most African ancestors spoke. That got me a trip to Nigeria.

Also, since March last year I have been contributing to Libération in Paris; El País in Spain published my OpEds on George Floyd. It’s important to reach out to the globe. I also took a look at John Wilkes Booth, his ideals and motivations to kill President Lincoln sound much like today’s Republican platform. This piece was published in Israel, nobody in America would publish it. Here, it is difficult for Black and brown writers to find spaces to publish. The only way we can express ourselves is through plays, novels, and anthologies. Anthologies are acts of defiance… they challenge the establishment.

Q: What question do interviewers never ask you, that you wish they did?

A: I’ll tell you which question I’m always asked: ‘Are you hopeful?’ What does that even mean? Are we talking about the American experiment? A doom-and-gloom scenario? I don’t think they ask white authors that question.