While most of us were baking sourdough bread and watching “Tiger King” to stay sane during the pandemic shutdown, UC Riverside bioengineering professor William Grover kept busy counting the colorful candy sprinkles perched on top of chocolate drops. In the process, he discovered a simple way to prevent pharmaceutical fraud.

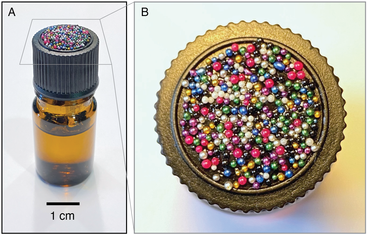

The technique, which he calls CandyCode and uses tiny multicolored candy nonpareils or “hundreds and thousands” as a uniquely identifiable coating for pharmaceutical capsules and pills, is published in Scientific Reports.

Counterfeit or substandard medicines harm millions of people and cost an estimated $200 billion annually. In the developing world, the World Health Organization estimates that one in 10 medical products is fake.

Grover’s lab has previously worked on simple, low-cost ways to ensure the authenticity of pharmaceuticals. Other researchers have been interested in putting unique codes on pills that can be used to verify their authenticity, but all of those schemes have practical limitations.

“The inspiration for this came from the little colorful chocolate candies. Each candy has an average of 92 nonpareils attached randomly, and the nonpareils have eight different colors. I started wondering how many different patterns of colored nonpareils were possible on these candies,” said Grover. “It turns out that the odds of a randomly generated candy pattern ever repeating itself are basically zero, so each of these candies is unique and will never be duplicated by chance.”

This gave Grover the idea that the nonpareils could be applied as a coating to each pill, giving it a unique pattern that could be stored by the manufacturer in a database. Consumers could upload a smartphone photograph of a pill and if its CandyCode matches one in the database, the consumer could be confident that the pill is genuine. If not, it is potentially fraudulent.

To test this idea, Grover used edible cake decorating glue to coat Tylenol capsules with nonpareils and developed an algorithm that converts a photo of a CandyCoded pill into a set of text strings suitable for storing in a computer database and querying by consumers. He used this algorithm to analyze a set of CandyCode photos and found they function as universally unique identifiers, even after subjecting the CandyCoded pills to physical abuse that simulates the wear-and-tear of shipping.

“Using a computer simulation of even larger CandyCode libraries, I found that a company could produce 10^17 CandyCoded pills—enough for 41 million pills for each person on earth—and still be able to uniquely identify each CandyCoded pill,” Grover said.

Even more unique CandyCodes could be created with the introduction of more colors or combining different sizes or shapes of candy nonpareils. CandyCodes could also be used to ensure the authenticity of other products that are often counterfeited. Bottle caps, for example, could be coated with adhesive and dipped in nonpareils to ensure the integrity of perfume or wine and garment or handbag hang tags could be coated with glitter.

CandyCoded capsules or tablets have an unexpected benefit for the consumer as well.

“Anecdotally, I found that CandyCoded caplets were more pleasant to swallow than plain caplets, confirming Mary Poppins’ classic observation about the relationship between sugar and medicine,” said Grover.

The open access paper, “CandyCodes: simple universally unique edible identifiers for confirming the authenticity of pharmaceuticals,” is available here.

Header photo: Chocolate drops covered with candy nonpareils (left), a bowl of colorful candy nonpareils (center), pharmaceutical caplets coated with nonpareils (right). (William Grover)