Tiny, invisible gases long thought to be irrelevant in cloud formation may actually play a major role in determining whether clouds form—and possibly whether it rains.

That’s the surprising finding from a new UC Riverside-led study, which runs counter to more than a century of assumptions about the physics behind cloud droplet formation. Published in the journal Science Advances, the research reveals that removing common trace gases from air samples significantly alters how water vapor condenses into cloud droplets.

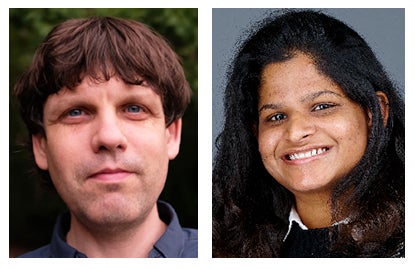

“This was not something we expected to see,” said Markus Petters, a co-author of the study and an atmospheric chemist in UCR’s Bourns College of Engineering. “It turns out that these volatile organic compounds—trace gases—can either help or hinder the ability of tiny particles in the atmosphere to become cloud droplets.”

Clouds begin to form when water vapor rising into cooler air condenses around aerosol particles—tiny bits of salt, dust, or pollution suspended in the air. These particles act as “cloud condensation nuclei,” or CCN. For a droplet to form around a CCN, the air must be supersaturated, meaning it is just over 100% humidity, such as 100.1% or 100.5%, and the threshold of supersaturation depends on the size and chemical makeup of the CCN.

But Petters and UCR doctoral student Elavarasi Ravichandran, who is first author of the study, investigated a third factor—trace gases like organic acids, which exist in the atmosphere at low concentrations. When these gases were removed from test samples using a charcoal-based scrubber, the ability of particles to form droplets changed dramatically.

“What really surprised us was how big the effect was,” Petters said. “The change was comparable to what you’d expect if you heated the particles or exposed them to intense UV radiation for days. But we achieved that effect with just a 20-second treatment to remove the gases.”

The researchers gathered samples from Southern California’s marine cloud layer in La Jolla, near the peak of Mt. Soledad, where moist ocean air mixes with urban air pollution.

“Southern California is one of the most chemically complex places in the country,” Petters said. “We don’t know yet which specific gases are responsible for what we observed, but we suspect compounds like formic or lactic acid could be involved.”

The implications are potentially far-reaching. Cloud behavior influences weather, climate, and the planet’s energy balance. Clouds reflect sunlight, cool the Earth’s surface, and—in the right conditions—release rain. Yet, even after decades of climate modeling, predicting exactly when and how clouds form remains one of science’s biggest challenges.

This study suggests researchers may have overlooked a key piece of the puzzle.

“If you asked someone five years ago, they’d say the gas phase likely doesn’t matter for cloud formation,” Petters said. “Now we know that’s not entirely true. There’s something happening at the air-water interface that we don’t fully understand yet.”

Even more perplexing, the gases didn’t behave as theory would predict. In some cases, instead of promoting droplet formation—as would be expected if the gases lowered surface tension—they appeared to suppress it.

“That was the second surprise,” Petters said. “The gases had the opposite effect of what thermodynamic models would suggest. It means we need to go back and re-examine the basic physics of how particles and gases interact at the microscopic level.”

Petters emphasized that the team has not yet identified the exact mechanism behind the effect, or the full range of compounds involved. But the findings are already prompting new questions—and new avenues of research.

“This opens up a whole new pathway to explore,” Petters said. “We’ve raised a flag that trace gases matter. Now we need to figure out when, where, and why—and what that means for cloud systems around the world.”

The paper’s title is “Removal of Trace Gases Can Both Increase and Decrease Cloud Droplet Formation.” Its findings come from a larger research collaborative in San Diego called the Eastern Pacific Cloud Aerosol Precipitation Experiment (EPCAPE), led by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) division with participating scientists from UCR and UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Petters and Ravichandran are with UCR’s College of Engineering – Center for Environmental Research and Technology, or CE-CERT, which is focused on research about air pollution, emissions testing, renewable energy, and intelligent transportation systems, among other work to advance cleaner, more healthful, and more efficient technologies.