Scientists have identified a promising new way to detect life on faraway planets, hinging on worlds that look nothing like Earth and gases rarely considered in the search for extraterrestrials.

In a new Astrophysical Journal Letters paper, researchers from the University of California, Riverside, describe these gases, which could be detected in the atmospheres of exoplanets — planets outside our solar system — with the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST.

Called methyl halides, the gases comprise a methyl group, which bears a carbon and three hydrogen atoms, attached to a halogen atom such as chlorine or bromine. They’re primarily produced on Earth by bacteria, marine algae, fungi, and some plants.

One key aspect of searching for methyl halides is that exoplanets resembling Earth are too small and dim to be seen with JWST, the largest telescope currently in space.

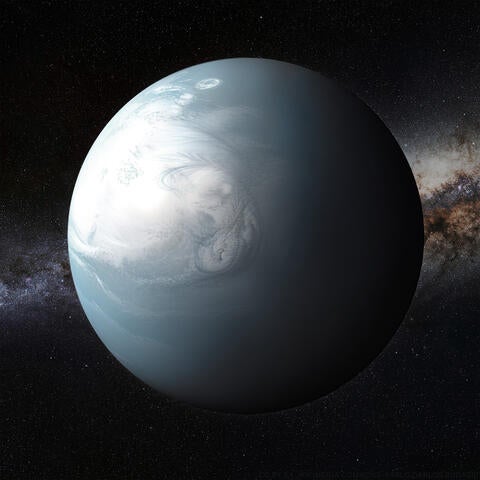

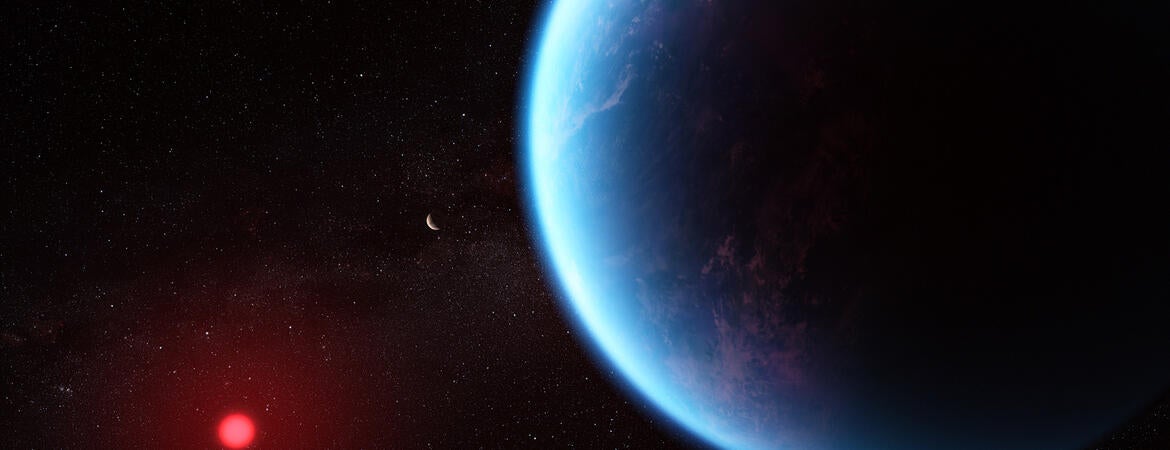

Instead, JWST would have to aim for larger exoplanets orbiting small red stars, with deep global oceans and thick hydrogen atmospheres called Hycean planets. Humans could not breathe or survive on these worlds, but certain microbes might thrive in such environments.

“Unlike an Earth-like planet, where atmospheric noise and telescope limitations make it difficult to detect biosignatures, Hycean planets offer a much clearer signal,” said Eddie Schwieterman, UCR astrobiologist and paper co-author.

The researchers believe that looking for methyl halides on Hycean worlds is an optimal strategy for the present moment in time.

“Oxygen is currently difficult or impossible to detect on an Earth-like planet. However, methyl halides on Hycean worlds offer a unique opportunity for detection with existing technology,” said Michaela Leung, UCR planetary scientist and first author of the paper.

Additionally, finding these gases could be easier than looking for other types of biosignature gases indicative of life.

“One of the great benefits of looking for methyl halides is you could potentially find them in as few as 13 hours with James Webb. That is similar or lower, by a lot, to how much telescope time you’d need to find gases like oxygen or methane,” Leung said. “Less time with the telescope means it’s less expensive.”

Though life forms do produce methyl halides on Earth, the gas is found in low concentrations in our atmosphere. Because Hycean planets have such a different atmospheric makeup and are orbiting a different kind of star, the gases could accumulate in their atmospheres and be detectable from light-years away.

“These microbes, if we found them, would be anaerobic. They’d be adapted to a very different type of environment, and we can’t really conceive of what that looks like, except to say that these gases are a plausible output from their metabolism,” Schwieterman said.

The study builds on previous research investigating different biosignature gases, including dimethyl sulfide, another potential sign of life. However, methyl halides appear particularly promising because of their strong absorption features in infrared light as well as their potential for high accumulation in a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere.

While James Webb is currently the best tool for this search, future telescopes, like the proposed European LIFE mission, could make detecting these gases even easier. If LIFE launches in the 2040s as proposed, it could confirm the presence of these biosignatures in less than a day.

“If we start finding methyl halides on multiple planets, it would suggest that microbial life is common across the universe,” Leung said. “That would reshape our understanding of life’s distribution and the processes that lead to the origins of life.”

Moving forward, the researchers plan to expand this work on other planetary types and other gases. For example, they’ve done measurements of gases emanating from the Salton Sea, which appears to produce halogenated gases, such as chloroform. “We want to get measurements of other things produced in extreme environments on Earth, which could be more common elsewhere,” Schwieterman said.

Even as researchers push the boundaries of detection, they acknowledge that direct sampling of exoplanet atmospheres remains beyond current capabilities. However, advances in telescope technology and exoplanet research could one day bring us closer to answering one of humanity’s biggest questions: Are we alone?

“Humans are not going to visit an exoplanet anytime soon,” Schwieterman said. “But knowing where to look, and what to look for, could be the first step in finding life beyond Earth.”

(Cover image: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted/STScI)